CLIMAX, N.C. (AP) — North Carolina is the latest state considering a ban on smokable hemp, a product that's exploding along with the health craze surrounding a compound in the plant known as CBD.

Besides federal regulations laid out in the Hemp Farming Act of 2018, the Food and Drug Administration has no additional regulations on smokable hemp, leaving states to figure out how to govern it themselves.

This year, Indiana, Louisiana and Texas banned smokable hemp entirely, while Kansas banned products including hemp cigarettes and cigars. Tennessee prohibited smokable hemp sales to minors.

North Carolina's House is considering a smokable hemp ban after it recently passed the state Senate.

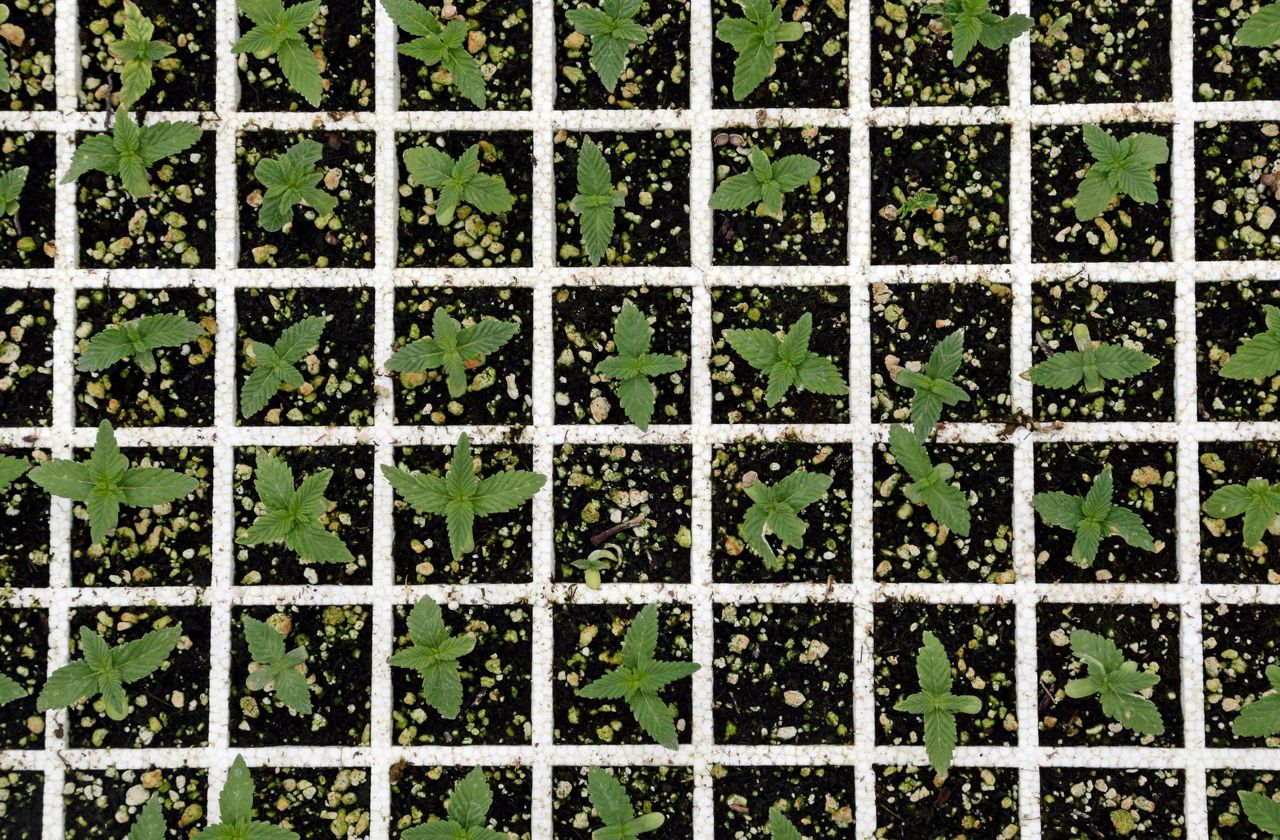

The legislation focuses primarily on expanding the state's pilot hemp growing program, which has more than 1,000 licensed hemp growers and 600 registered hemp processors, to position it as a leader in the burgeoning industry. The bill would place more regulations on hemp but also create a hemp licensing commission and establish a fund for regulation, testing and marketing.

North Carolina law enforcement wants the ban, saying officers have no way of distinguishing smokable hemp from marijuana.

Hemp and marijuana are both cannabis plants. Dried, smokable hemp looks and smells the same as marijuana but contains less than 0.3% of tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC, the compound that gives marijuana its high. Hemp has cannabidiol, or CBD, which many believe helps with pain, anxiety and inflammation, though there's limited scientific research to support those claims. It's turning up in products ranging from lotions and cosmetics to diet pills and juices.

The proposed ban would impose a civil penalty of up to $2,500 for anyone who manufactures, sells or possesses smokable hemp.

But scores of farmers in the traditional tobacco state have told lawmakers a ban would hurt them as many deal with hurricane damage and decreased tobacco prices.

Three years ago, Shane Whitaker grew 275 acres of tobacco on his farm in Climax. This year, the second-generation tobacco farmer planted only 75 acres of his former cash crop and decided to grow hemp.

"We're hoping for a lot of this hemp to replace tobacco," he said. "I'm not for taking part of it off the market."

So far, he said that hemp has been a good source of revenue to keep his farm running.

Second-year hemp farmer Lori Lacy, who has invested more than $190,000 on her 13-acre Franklin hemp farm, said she can make $1,000 for a pound of smokable hemp flower.

"I don't want our infrastructure and everything that we have built up to this point to go away," Lacy told lawmakers at a May hearing. "I will have to fire people."

Smokable hemp is lucrative partly because farmers just need to dry the hemp flowers. Other products require a complicated, costly process for extracting CBD oil.

Jamie Schau, who analyzes CBD markets for the research firm Brightfield Group, said the market for smokable hemp flower is projected to grow to $70.6 million in 2019, up from $11.7 million in 2018. However, she said stigmas around smoking help keep smokable hemp at only about 1.4 percent of the overall market.

Smokable hemp is especially popular in the South, where no states have legalized recreational marijuana and many haven't legalized medicinal marijuana, said Eric Steenstra, president of advocacy group Vote Hemp. Still, its popularity has been a surprise, he said: "Nobody really anticipated that anybody would want to smoke (hemp)."

North Carolina's Senate voted to delay the ban until December 2020 to allow more time to figure out regulation, but a House committee subsequently moved the date a year sooner. That version is continuing to move through the House.

Bill co-sponsor Republican Sen. Brent Jackson of Sampson County prefers the later effective date because he thinks portable tests will be available soon to differentiate hemp from marijuana.

The State Bureau of Investigation and the North Carolina Association Chiefs of Police say delaying the ban would be a "de facto" legalization of marijuana, since people could disguise marijuana as hemp.

Last month, police in Four Oaks charged Amanda Furstonberg, 32, with marijuana possession after they saw her smoking what she says was hemp.

"They had me in tears," she said.

Furstonberg started smoking hemp after a February car accident left her with chronic back pain. To avoid opioids, she tried taking CBD-infused gummies as a pain reliever but wanted something stronger and turned to smokable hemp.

"Within three and five seconds of being able to smoke it, I could tell that my body was starting to feel so much better —the throbbing was going away," she said.

Police Chief Stephen Anderson defended his officers, saying he believed Furstonberg disguised marijuana as hemp. Her case is pending.

For now, farmers continue to grow smokable hemp. This year, Whitaker will plant roughly 30 acres of organic hemp with about 2,400 plants per acre, along with another 800 in a greenhouse.

Driving past empty greenhouses that once held tobacco, Whitaker said farming requires adapting to constant changes.

"It's the Wild West right now," Whitaker said.

Copyright 2019 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.