WASHINGTON (AP) — Joe Biden's ambitious opening bid, his $1.9 trillion American Rescue economic package, will test the new president's relationship with Congress and force a crucial choice between his policy vision and a desire for bipartisan unity.

Biden became president this week with the pandemic having already forced Congress to approve $4 trillion in aid, including $900 billion just last month. And those efforts have politically exhausted Republican lawmakers, particularly conservatives who are panning the new proposal as an expensive, unworkable liberal wish-list.

Yet, Democrats, now with control of the House, Senate and White House, want the new president to deliver ever more sweeping aid and economic change.

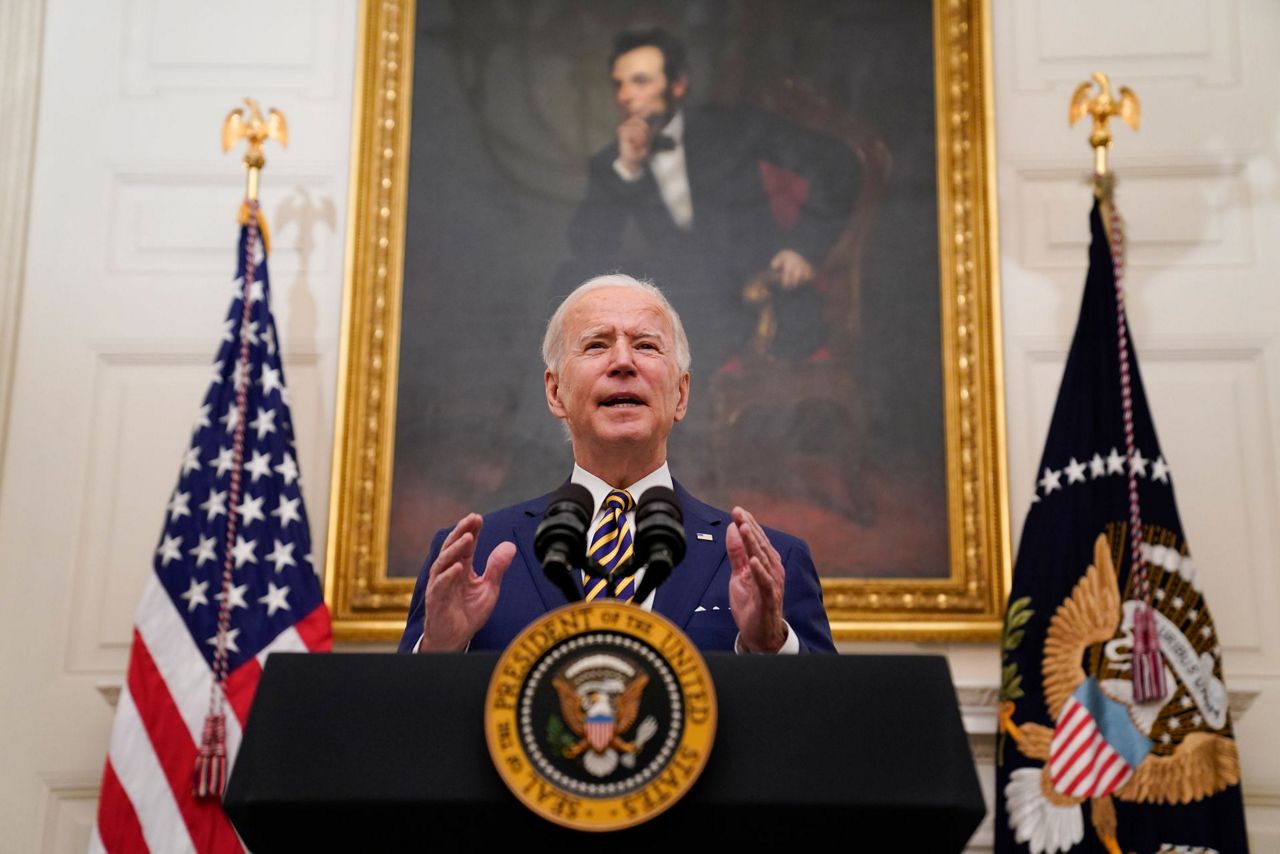

On Friday, Biden took a few beginning steps, signing executive orders at the White House. But he also declared a need to do much more and quickly, saying that even with decisive action the nation is unlikely to stop the pandemic in the next several months and well over 600,000 could die.

“The bottom line is this: We are in a national emergency. We need to act like we’re in a national emergency,” he said. "So we got to move with everything we got. We’ve got to do it together. I don’t believe Democrats or Republicans are going hungry and losing jobs, I believe, Americans are going hungry and losing jobs.”

The limits of what Biden can achieve on his own without Congress was evident in the pair of executive orders he signed Friday. The orders would increase food aid, protect job seekers on unemployment, make it easier to obtain government aid and clear a path for federal workers and contractors to get a $15 hourly minimum wage.

Brian Deese, director of the White House National Economic Council, called the orders a “critical lifeline,” rather than a substitute for the larger aid package that he said must be passed quickly.

All of this leaves Biden with a decision that his team has avoided publicly addressing, which is the trade-off ahead for the new president. He can try to appease Republicans, particularly those in the Senate whose votes will be needed for bipartisan passage, by sacrificing some of his agenda. Or, he can try to pass as much of his proposal as possible on a party-line basis.

Well aware of all that, Biden is a seasoned veteran of Capitol Hill deal-making and has assembled a White House staff already working privately with lawmakers and their aides to test the bounds of bipartisanship.

On Sunday, Deese, will meet privately with a bipartisan group of 16 senators, mostly centrists, who were among those instrumental in crafting and delivering the most recent round of COVID aid.

The ability to win over that coalition, led by Sens. Susan Collins, R-Maine, and Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., will be central to any path, a test-run for working with Congress on a bipartisan basis.

“Any new COVID relief package must be focused on the public health and economic crisis at hand,” Collins said in a Friday statement.

She said she looks forward to hearing more about “the administration’s specific proposals to assist with vaccine distribution, help keep our families and communities safe, and combat this virus so our country can return to normal.”

The Biden team's approach could set the tenor for the rest of his presidency, showing whether he can provide the partisan healing that he called for in Wednesday's inaugural address and whether the narrowly split Senate will prove a trusted partner or a roadblock to the White House agenda.

“The ball will be in Biden’s court to decide how much he is going to insist on and at what cost,” said William Galston, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. “As the old saw goes, you never get a second chance to make a first impression.”

Most economists believe the United States can rebound with strength once people are vaccinated from the coronavirus, but the situation is still dire as the disease has closed businesses and schools. Nearly 10 million jobs have been lost since last February, and nearly 30 million households lack secure access to food.

One of the orders that Biden signed Friday asks the Agriculture Department to consider adjusting the rules for food assistance, so the government could be obligated to provide more money to the hungry. It also makes it easier for people to claim payments and benefits provided by the government. In addition, it would create a guarantee that workers could still collect unemployment benefits if they refuse to take jobs that could jeopardize their health.

Biden's second executive order would restore some union bargaining rights revoked by the Trump administration, protect the civil service system from changes made in the Trump years and promote a $15 hourly minimum wage for all federal workers.

But neither of the orders would have the transformative potential of another round of Congress-passed stimulus. Biden's plan includes $400 billion for national vaccinations and school reopenings, as well as direct payments of $1,400 to eligible adults, state and local government aid and expanded tax credits for children and childcare.

Pushing for both bipartisanship and the full contents of their stimulus plan, Biden officials have signaled that the price tag and contents could change but have declined to provide any specifics.

“The final package may not look exactly like the package that he proposed, that’s OK, that’s how the process, the legislative process should work,” White House press secretary Jen Psaki said Friday.

Republican lawmakers want to tackle the pandemic, though they see much of the package as overly Democratic with its nationwide $15 minimum wage and aid to state and local governments.

Republican Sen. Rick Scott of Florida, who leads the GOP senators’ reelection efforts, said the Biden proposal would "spend too much of the $1.9 trillion dollars in taxpayer money on liberal priorities that have nothing to do with the coronavirus.”

Sen. John Thune of South Dakota, the second-ranking Republican, told reporters Friday there simply won’t be Republican votes for a package “in that price range.”

Thune had delivered a Senate speech on Biden's first full day in office advising the new president, “If there was any mandate given in this election, it was a mandate for moderation."

Copyright 2021 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.