Dazzling, shimmer curtains of red and green… you’ve probably seen amazing photos of the aurora, or northern lights. Unfortunately, if you’re lucky enough to see the aurora with your own eyes, it typically won’t live up to those expectations.

Technology and biology are why.

For those of us in the mid-latitudes–that is, most of the U.S.–aurora aren’t visible very often, especially the farther south you are. And when they do show up, they’re typically not very bright.

So how do photographers snap such stunning photos?

“Cameras with long exposures will pick up on the northern lights because cameras use that long exposure of several seconds to absorb the light and colors of the aurora,” says Willard Sharp, who photographs everything from severe storms to solar storms. “Modern camera sensors are very sensitive in low light, so it’s easier to get a detailed photo of the aurora.”

A long exposure and wide-open aperture let a lot of light in. “This allows the camera to gather data in a photo that I can then work with in Adobe Lightroom or Photoshop to bring out details and get the colors to look good and natural,” Sharp says.

“Your eyes may not catch as much color here [in the Lower 48], but the camera will do a wonderful job with that several second exposure to get a vivid picture.”

And why won’t your eyes catch much color? As great as they are, they’re just not equipped to do color at night.

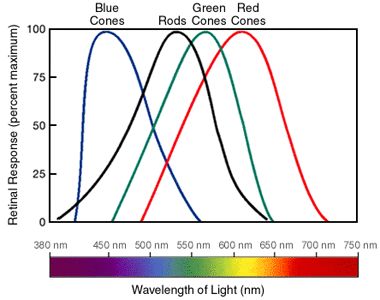

You might know that your eyes have rods and cones, which are stimulated by light. The gist is that we have three types of cones that work with the brain to see red, green and blue (and all the combinations of those), but cones need a lot of light... something that the night sky doesn’t provide.

Rods are much more sensitive to light so we can see at night, but they don’t have nearly the same color abilities as cones. Sure, we can kind of see color, but it’s not at all vivid. Our eyes, like a camera, need a wide aperture and a lot of light to get the most out of what’s in front of us.

Even so, “when you head north to, say, Canada, the lights are much brighter even with weaker geomagnetic storming, so the eyes can see them much more easily,” Sharp says.

Sharp has a “night skies cheat sheet,” if you’re interested in trying out astrophotography. And you’ll need patience. Forecasting space weather is even more difficult than Earth weather forecasts, and Sharp says looking at the data can be “daunting.”

“Sometimes a predicted geomagnetic storm will not pan out as expected. Other times minor space weather events trigger big and bright aurora displays,” says Sharp.

NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center has an aurora dashboard that displays current space weather conditions and aurora forecasts. Sharp also recommends SpaceWeatherLive. Here are the parameters he likes to see:

- Kp: At least 5

- Bz: At least -10 for at least one hour; two or more hours is better, and -20 suggests aurora visible to the naked eye

- Solar winds: At least 500 km/sec

- Density: At least 5, but 10 or higher is better

Wondering how northern lights even happen in the first place? We have the answer. Plus, your chances of seeing amazing aurora photos–or maybe with your own eyes–could be increasing, as solar activity is forecast to peak in 2024.

Our team of meteorologists dives deep into the science of weather and breaks down timely weather data and information. To view more weather and climate stories, check out our weather blogs section.