One hundred years ago this month, women in the United States were guaranteed the right to vote with ratification of the 19th Amendment — secured by a 24-year-old Tennessee legislator's decisive vote, cast at the bidding of his mother.

Harry T. Burn's surprise move set the stage for decades of slow but steady advances for American women in electoral politics. Two years ago, a record number of women were elected to Congress. On Tuesday, Democratic former Vice President Joe Biden selected Sen. Kamala Harris as his running mate — making her the first Black woman on a major party’s presidential ticket.

Burn, from the small town of Niota in eastern Tennessee, joined the Legislature in 1918 as its youngest member. The following year, Congress approved the 19th Amendment, touching off the battle to win ratification by the legislatures of 36 of the 48 states.

The process moved quickly at first: By March 1920, 35 states had ratified, while eight states, mostly Southern, had rejected the amendment. Of the states yet to vote, Tennessee was the only one where ratification was considered possible under prevailing political conditions.

So all eyes turned to its Legislature, where lawmakers had the power to grant the women’s suffrage movement a victory it had sought for more than 70 years or deal it a painful setback.

At that time, women in more than half the states could vote in presidential elections. But they had no statewide voting rights throughout the South and several other states.

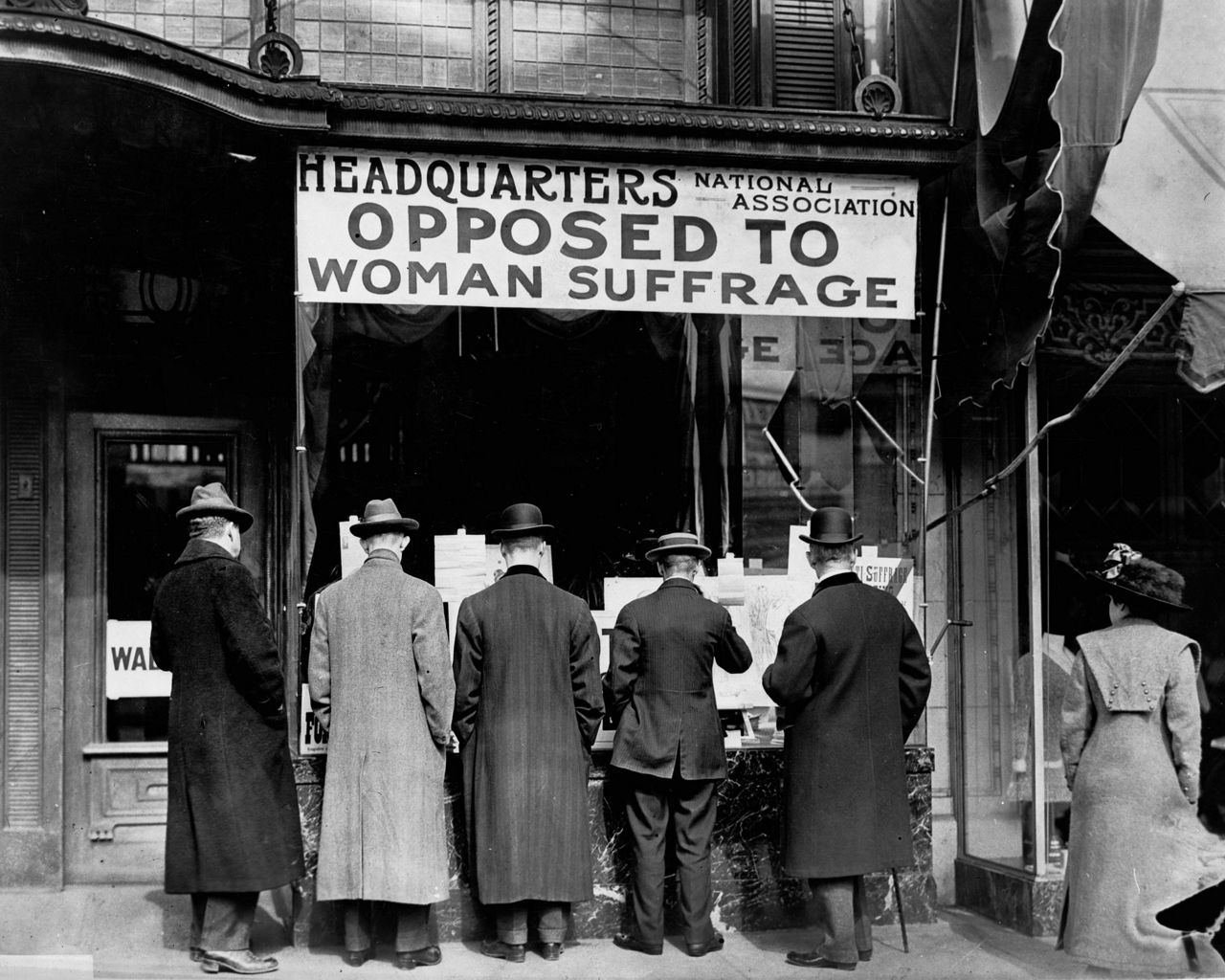

Thousands of activists on both sides of the debate poured into Nashville ahead of the special session. The posh Hermitage Hotel became a hotbed of lobbying and political gossip.

The amendment was approved 25-4 in the state Senate and sent to the House, where sentiment was divided as its turn to vote came on Aug. 18, 1920.

Anti-suffragists believed they had the votes needed to table the amendment, but that failed in a 48-48 tie. Burn was among those supporting the motion to table.

Next came the decisive vote on whether to ratify. Onlookers expected another tie, which would have doomed the measure.

But when Burn’s turn came, he switched sides. His “aye” was so unexpected that many onlookers were unsure what they’d heard, according to various historical accounts. The amendment passed 49-47.

Some wondered if Burn had been bribed. But the next day, addressing the House, he offered an explanation.

He had received a letter from his mother, urging him to buck the anti-suffragist sentiments of many of his constituents and instead support the amendment.

“Dear Son, Hurrah and vote for suffrage!” she wrote. “Don’t forget to be a good boy and help Mrs. Catt put the ‘rat’ in ratification. Your Mother.”

That was a reference to Carrie Chapman Catt, a leading suffragist who had come to Nashville to campaign for the amendment.

Burn told the House: “I believe in full suffrage as a right.” He added: “I know that a mother’s advice is always safest for her boy to follow, and my mother wanted me to vote for ratification.”

It took decades after 1920 to reach some significant milestones. For example, no woman was elected a state governor in her own right — as opposed to succeeding her husband — until Ella Grasso in Connecticut in 1975. Even now, women hold only nine of the 50 governorships and about one-fourth of the seats in Congress.

Yet women’s commitment to voting has deepened over the decades. According to the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University, American men had higher turnout rates than women in presidential elections until 1980, while women’s turnout rate has been higher ever since. In the 2016 election, according to the center, votes were cast by 73.7 million women and 63.8 million men.

The women’s suffrage movement in the United States is widely considered to have been launched at the Seneca Falls convention in New York state in 1848. At the time, many Southerners were wary of the movement because key leaders also were engaged in anti-slavery campaigning.

By the 1910s, many Southerners were viewing the proposed 19th Amendment through a racial prism, said Marjorie Spruill, an emeritus professor of history at the University of South Carolina.

“The attitude was, ’If you ratify the 19th Amendment, you’re not a good son of the South,'” Spruill said. “'These white radical women from outside are going to insist that Black women get the vote.'”

That opposition continued right through ratification. A few states on the periphery of the former Confederacy — Kentucky, Arkansas, Missouri, Texas — had preceded Tennessee in passing the amendment. But in the core of the South, opposition was solid.

Even after ratification, Black women, along with Black men, were frequently disenfranchised in Tennessee and other Southern states by Jim Crow laws with requirements for voters such as paying a poll tax, owning property and passing a literacy test.

“Black women had to continue their fight to secure voting privileges, for both men and women. ... The 19th Amendment was a starting point,” wrote Sharon Harley, a professor of African American Studies at the University of Maryland.

For white women as well, ratification did not lead swiftly to political equality. Tennessee, for example, has never elected a woman as governor, and Marsha Blackburn became its first female U.S. senator just two years ago.

Wanda Sobieski, a lawyer who led campaigns to erect suffrage memorials in her hometown of Knoxville, said women are now well represented as judges in Tennessee, including holding three of the five seats on the state Supreme Court.

But she says it’s been difficult for women to raise the funds needed to win statewide elections.

Spruill said there’s a similar pattern across the South, where only a few states have elected a woman as governor and most have opposed recent efforts to resurrect the long-derailed Equal Rights Amendment.

Mississippi, Tennessee’s neighbor to the South, was the last state to ratify the 19th Amendment, waiting 64 years before taking that step in 1984.

“In politics, sexism is alive and well,” Spruill said.

Copyright 2020 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.