By itself, being able to read smartphone home screens in Cherokee won’t be enough to safeguard the Indigenous language, endangered after a long history of erasure. But it might be a step toward immersing younger tribal citizens in the language spoken by a dwindling number of their elders.

That's the hope of Principal Chief Richard Sneed of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, who's counting on more inclusive consumer technology — and the involvement of a major tech company — to help out.

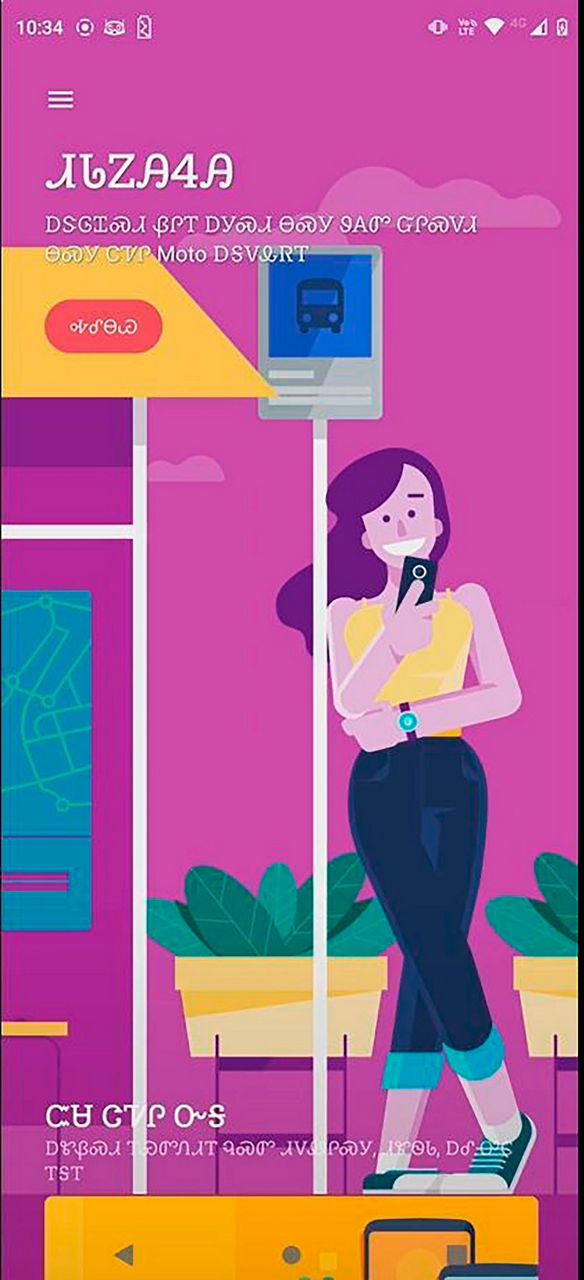

Sneed and other Cherokee leaders have spent several months consulting with Lenovo-owned Motorola, which last week introduced a Cherokee language interface on its newest line of phones. Now phone users will be able to find apps and toggle settings using the syllable-based written form of the language first created by the Cherokee Nation’s Sequoyah in the early 1800s. It will appear on the company's high-end Edge Plus phones when they go on sale in the spring.

“It’s just one more piece of a very large puzzle of trying to preserve and proliferate the language,” said Sneed, who worked with members of his own western North Carolina tribe and other Cherokee leaders who speak a different dialect in Oklahoma that is more widely spoken but also endangered.

It’s not the first time consumer technology has embraced the language, as Apple, Microsoft and Google already enable people to configure their laptops and phones so that they can type in Cherokee. But the Cherokee language preservationists who worked on the Motorola project said they tried to imbue it with the culture — not just the written symbols — they are trying to protect.

Take the start button on the Motorola interface, which features a Cherokee word that translates into English as “just start.” That's a clever nod to the casual way Cherokee elders might use the phrase, said Benjamin Frey, a member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“It could have said ‘let’s get started’ in many different ways,” Frey said. “But it said ‘halenagwu' — just start. And that’s very Cherokee. I can kind of see an elder kind of shrugging and saying, ‘Well, I guess let’s do it.’ ... It reminds me very fondly of how the elders talk, which is pretty exciting.”

When Motorola thought of incorporating Cherokee into its phones, Frey was one of the people it reached out to. It was looking to incorporate a language that the U.N.'s culture agency, UNESCO, had designated as among the world's most endangered but also one that had an active community of language scholars it could consult.

“We work with the people, not about the people,” said Juliana Rebelatto, who holds the role of head linguist and globalization manager for Motorola's mobile division. “We didn’t want to work on the language without them.”

Motorola modeled its Cherokee project on a similar Indigenous language revitalization project Rebelatto helped work on in Brazil, where the brand — part of China-based parent company Lenovo — has a higher market share than it does in the U.S. The company last year introduced phone interfaces serving the Kaingang community of southern Brazil, and the Nheengatu community of the Amazonian regions of Brazil and neighboring countries.

Several big tech companies have expressed interest in recent years in making their technology work better for endangered Indigenous languages, more to show their good will or advance speech recognition research than to fulfill a business imperative.

Microsoft’s text translation service recently added Inuinnaqtun and Inuktitut, spoken in the Canadian Arctic, and grassroots artificial intelligence researchers are doing similar projects throughout the Americas and beyond. But there’s a long way to go before digital voice assistants understand these languages as well as they do English — and for some languages the time is running out.

Frey and Sneed said they recognize that some Cherokee will have concerns about tech companies making a product feature of their work to preserve their language — whether it's a text-based interface like Motorola's or potential future projects that could record speech to build a voice assistant or real-time translator.

“I think it is a danger that companies could take this kind of material and take advantage of it, selling it without sharing the proceeds with community members,” Frey said. “Personally, I decided that the potential benefit was worth the risk, and I’m hoping that that will be borne out.”

Frey didn’t grow up speaking Cherokee, largely due to his grandmother’s experiences of being punished for speaking the language when she was sent to boarding school. For over 150 years, Indigenous children in the U.S. and Canada were taken from their communities and forced into boarding schools that focused on assimilation.

She and others of her generation were beaten for speaking the language, had her mouth washed out with soap and was told that “English was the only way to get ahead in the world,” Frey said. She didn’t pass it on to Frey’s mom.

“This was a 13,000-year chain of intergenerational transfer of a language from parents to children that was broken because the federal government decided that English was the only language that was worthwhile,” he said.

Only about 225 of the roughly 16,000 members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians spoke Cherokee fluently as their first language at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Now I think we’re down to 172 or so,” said Sneed, the principal chief. “So we’ve lost quite a few in the last couple of years.”

The Oklahoma-based Cherokee Nation has more speakers — an estimated 2,000 —- but they are still a fraction of the more than 400,000 people who comprise what is the largest of the 574 federally recognized tribes in the U.S.

Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. said in a statement Monday that incorporating the language into technology products is "a win not just for Cherokee Language preservation, but for the perpetuation of all Native languages.”

Frey hopes the new tool will be a conversation-starter between older Cherokee language speakers and their tech-savvy grandkids. It complements language immersion programs and other homegrown activism that's already happening in North Carolina and Oklahoma. He said it will take more than text-based smartphone interfaces to really make a difference.

“If the youth today are watching TikTok videos, we need more TikTok videos in Cherokee," said Frey. “If they’re paying attention to YouTube, we need more YouTubers creating content in Cherokee. If they’re trading memes online, we need more memes that are written in Cherokee.”

“We do have to make sure that the language continues to be used and continues to be spoken,” said Frey. “Otherwise, it could die out.”

——

AP writer Felicia Fonseca contributed to this report from Flagstaff, Arizona.

Copyright 2022 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.