BUENOS AIRES (AP) — María Eva Noble says she is carrying out the legacy of her namesake as she labors in a soup kitchen in a working class neighborhood of Buenos Aires.

She was named after iconic Argentine former first lady María Eva Duarte de Perón, better known as Eva Perón, or Evita, who died 70 years ago Tuesday. The soup kitchen where Noble does volunteer duty in the Flores district gives daily lunches to about 200 people and is run by an organization that also carries the name of the late leader.

Though not related to Eva Perón, Noble says, “I carry Evita in my DNA.” And she is hardly the only one who feels this way.

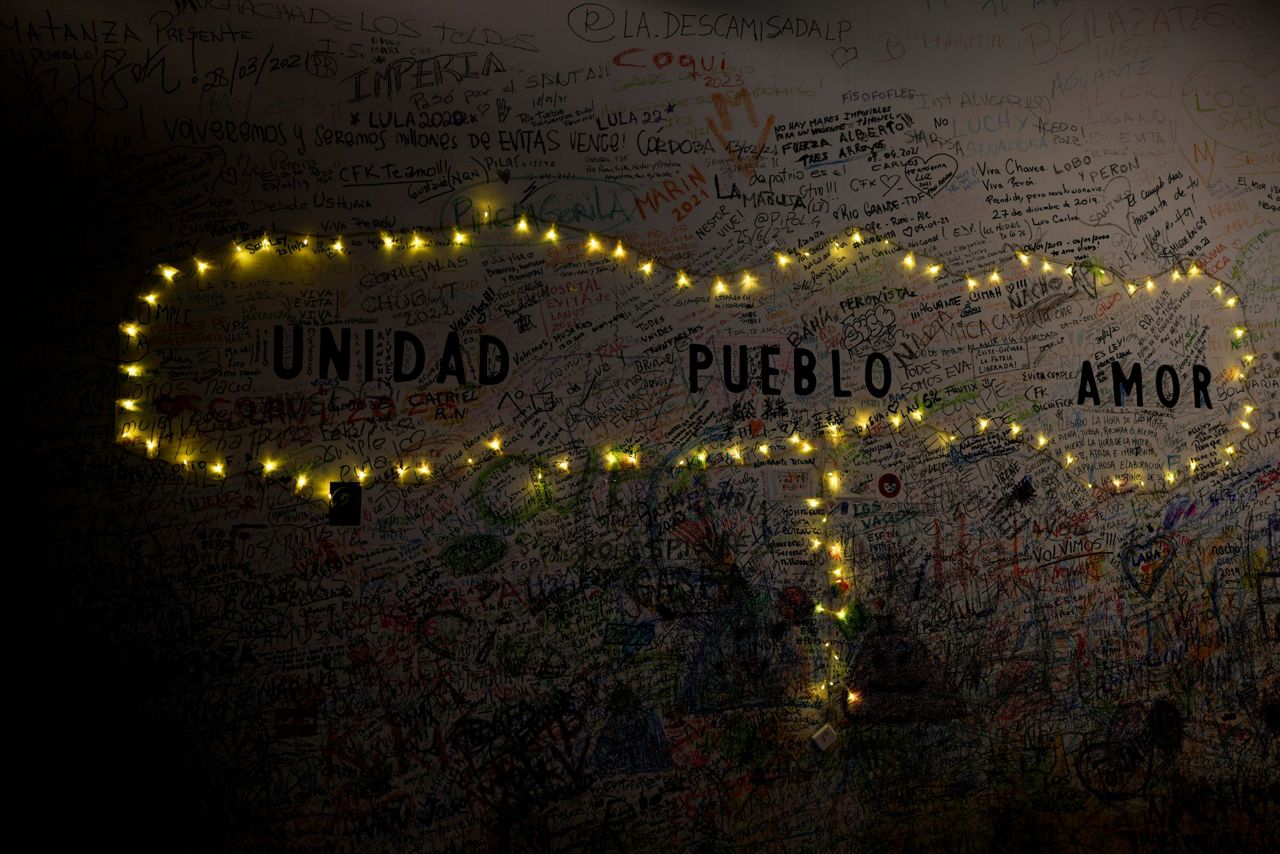

Seven decades after her death, Evita continues to awaken passions in Argentina as her followers believe her image as a champion of the poor is more relevant than ever at a time when inequality and poverty are rising as the economy remains stagnated amid galloping inflation.

Evita has been the subject of countless books, movies, TV shows and even a Broadway musical but for some of her oldest, most ardent followers the connection with the actress turned political leader is much more personal.

Juana Marta Barro was one of dozens of people who lined up Tuesday morning to leave flowers and pay her respects at Evita’s tomb, located in the Recoleta neighborhood in Argentina's capital.

With tears in her eyes, the 84-year-old Barro, daughter of a housekeeper, recalled how her life in northern Tucumán province improved after Evita came on the political scene, and she suddenly received better shoes and school uniform.

“It was thanks to her that I had my first backpack,” said Barro, who still recalls the excitement of seeing Evita pass by her town on a train. “She is a torch that shines in my heart.”

Evita was born in a modest home in Los Toldos, a small rural town some 300 kilometers (186 miles) from the capital, where she moved to when she was 15 to pursue her dream of becoming an actress. A decade later, she met Juan Domingo Perón, a military officer who was a government official.

Evita was by his side when Perón won the 1946 presidential election and went on to take an unprecedented role as a powerful first lady, putting herself at the forefront of women’s rights causes, including suffrage that was approved a year later and setting up a foundation to help workers and the poor.

As much as Evita was loved, she was equally hated by many of the country’s wealthy and powerful who were wary of her growing popularity and influence.

Her time in the spotlight was intense but brief as she died of cervical cancer at age 33, which led to an outpouring of grief in the streets as the South American country went into mourning.

Perón ended up being elected president two more times and was the founder of a political movement — Peronism — that dominates Argentine political life to this day, with many leaders of disparate ideological views claiming loyalty to the former general.

“Perón was respected, he was obeyed — you either agreed with what he said or not. But Evita was loved or hated and ended up contributing a strong dose of emotion to Peronism,” said Felipe Pigna, a historian who has written extensively about the former first lady.

For some, that emotion has lived on.

María Eva Sapire joined with almost 100 others a day before the anniversary of Evita’s death to dress up like her as part of a performance that paid homage to the former first lady.

Sapire was named after Evita and now she talks about her with her own daughter.

“When you listen to her speeches it’s amazing how so many things still fit so many years later,” Sapire said.

Others who came to admire Evita later in life, often say that it was precisely the feeling that she was advanced for her time in many issues, particularly women’s rights, that led them to join her legions of fans.

“Young people in particular see a rebel in Evita, a figure who didn’t bow her head or give up” and ended up dying “young and beautiful,” which contributed to the construction of a “pop icon," Pigna said.

“Eva is a character who bewitches,” said Alejandro Maci, director of new series “Santa Evita” that premieres Tuesday on Disney’s streaming services based on a 1995 novel by Argentine writer Tomás Eloy Martínez.

Perón and Evita continue to be the subject of criticism both within Argentina and abroad. Some, for example, say Evita used money from the state to carry out what she described as charitable works to build up her own image as a saintly figure and help her husband grow in popularity. Others also point to claims that the couple received money from the Nazis to help perpetrators of war crimes hide out in Argentina after World War II.

Cristina Alvarez Rodríguez, a great-niece of Evita who is now a minister in the Buenos Aires provincial government, said she is particularly moved by the number of “very young girls who have tattooed Evita on their skin” and now “have her as a guiding light.”

Many now are also yearning for a figure like Evita.

For some, the current government of President Alberto Fernández, who describes himself as a Peronist, has strayed from those principles.

“The Argentine people feel betrayed. Peronism never came to starve the people, and that’s what is happening now,” said Mateo Nieto, who has photos of Perón and Evita in his pizza restaurant in the northern city of Posadas, near the border with Paraguay.

Nieto said that “the government that is in power calls itself Peronist, but it really isn’t Peronism.”

“We really miss someone like Evita, it would be great to have a leader like her in this time,” he said.

Maci, the director, sees Evita as “interesting metaphor” to think about what kind of country Argentines want at a time of growing poverty and inequality.

“This woman proposed a society with greater mobility, which is exactly what Argentina does not have right now. It lacks any kind of social mobility, and if it has any, it’s downward,” he said.

Copyright 2022 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.