Hurricane landfall, as with real estate, is all about location, location, location. However, the definition of “landfall” can be more technical than practical.

In the early morning hours of Oct. 8, 2016, Hurricane Matthew battered Hilton Head Island, South Carolina.

It downed more than 100,000 trees, damaged nearly 3,000 structures and knocked out power for days.

But at that point, the hurricane still hadn’t made landfall in the U.S. In fact, it would only barely do so later that morning, staying just miles off the Southeast coast most of the time it slammed parts of the region with wind and water (also as “only” a Category 1 hurricane).

The National Hurricane Center (NHC) says that landfall happens at “the intersection of the surface center of a tropical cyclone with the coastline.” In other words, it happens when the middle of the storm’s circulation crosses land.

That means that a hurricane’s eyewall could come ashore but not technically make landfall if the storm’s center doesn’t actually meet the coastline.

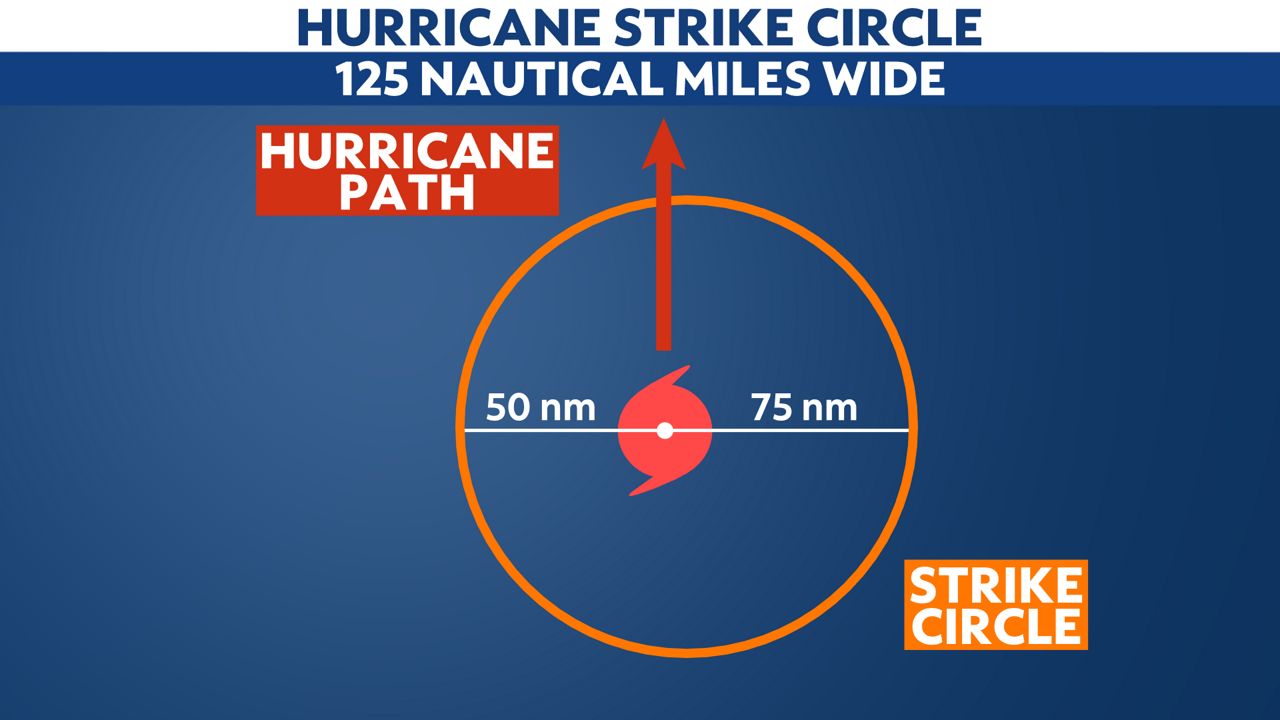

The NHC has a definition for a hurricane “strike,” too. That happens if a location is within the strike circle, an imaginary circle 125 nautical miles wide that’s centered just to the right of a hurricane’s center.

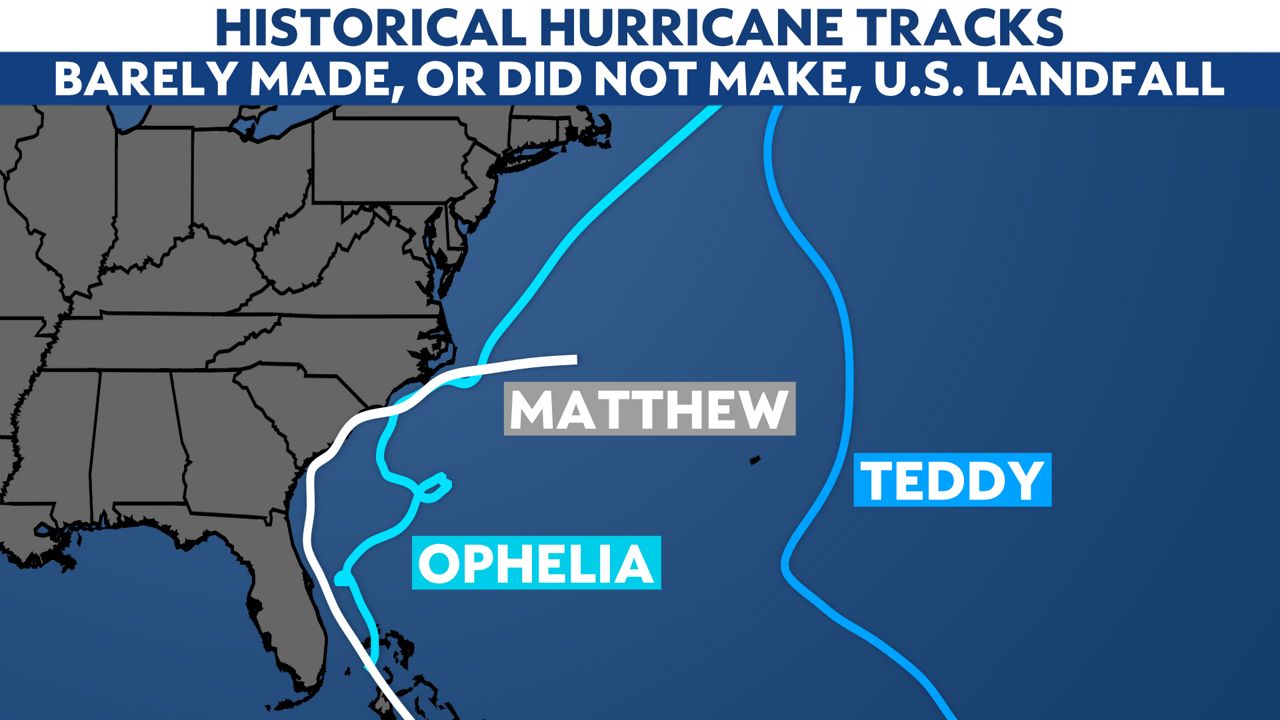

Hurricane Matthew did finally (barely) have a U.S. landfall after scraping the Florida and South Carolina coast. It didn’t take long for the center to move back offshore, when it brought a foot of rain and devastating flooding to parts of North Carolina.

Two hurricanes in recent memory had noteworthy impacts in the U.S. despite not making landfall on our shores: Ophelia in 2005 and Teddy in 2020.

2005’s Hurricane Ophelia meandered up the Southeast U.S. coast, including wandering along the shore of North Carolina for three days.

Winds were strongest near the ocean, but the biggest issues came from the water, both from flooding and beach erosion. Ophelia damaged hundreds of homes and structures.

Hurricane Teddy was hundreds of miles from the East Coast in Sept. 2020, but it was a potent and very large storm; tropical storm-force winds stretched 850 miles wide at one point.

While it brought gusty winds to some coastal areas in New England, the biggest effects were from high surf and coastal flooding.

Charleston, South Carolina’s high tides reached major flood stage three days in a row, the first time on record. Waves washed away dozens of dunes at Cape Hatteras National Seashore and waves pounded the coast as far north as Maine.

The effects of a hurricane can spread far and wide, whether or not it makes landfall. Even hurricanes that aren’t as big as Teddy was can create dangerous rip currents on the East Coast, even when lurking well out to sea.

Justin Gehrts - Senior Weather Producer

Justin Gehrts is a senior weather producer for Spectrum News. He has well over a decade of experience forecasting and communicating weather information. Gehrts began his career in 2008 and has been recognized as a Certified Broadcast Meteorologist by the American Meteorological Society since 2010.