LOS ANGELES (AP) — When Robert F. Kennedy decided to duck through the kitchen of the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles after declaring victory in the 1968 Democratic presidential primary, Juan Romero reveled at his good fortune.

It meant the 18-year-old busboy might get to shake hands with his hero — the man he'd assured himself would be the next president of the United States — for the second time in two days.

Romero had just grasped Kennedy's hand when gunshots rang out, one of them striking the senator in the head.

Kennedy would die the next day and the teenage Mexican immigrant who had idolized him would carry the emotional burden of that encounter for most of his life.

"I remember him one time saying he felt guilty," his daughter, Josefina Guerra, said Thursday. "He thought it was his fault."

Her father explained: "''If I wouldn't have extended my hand, he wouldn't have gotten shot," she said.

Romero died Monday in a Modesto, California, hospital following a heart attack, Rigo Chacon, a longtime family friend and former TV newsman, told The Associated Press on Thursday. He was 68.

Romero, who moved from Los Angeles decades ago, spent most of his life in the Northern California cities of San Jose and Modesto, Chacon said.

He worked in construction, including concrete and asphalt paving, enjoying the often-grueling physical labor with no intention of retiring any time soon.

"Juan was a big, brawny guy, a muscular guy and seemingly in good health," said Chacon, adding his death came as a shock to family and friends.

The divorced Romero had recently met a woman and moved in with her in Modesto. He wanted to buy a house and to travel, his daughter said.

"He was happy, he was so happy," she said. "It was just such a short time."

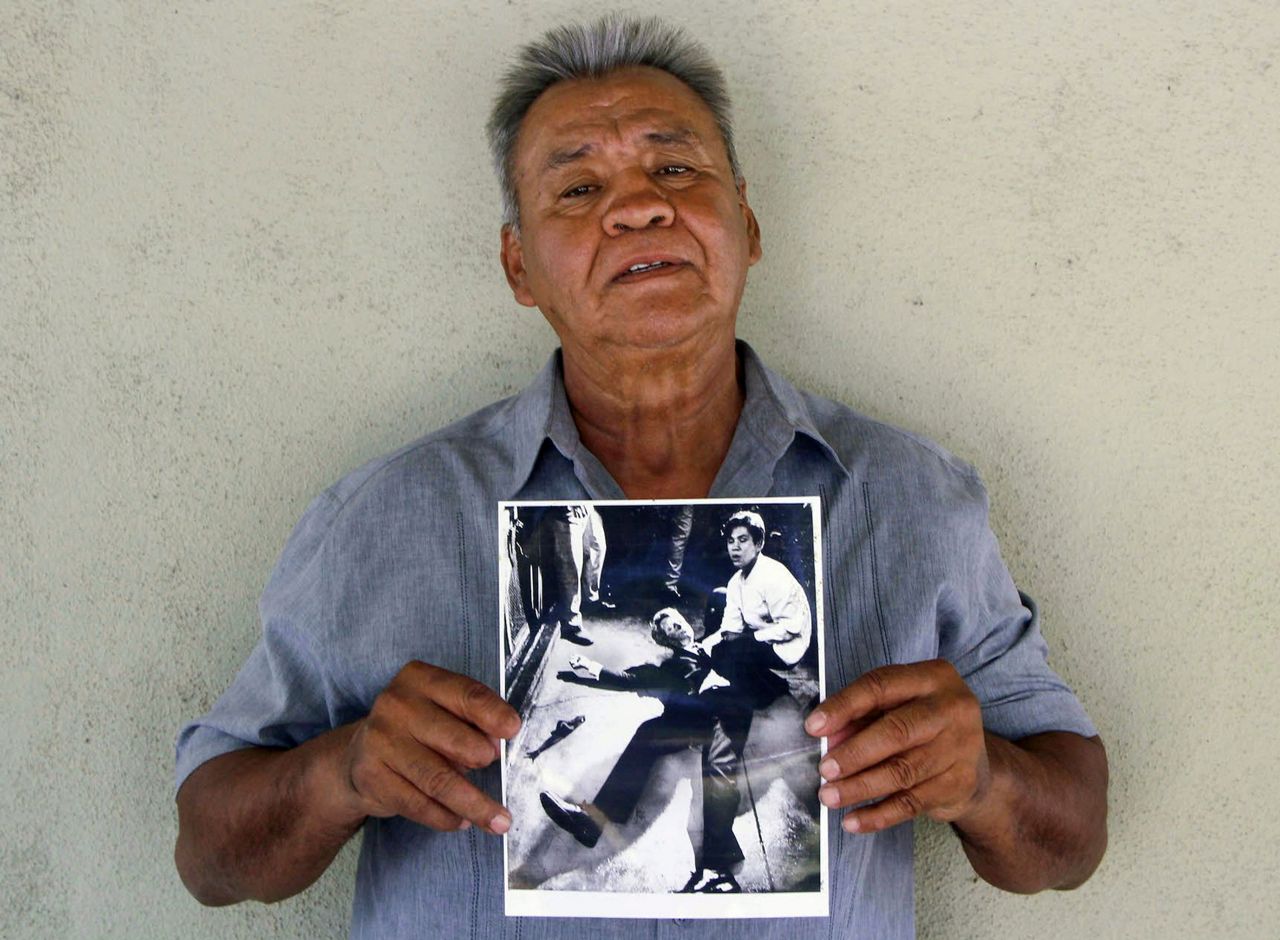

For decades, each time Romero saw black-and-white news photos of himself — a baby-faced busboy gently cradling Kennedy as he lay sprawled on the hotel's concrete kitchen floor — he would wonder what more he should have done to save Kennedy.

Only recently, he said during rare interviews this year, did he finally come to terms with that struggle.

He said he still carried the example Kennedy had set as he campaigned for equality and civil rights.

"I still have the fire burning inside of me," Romero said.

Born in the small town of Mazatan, in the Mexican state of Sonora, Romero lived in Baja California until his family received permission to bring him to the U.S. as a 10-year-old.

The family lived in blue-collar East Los Angeles and Romero was a student at Roosevelt High School in 1968, the year Chicano students started organizing walkouts to protest discrimination against Mexican-American students. As the son of a tough disciplinarian father, however, he said he was too afraid to take part.

He was working at the Ambassador Hotel the day before the June 1968 California primary when Kennedy and his aides ordered room service and he was called on to help deliver it.

"All I remember was that I kept staring at him with my mouth open," he would say later.

Finally, Kennedy approached, grabbed Romero's hand with both of his and said, "Thank you."

"I will never forget the handshake and the look ... looking right at you with those piercing eyes that said, 'I'm one of you. We're good,'" Romero said. "He wasn't looking at my skin, he wasn't looking at my age ... he was looking at me as an American."

After Kennedy won the primary he thanked supporters in the hotel's Embassy Room then cut through the kitchen for a meeting with reporters.

Romero jumped at the chance to meet him again.

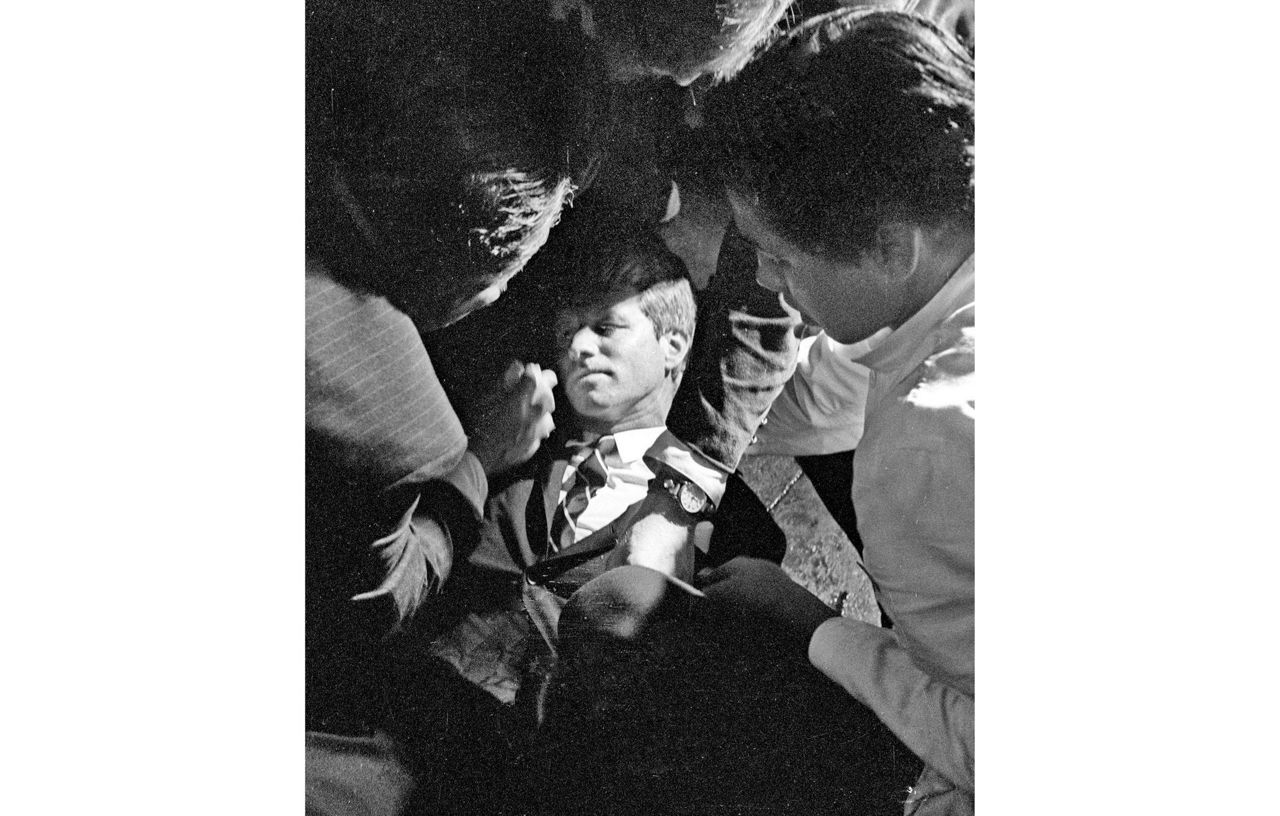

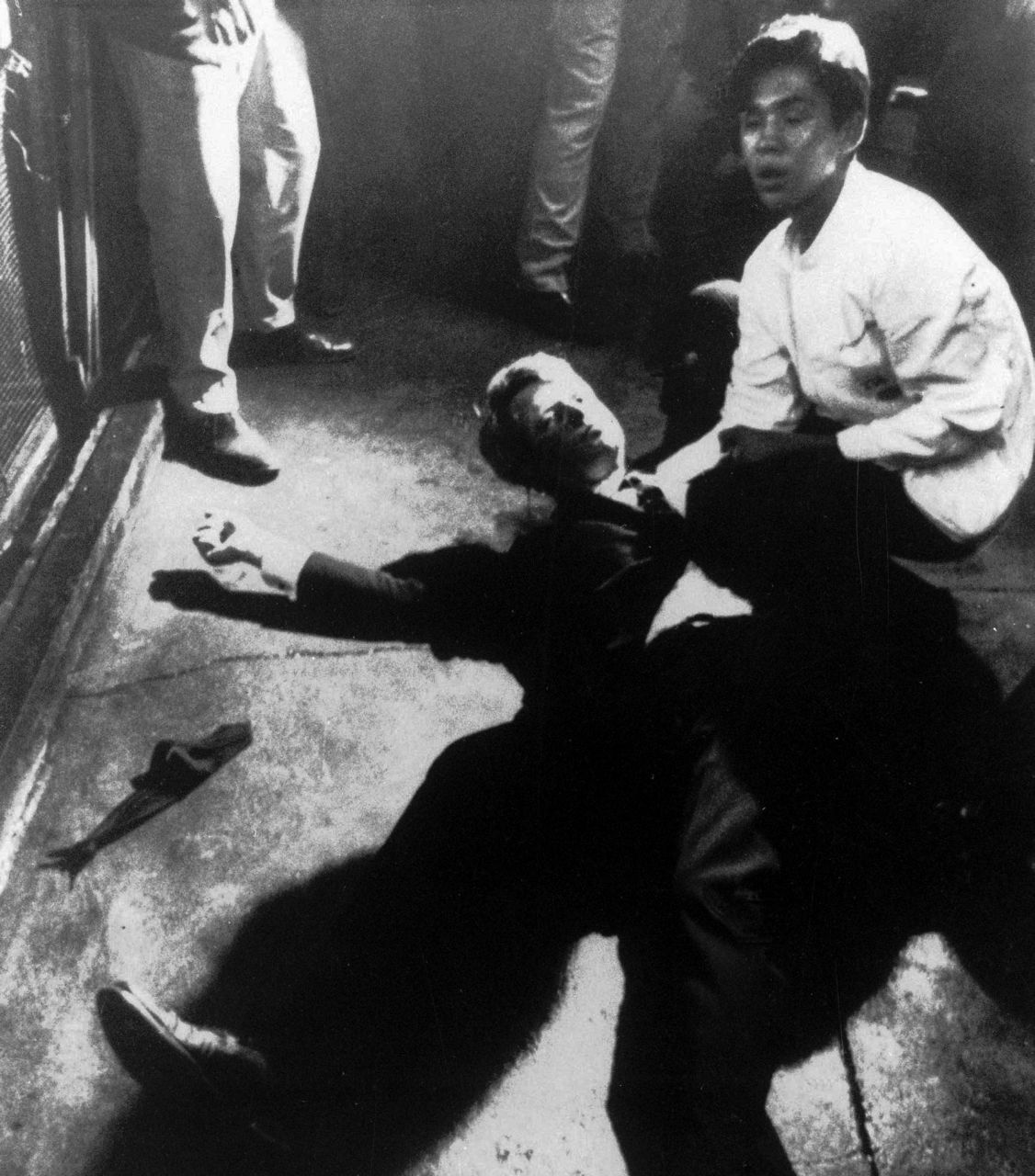

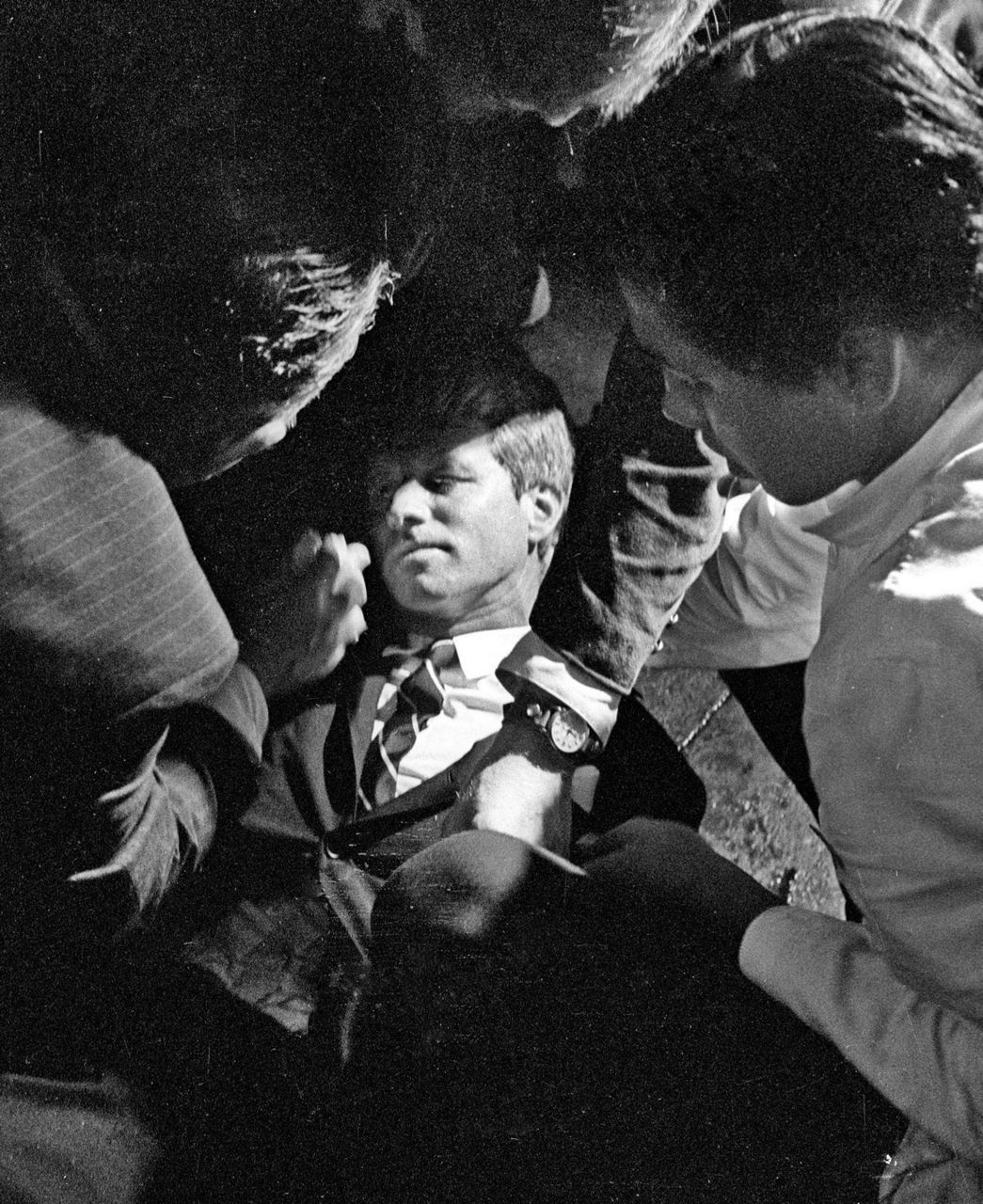

After gunfire rang out and Kennedy fell, Romero cradled his bleeding head.

"Is everybody OK?" Kennedy asked. Romero said yes.

"Everything will be OK," the senator replied shortly before losing consciousness.

As they talked, Romero pressed a set of Rosary beads into the senator's hand as news photographers frantically took pictures. Kennedy died the next day at 42.

Because of the beads, his white busboy smock and the beatific look on his face, Romero was misidentified in some early news reports as a priest.

"It was a really dramatic picture with the light coming in from the side, they were strong photos," Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer David Hume Kennerly said Thursday.

"But really the heart of it," Kennerly added, "was this unknown person was there to help Senator Kennedy when he was down. That's what has always struck me about those photos."

Josefina Guerra said her father felt guilty for years about the shooting, which she said broke his heart, and he spoke little about it to her.

"I think that's what made him a tough person, to hold everything in... as a teenager, dealing with that," she said.

When he visited Kennedy's grave at Arlington National Cemetery a few years ago, Romero wept as he spoke directly to the senator.

He "asked him for forgiveness for the fact that he didn't think he reacted soon enough," Chacon recalled. "That perhaps if he took the bullet. Or he could have pushed him out of the way."

Eventually Romero overcame his guilt, thanks in part to the support of Kennedy admirers who told him that he was an example of the type of person Kennedy embraced.

In addition to Josefina, Romero is survived by daughters Elda Romero and Cynthia Medina; a son, Greg Romero, eight grandchildren and a great-grandchild.

Funeral services will be Sunday at Chapel of Flowers in San Jose, California.

Copyright 2018 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.