BANGASSOU, Central African Republic (AP) — Monique Moukidje fled her home in Central African Republic’s town of Bangassou in January when rebels attacked with heavy weapons, the fighting killing more than a dozen people.

“I ran away because the bullets have no eyes,” the 34-year-old said sitting in the shade while waiting for water purification tablets, a tarp, and other supplies to help her in Mbangui-Ngoro, a village where she and hundreds of other displaced people are sheltering.

She is among an estimated 240,000 people displaced in the country since mid-December, according to U.N. relief workers, when rebels calling themselves the Coalition of Patriots for Change launched attacks, first to disrupt the Dec. 27 elections and then to destabilize the newly-elected government of President Faustin Archange Touadera. The rebels’ fighting has enveloped the country and caused a humanitarian crisis in the already unstable nation.

Hundreds of thousands of people are also left without basic food or health care, and with the main roads between Central African Republic and Cameroon closed for almost two months, prices have skyrocketed leaving families unable to afford food.

The rebels control nearly two-thirds of the country, making it difficult to deliver humanitarian aid. Aid delivery was stopped for nearly a month in some zones.

“The most pressing needs are on the axis (the main roads),” says Marco Doneda, project coordinator for Doctors Without Borders based in Bangassou, on the country’s southeastern border with Congo.

When rebels left Bangassou in mid-January, after an ultimatum from the United Nations peacekeeping force, some established their bases in nearby towns, like in Niakari, about 17 kilometers (10 miles) from Bangassou. Doctors Without Borders has been trying to reach the populations there with mobile clinics since then, but they have been prevented by the possibility of military action or unpredictable fighting between the rebels and the army.

Along the main supply road from Cameroon to Bangui, Central African Republic’s capital, and in Bambari and Bossangoa, the government forces and its Rwandan and Russian allies have led drives against the rebel forces in the past two weeks.

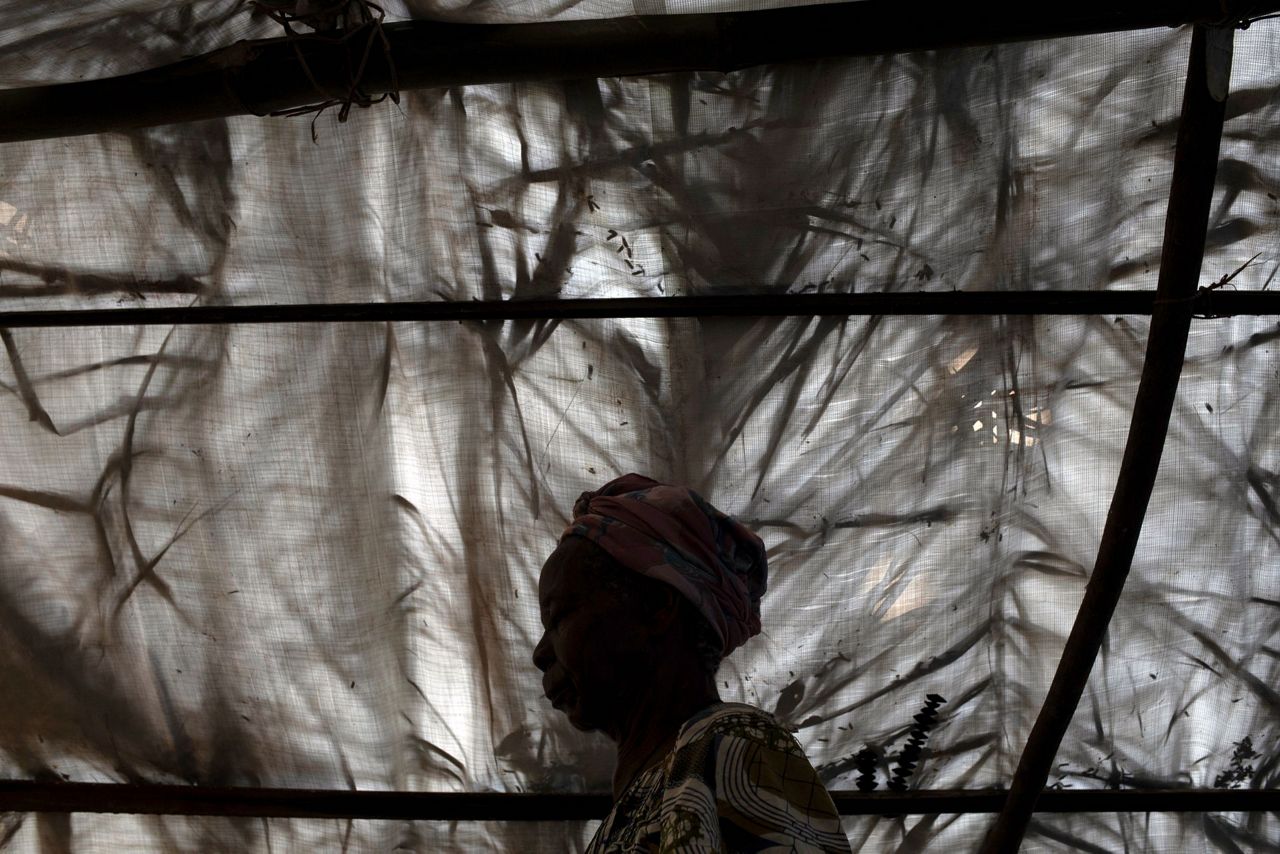

The impact of violence and the lack of humanitarian access is visible in Siwa, a camp for internally displaced people, a few kilometers (miles) from Bangassou.

Hundreds of people must rely only on filthy brown water to drink, cook, and clean. They are living in makeshift shelters made of leaves and branches from palm trees. No toilets have been built and food distribution only arrived six weeks after the camp was created.

A displaced man hopes his wife will receive treatment and psychological support after she was raped by armed men.

“I didn’t have the strength to defend my wife,” he said. “I’m a farmer. I don’t have the means to bring her to Bangassou for treatment, but I’m worried, I can’t leave her like this. Her body is not wounded, but in her mind, she is not all right.” The Associated Press does not name victims of sexual violence.

Central African Republic’s instability erupted into fighting in Bangui in 2013 when the Seleka rebels coming from the north seized power from then-President Francois Bozize.

Later that year, the Seleka government was challenged by a militia group that formed in response and called themselves the anti-Balaka. Fighting spiraled, with targeted attacks that left thousands dead in the capital and displaced hundreds of thousands more.

The newly formed rebel coalition includes armed groups from both the ex-Seleka and anti-Balaka.

The Seleka rebel president eventually stepped aside amid international pressure and an interim government organized democratic elections in 2016, which Touadera won.

Touadera won re-election to a second term in December with 53% of the vote, but he continues to face opposition from forces linked to ex-president Bozize, who was disqualified from taking part in the presidential vote. Much of the recent violence began after the courts rejected his candidacy before the Dec. 27 elections.

Residents of Central African Republic are discouraged by the country’s years of violence and insecurity.

“We really moved backward,” said Pierrette Benguere, prefect of the Mbomou area that includes Bangassou. “It is discouraging to see my country having to start over again with the negotiations we’ve been holding on and off since 2003.”

Copyright 2021 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.