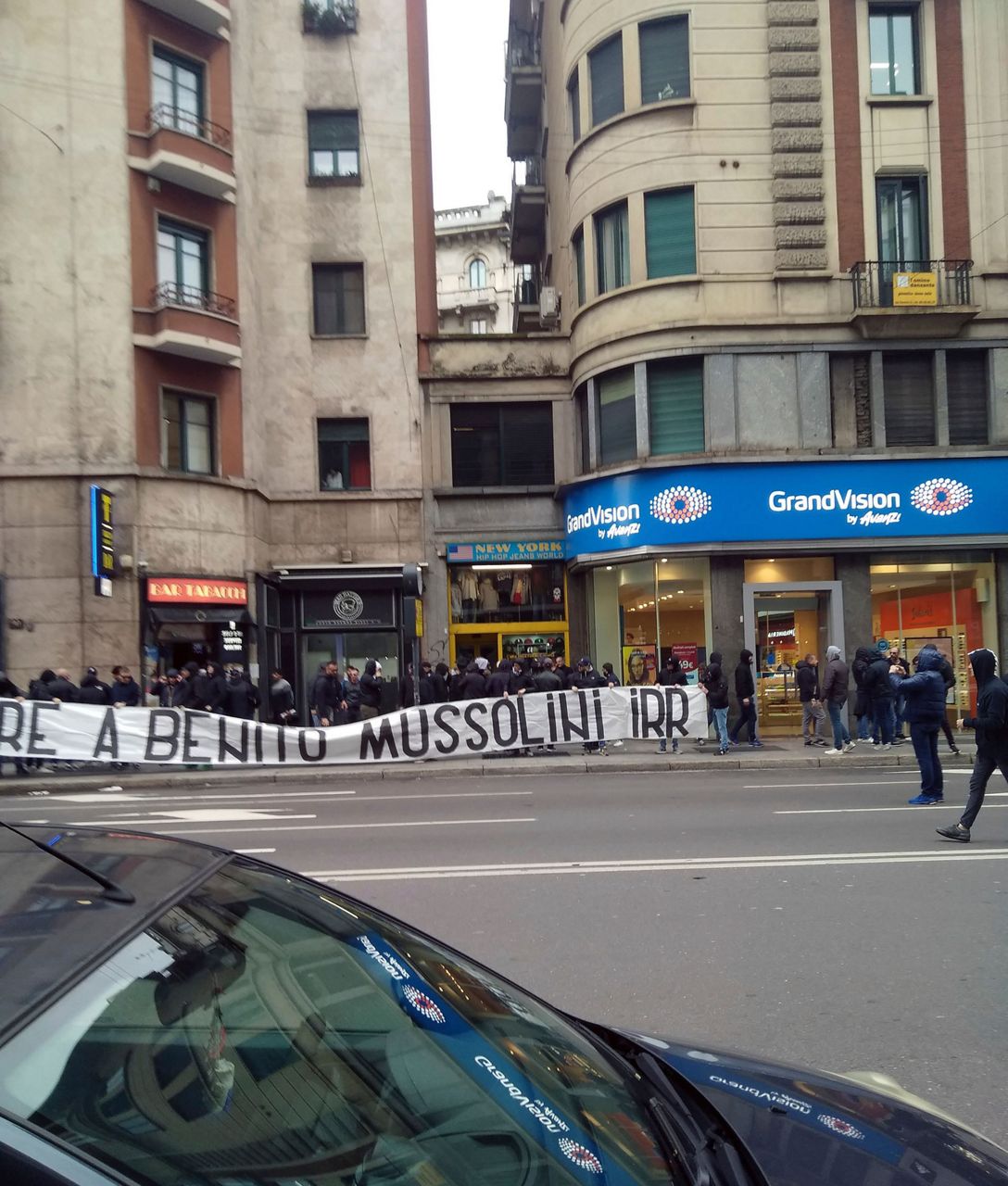

MILAN (AP) — "Honor to Mussolini" read the banner unfurled steps away from the Milan piazza where the Fascist dictator's body was hung upside down in 1945 by partisans after his summary execution. That this was the eve of the 74th anniversary of Italy's liberation from Nazi-fascism was not lost on the leader of the group of soccer hooligans with the banner as he gave the straight-armed fascist salute.

The next day, Italy's president, premier and defense minister attended April 25 Liberation Day commemorations in the capital. But hard-line interior minister Matteo Salvini, the xenophobic, euroskeptic political leader many believe can unite Europe's populist right, stayed away, a move that critics said gave a strong signal to far-right sympathizers ahead of European elections.

Not since Benito Mussolini's ignominious fall after failed attempts at making Italy a colonial power that gave Hitler the upper hand in their axis, has the executed former dictator's image carried such currency.

The perception is growing among Italians that fascism, officially banned as a political movement in Italy but never really vanquished from popular culture or the political fringe, is rearing its head in alarming ways.

Fascist salutes, long a public taboo, have made their way out of the hooligan sections of soccer stadiums and into city streets, as demonstrated by a couple of dozen of the Roman football squad Lazio's historically right-wing and fascist "ultra" fans on visitors' turf in Milan. Fringe far-right political parties are emboldened to shout fascist slogans and raise one-armed salutes in protests against placing Roma families — a minority persecuted in World War II — in Rome public housing. A publishing house tied to the far-right group Casapound was evicted from the prestigious Turin book fair following protests, including from the Auschwitz Holocaust Memorial which threatened to boycott the event.

The SWG polling agency says 71% of Italians believe it is important to combat the return of Nazi and Fascist ideology in Italy, up from 65% just two years ago. Two-thirds believe it is important to repress those who incite fascism, up from 60% in 2017.

"In reality, the entire history of fascism is a problem that remains open in Italy because we have never examined ourselves on what this history says about us, something Italians do not want to do," said Guido Caldiron, a right-wing expert.

Italy never went through a period like Germany's de-Nazification. Mussolini was in power for nearly two decades before Italy entered World War II, a period of modernization during which the fascist regime built schools, railroad stations and administrative buildings that remain in public use today. While his government fell under allied advances in 1943, Mussolini himself was whisked away by the Germans and set up the puppet Salo Republic in Nazi-occupied northern Italy. The move split Italy in half, plunging the country into a civil war that lasted nearly two years with Italian partisans attacking Nazi-fascists in the north.

The mid-war changing of allegiances created a confused post-war legacy of having sided with both the vanquished and the victors that Italy has never fully confronted. Ridding the countryside of fascist symbols so integral to public life was impractical. And the new post-war threat to democracy became communism. Apologism for fascism was criminalized, but neo-fascists were a tolerated part of the political landscape.

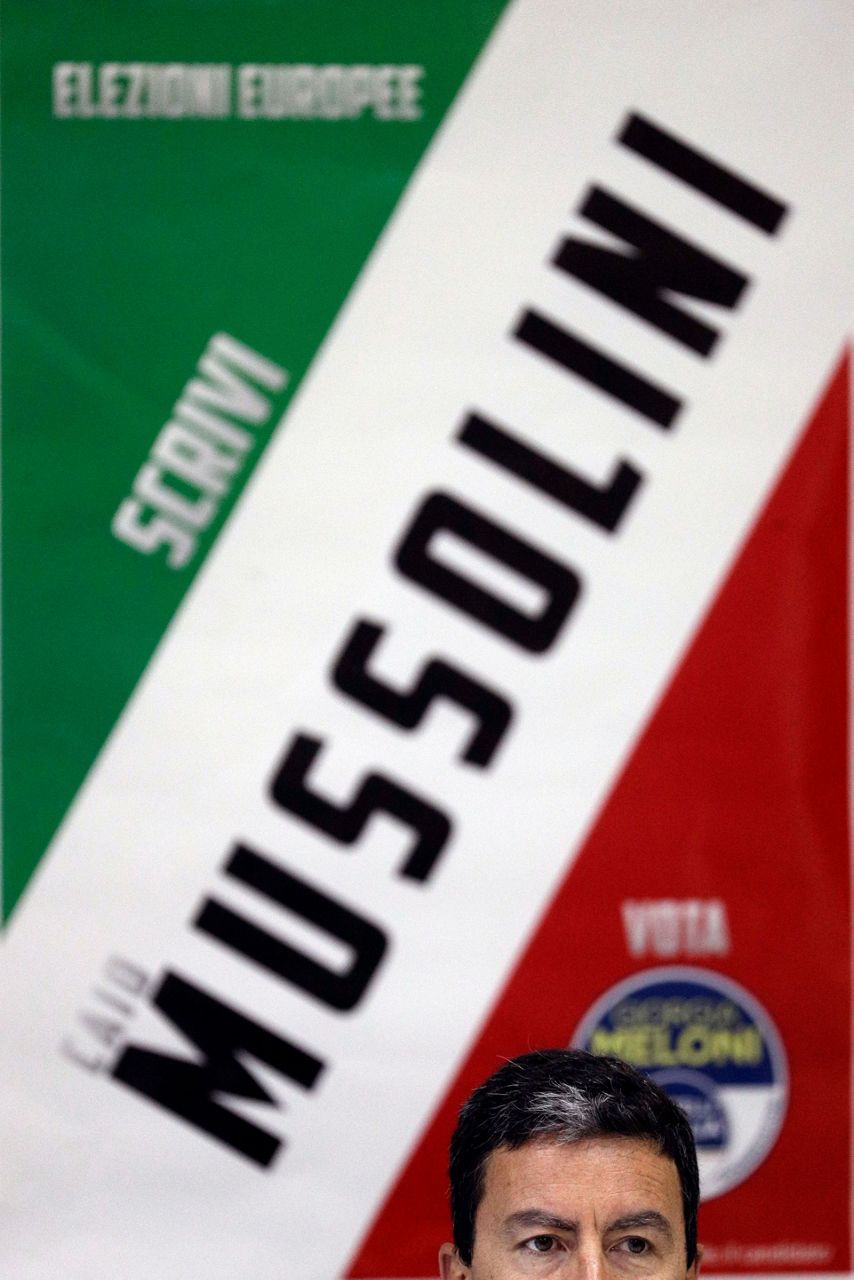

Mussolini's name remains part of the political discourse, first with lawmaker Alessandra Mussolini, Benito Mussolini's granddaughter who started out with a now defunct neo-fascist party, and now with her cousin, who carries the name of two dictators separated by 2,000 years — Caio Giulio Cesare Mussolini — who is running with the far-right Brothers of Italy party in the European elections. Many commentators dismiss his candidacy as a publicity stunt. Mussolini himself has urged people in his district to write in his name, a clear nostalgia ploy to those who want to vote for the name and not just the party, Brothers of Italy.

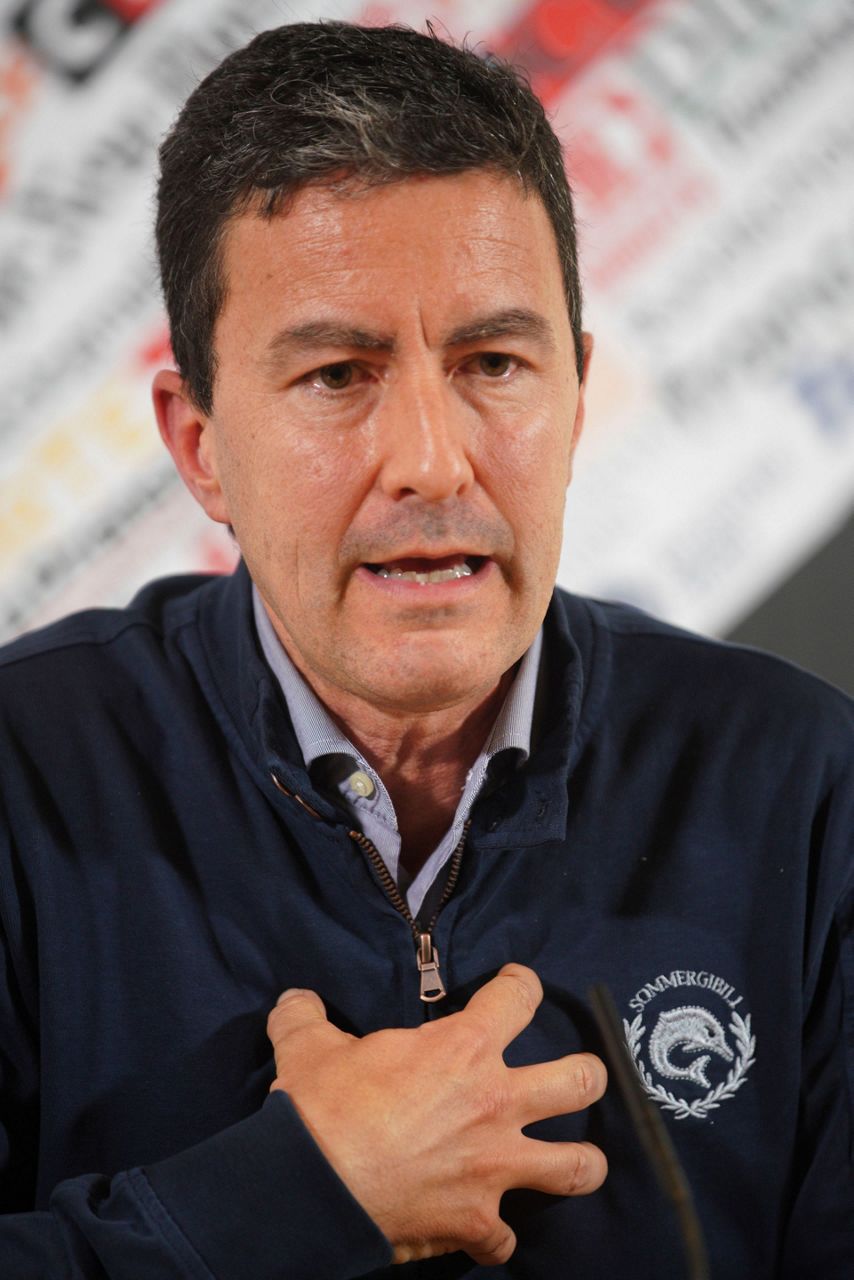

"I continue to meet people from that period who have memories that are more than satisfying," Mussolini told The Associated Press in a recent interview. "I met a 95-year-old person who had a version of that period very different from the one you find in public opinion."

The lack of historical confrontation has permitted a vein that focuses on Mussolini's pre-war achievements: narratives that the trains ran on time, malarial swamps were drained and doors could be left unlocked. Still, Italian's self-image as "brava gente," or "good people," belies Mussolini's 1938 racial laws that declared Jews to be an inferior race. Eight thousand Italian Jews were deported to Nazi death camps, where most perished.

"We know in reality that the regime was full of corruption and criminals, it just doesn't get told," Caldiron said.

Despite the emergence of fascist symbols and rhetoric in this year's European election campaign, political analysts said any conflation of a fascist threat in Italy is an exaggeration.

"There are unpleasant things happening in Italy. Xenophobia is rising, also because of the migrants. But all told there is no danger of fascism. The neo-fascist parties are very small: 1%,'" said Giuseppe Orsina, director of the school of government at Rome's LUISS University.

Still, Salvini's wink at the far-right goes beyond Italy's borders, to far-right leaders in Germany, Italy and Hungary he hopes to unite in a single parliamentary group following this month's European elections.

"Our goal is to change Europe, to become the first group in the European Parliament," Salvini said. "For the first time we could be decisive to change Europe. That's what I care about."

___

Paolo Santalucia and Fanuel Morelli contributed from Rome.

Copyright 2019 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.