BHIMTAL, India (AP) — When India's Election Commission announced last month that its code of conduct would have to be followed by social media companies as well as political parties, some analysts scoffed, saying it lacked the capacity and speed required to check the spread of fake news ahead of a multi-phase general election that begins April 11.

Just weeks later, the commission is indeed struggling to cope with the fake news swirling on Facebook, WhatsApp, YouTube, Twitter and other platforms, and even for its staff to spot it before it has spread across India, observers said Tuesday.

"Millions of voters are waking up to fake news, propaganda and hate speech inciting violence against Muslims and other minorities every day. But all the commission can do is monitor it," said Apar Gupta, a lawyer and executive director of the Internet Freedom Foundation.

Given the findings that Russia used Facebook to influence the U.S. election in 2016, India's Election Commission should have been better prepared, Gupta said.

Alarmed at the surge in misinformation, Facebook said Monday that it was removing hundreds of pages and accounts because "we don't want our services to be used to manipulate people." WhatsApp on Tuesday unveiled a helpline called Checkpoint Tipline on which people can check the authenticity of information they receive.

Examples of fake political news in India on social media abound.

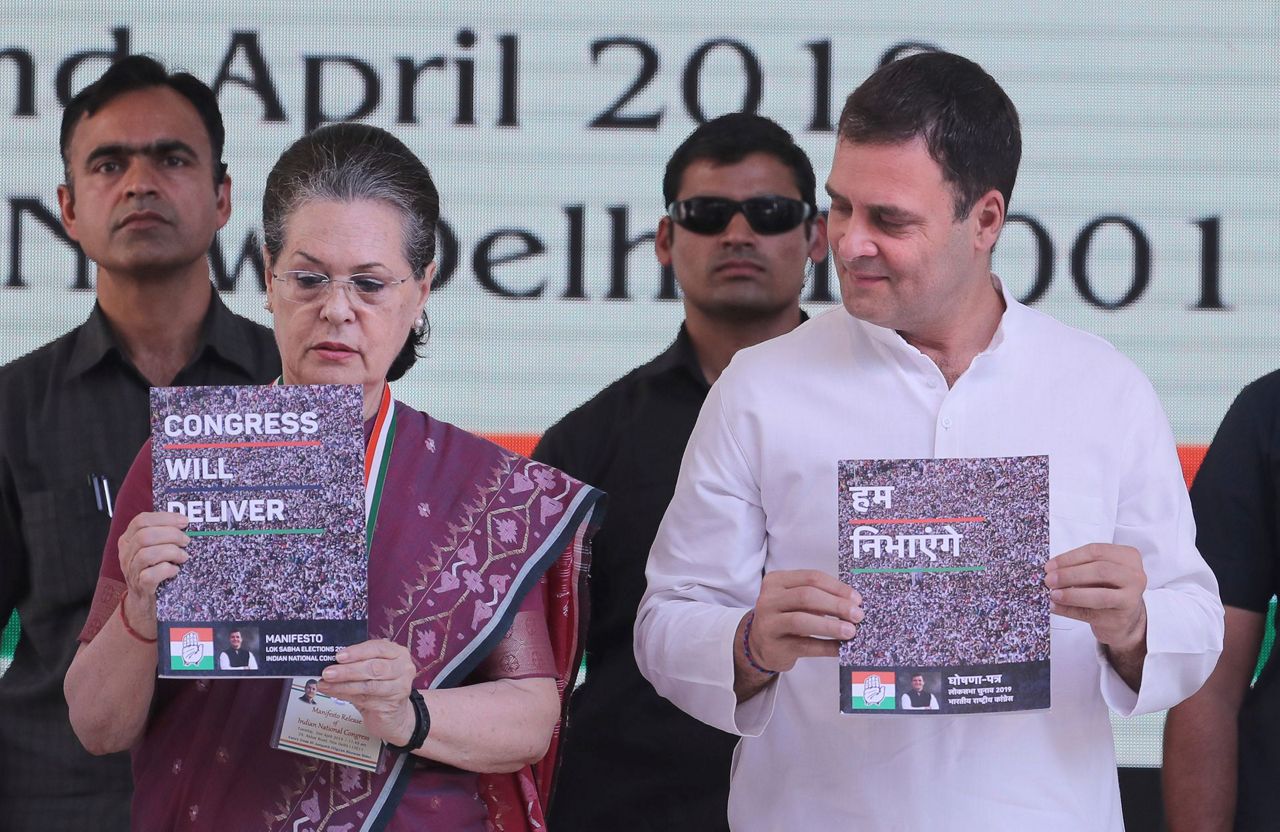

An India page on Facebook claimed that Sonia Gandhi, the ex-president of the Congress Party and mother of Rahul Gandhi, the party leader, is the country's fourth-richest woman. Another fabricated image showed the Pakistani flag being waved at Rahul Gandhi's election rallies. Yet another purported to show a photograph of Rahul Gandhi's sister Priyanka Gandhi Vadra wearing a cross around her neck, intended to malign her as a non-Hindu.

Other social media messages and images depicted Prime Minister Narendra Modi in a poor light or as a sinister force. Facebook said it had removed 687 pages or accounts that "engaged in coordinated inauthentic behavior" linked to the Congress Party.

The scale of the propaganda, false information, manipulated photos and fake videos may have something to do with the scope of India's general election. The outcome of 879 million Indians voting over five weeks starting next week is being seen by some as a watershed moment that could fundamentally alter the ethos of Indian society.

Modi's ruling Bharatiya Janata Party hopes for a second term to consolidate its pro-growth, majoritarian policies. The opposition Congress is desperate for a revival in its fortunes after a long period of a declining voter base.

With many politicians convinced the election is going to be fought on WhatsApp, political parties have created WhatsApp group chats to spread their message. Reports in the Indian media say that the BJP plans to have three WhatsApp groups for each of India's 927,533 polling booths — or 2.8 million WhatsApp groups in all. With WhatsApp recently limiting group members to a maximum of 256, the forum's group chats could potentially reach millions of voters.

For the Commission, fake news presents a huge challenge. India has 1.14 billion cellphone connections. Around 240 million Indians use WhatsApp. Facebook has over 300 million users in India, more than any other country.

In India, rumors present a real threat. In 2018, more than 30 people were lynched by mobs acting on rumors spread on WhatsApp. In response, the messaging platform limited the number of people that messages could be forwarded to in India to five from the earlier 20. But experts say that all this has meant is that the number of small groups has proliferated.

For Gupta, the Election Commission's methods for tackling fake news are woefully inadequate.

"The mechanism they have set up is that if they see any fake news, they will request the Internet and Mobile Association of India to contact Facebook or YouTube and ask them to take it down. The Association then requests the platforms to do this. This is ludicrously slow," said Gupta.

Last month, Facebook, Google, Twitter, WhatsApp and ShareChat agreed to adhere to a voluntary code of ethics in collaboration with the Election Commission to curb the menace of fake news, promising to take down any deliberately misleading information within three hours.

Palash Goorha, business director of social media analytics firm Konnect Insights, said this agreement alone was a novel and useful initiative for India's general election — the world's biggest democratic exercise. He expects it will be watched closely by other governments.

"It's the first time for such an agreement. After the Trump election, Facebook is being proactive and it's good that everyone else signed up to this. Yes, the commission is learning on the job. Yes, it will learn the hard way. But it's a start," Goorha said.

But according to Ankit Lal, head of social media with the Aam Aadmi Party, which rules New Delhi, the commission should have engaged all the parties concerned, including those who work in public policy in this field, much earlier to grasp the sheer scale of the problem and devise more concrete steps to tackle it.

"For an organized and concerted effort, the commission should have been actively engaged both with the social media companies and other groups who know much more about it than it does, long ago," Lal said. "You can't get ready for such a mammoth exercise in a few months. At present, it seems more concerned about being seen to be effective than actually being effective in preventing fake news influencing this election."

Copyright 2019 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.