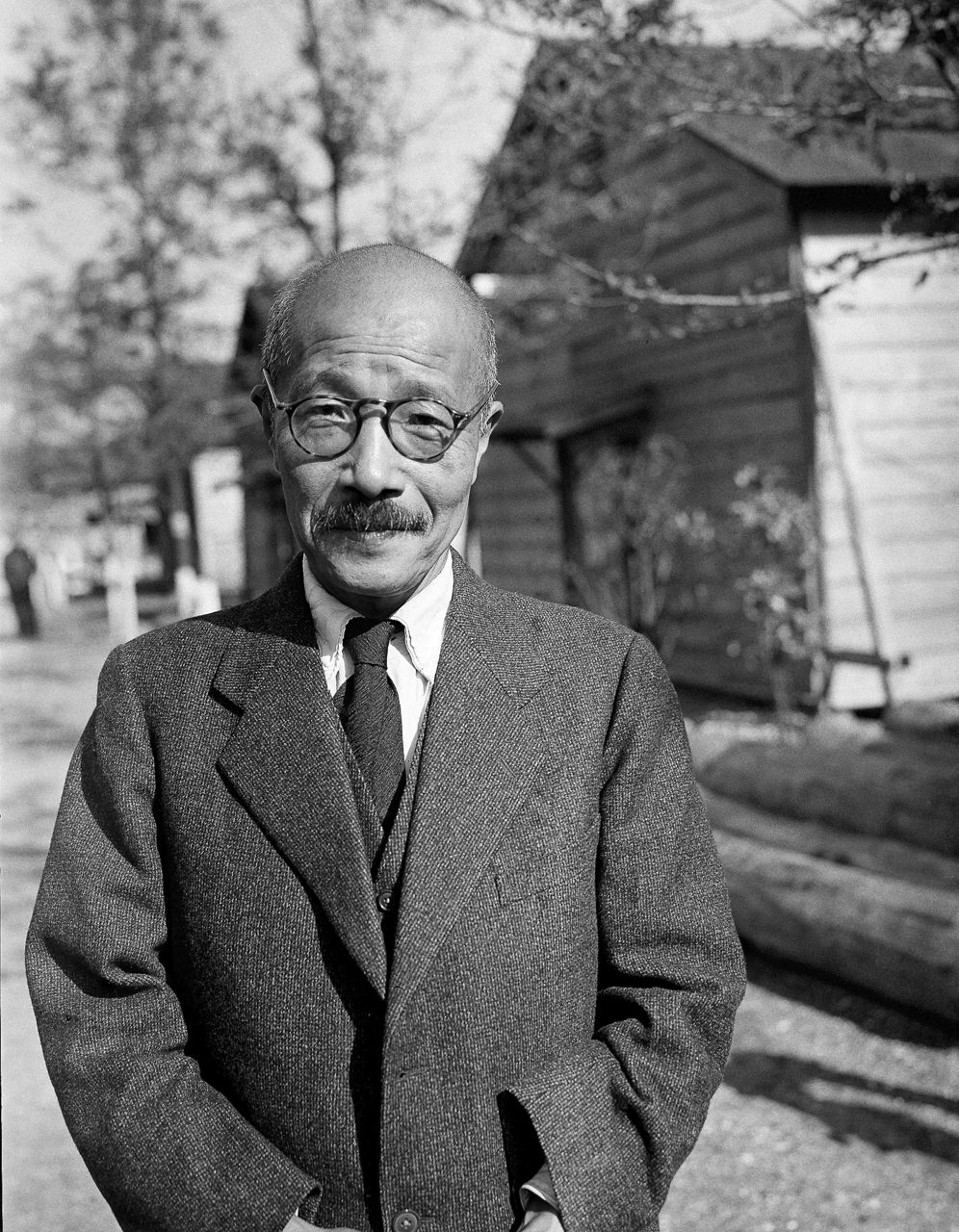

TOKYO (AP) — Until recently, the location of executed wartime Japanese Prime Minister Hideki Tojo's remains was one of World War II's biggest mysteries in the nation he once led.

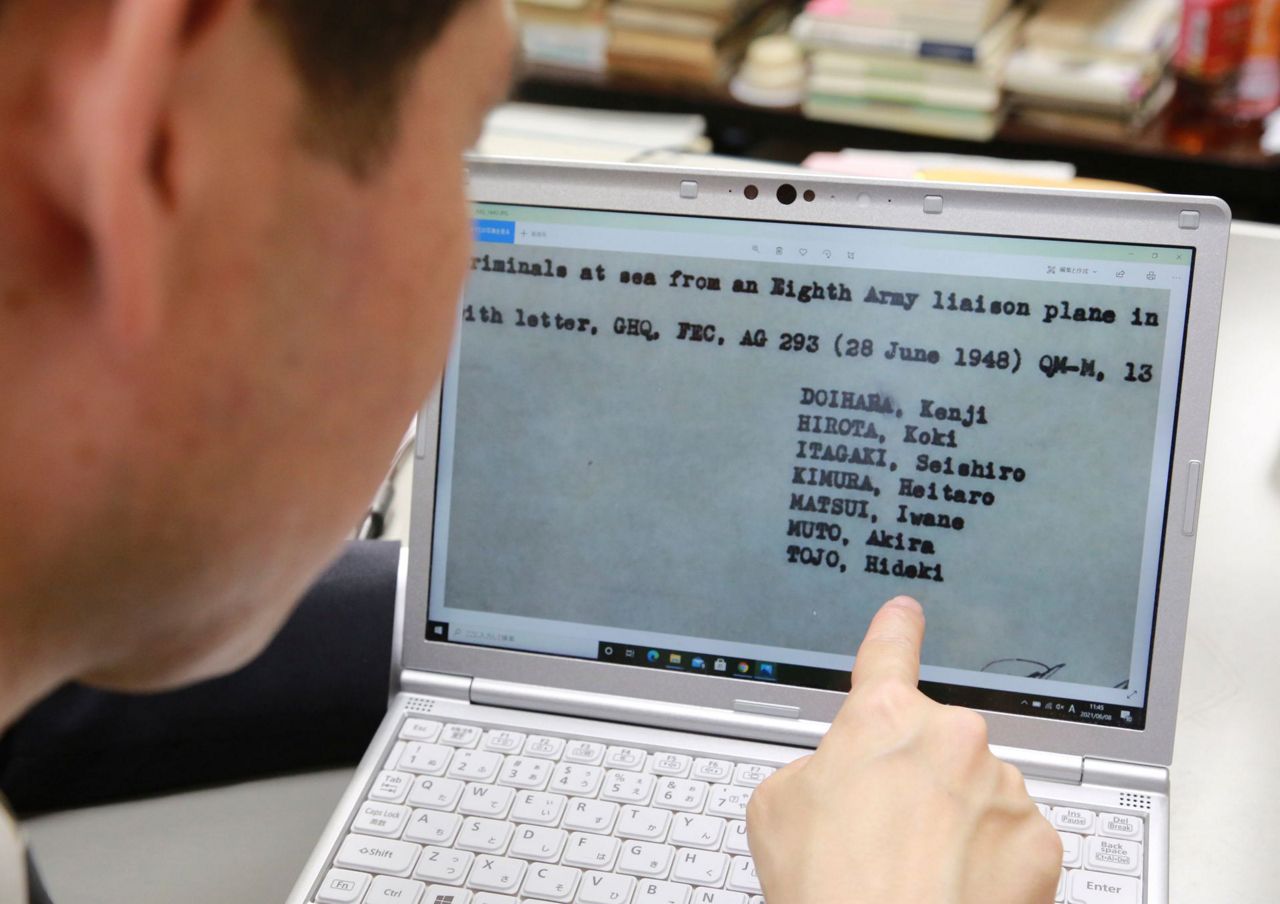

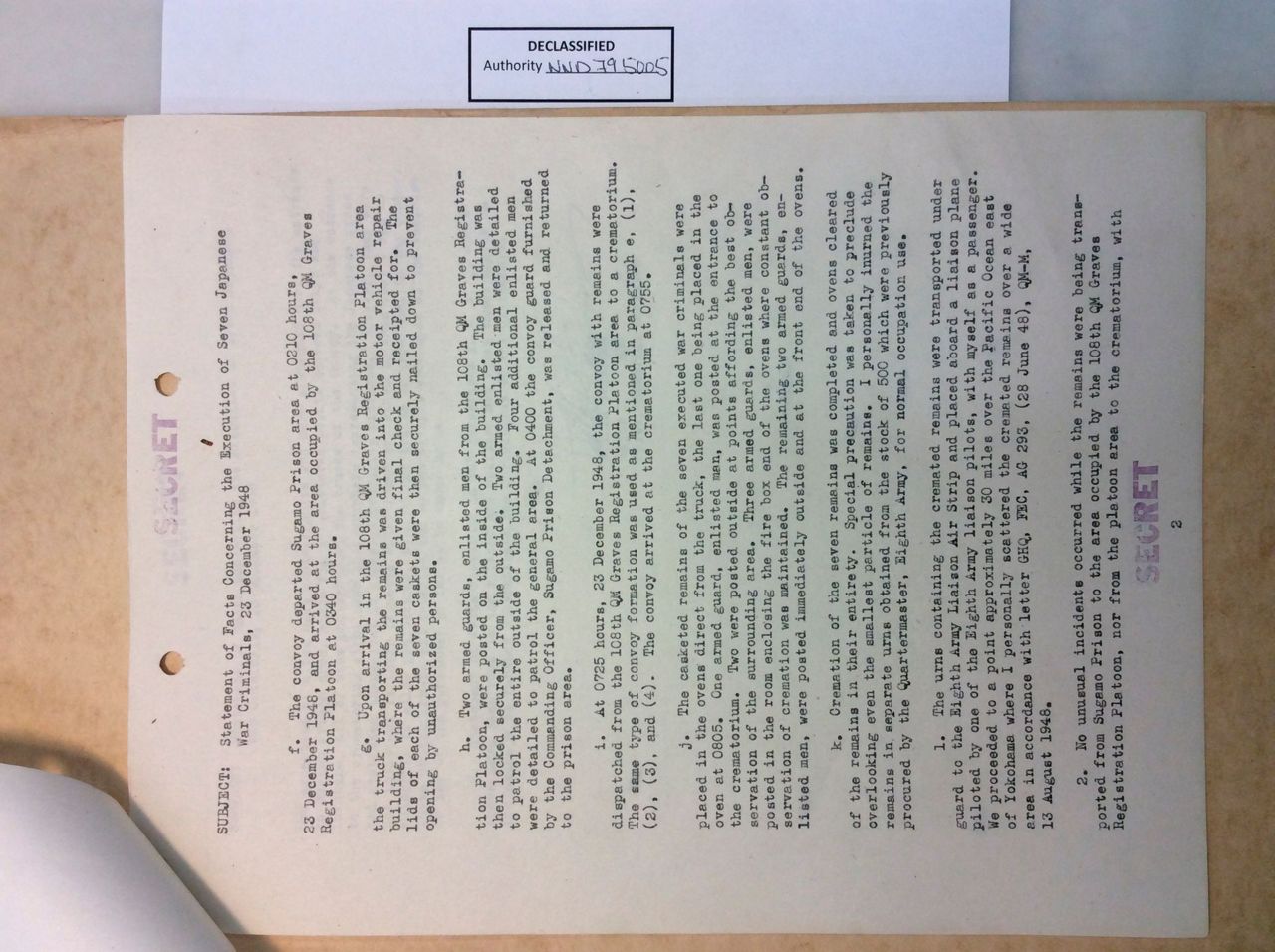

Now, a Japanese university professor has revealed declassified U.S. military documents that appear to hold the answer.

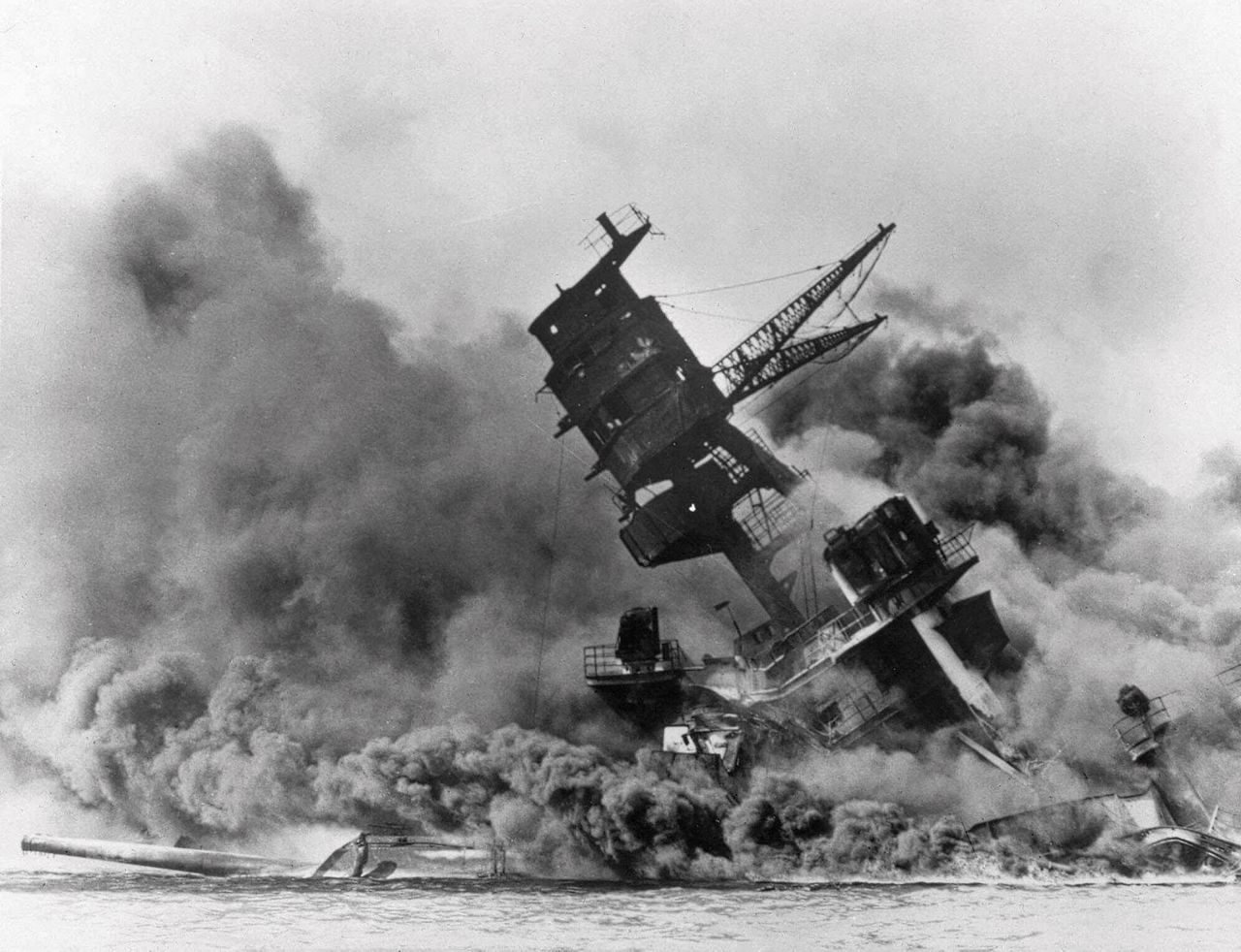

The documents show the cremated ashes of Tojo, one of the masterminds of the Pearl Harbor attack, were scattered from a U.S. Army aircraft over the Pacific Ocean about 30 miles (50 kilometers) east of Yokohama, Japan’s second-largest city, south of Tokyo.

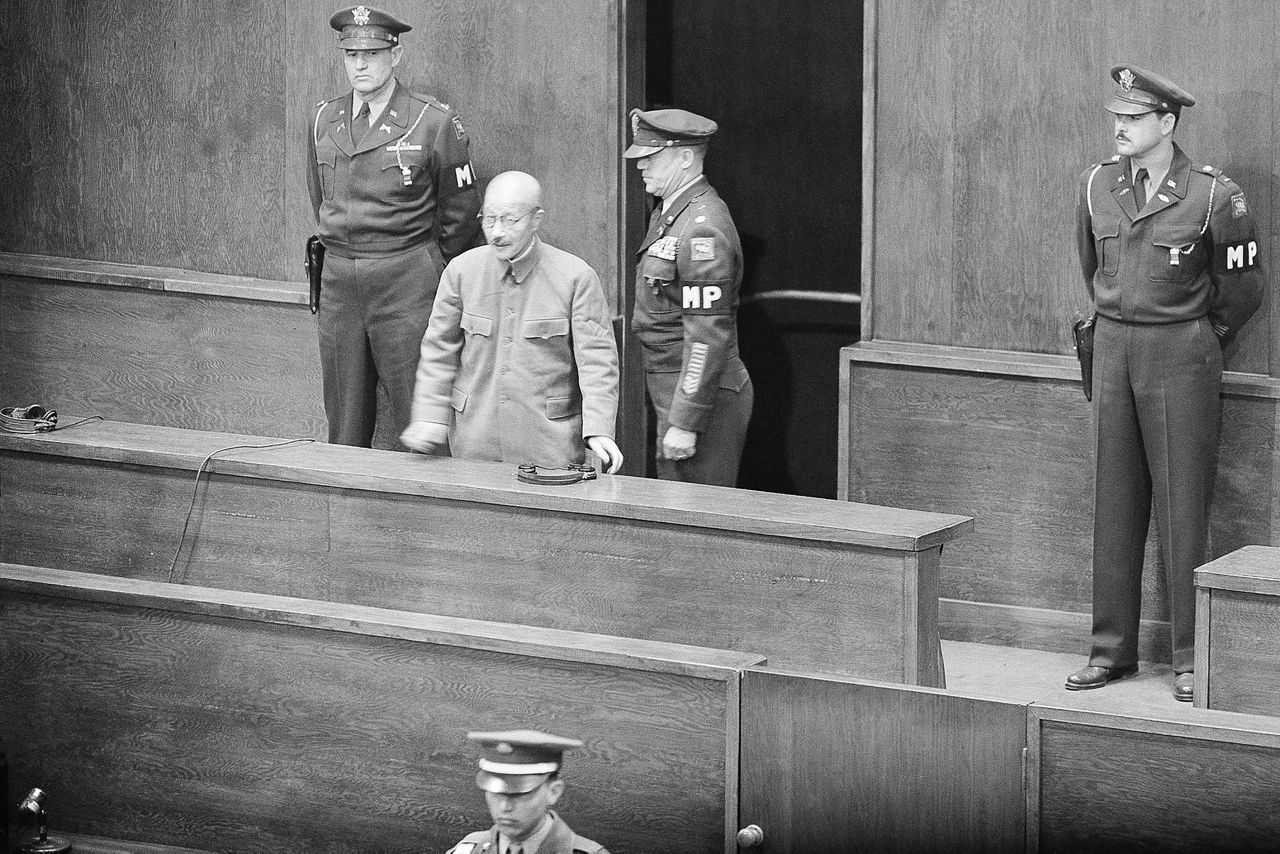

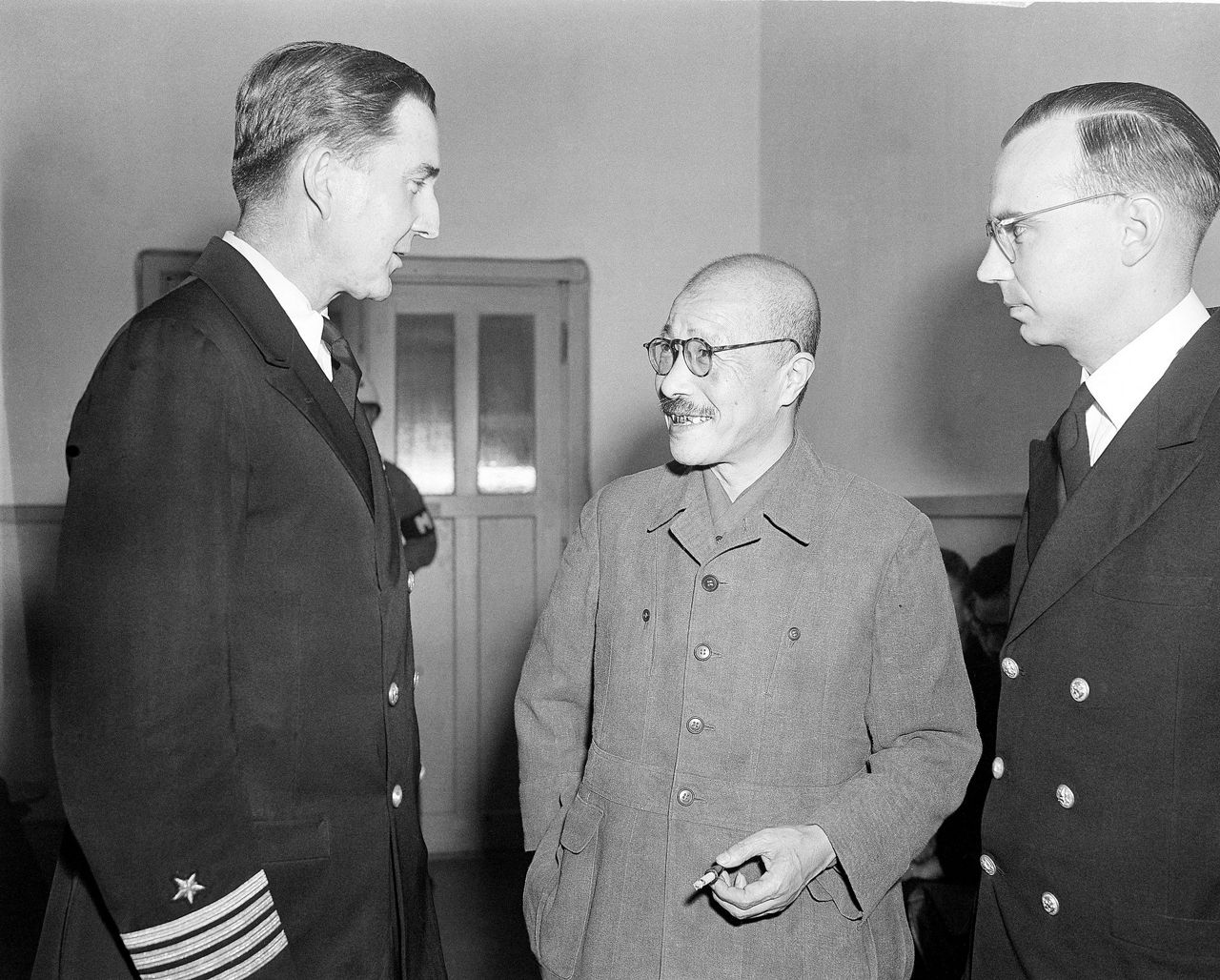

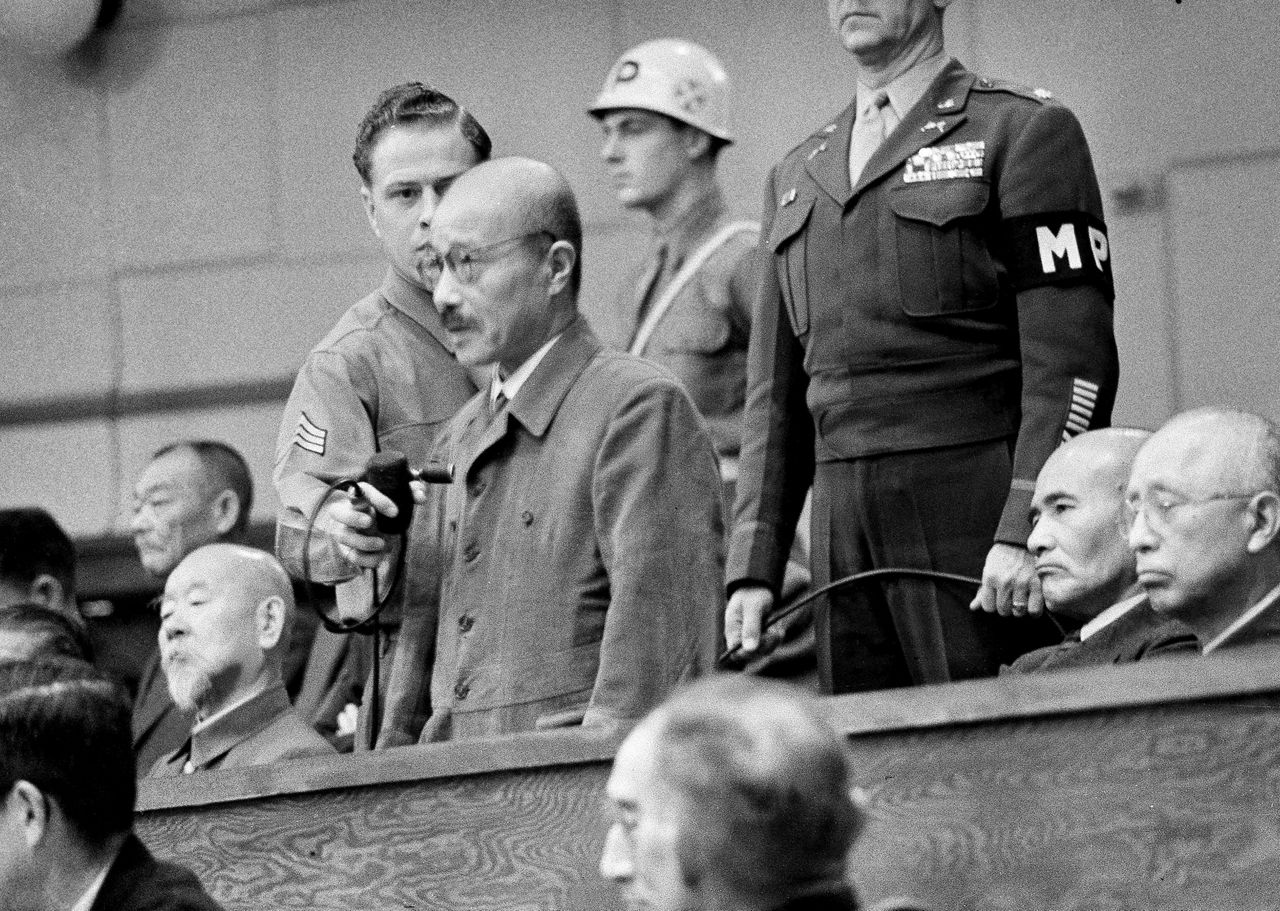

It was a tension-filled, highly secretive mission, with American officials apparently taking extreme steps meant to keep Tojo's remains, and those of six others executed with him, away from ultra-nationalists looking to glorify them as martyrs. The seven were hanged for war crimes just before Christmas in 1948, three years after Japan’s defeat.

The discovery brings partial closure to a painful chapter of Japanese history that still plays out today, as conservative Japanese politicians attempt to whitewash history, leading to friction with wartime victims, especially China and South Korea.

After years spent verifying and checking details and evaluating the significance of what he'd found, Nihon University Professor Hiroaki Takazawa publicly released the clues to the remains' location last week. He came across the declassified documents in 2018 at the U.S. National Archives in Maryland. It’s believed to be the first time official documents showing the handling of the seven war criminals’ remains were made public, according to Japan's National Institute for Defense Studies and the Japan Center for Asian Historical Records.

Hidetoshi Tojo, the leader's great-grandson, told The Associated Press that the absence of the remains has long been a humiliation for the bereaved families, but he's relieved the information has come to light.

“If his remains were at least scattered in Japanese territorial waters ... I think he was still somewhat fortunate,” Tojo said. “I want to invite my friends and lay flowers to pay tribute to him" if further details about the remains' location becomes available.

Hideki Tojo, prime minister during much of World War II, is a complicated figure, revered by some conservatives as a patriot but loathed by many in the West for prolonging the war, which ended only after the U.S. atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

About a month after Aug. 15, 1945, when then-Emperor Hirohito announced Japan’s defeat to a stunned nation, Tojo shot himself in a failed suicide attempt as he was about to be arrested at his modest Tokyo home.

Takazawa, the Nihon University professor specializing in war tribunal issues, found the documents during research at the U.S. archives into other war crimes trials. The documents, he said, are valuable because they officially detail previously little-known facts about what happened and provide a rough location of where the ashes were scattered.

He plans to continue research into other executions. More than 4,000 people were convicted of war crimes in other international tribunals, and about 920 of them were executed.

Tojo and the six others who were hanged were among 28 Japanese wartime leaders tried for war crimes at the 1946-1948 International Military Tribunal for the Far East. Twenty-five were convicted, including 16 sentenced to life in prison, with two getting shorter prison terms. Two others died while on trial and one case was dropped.

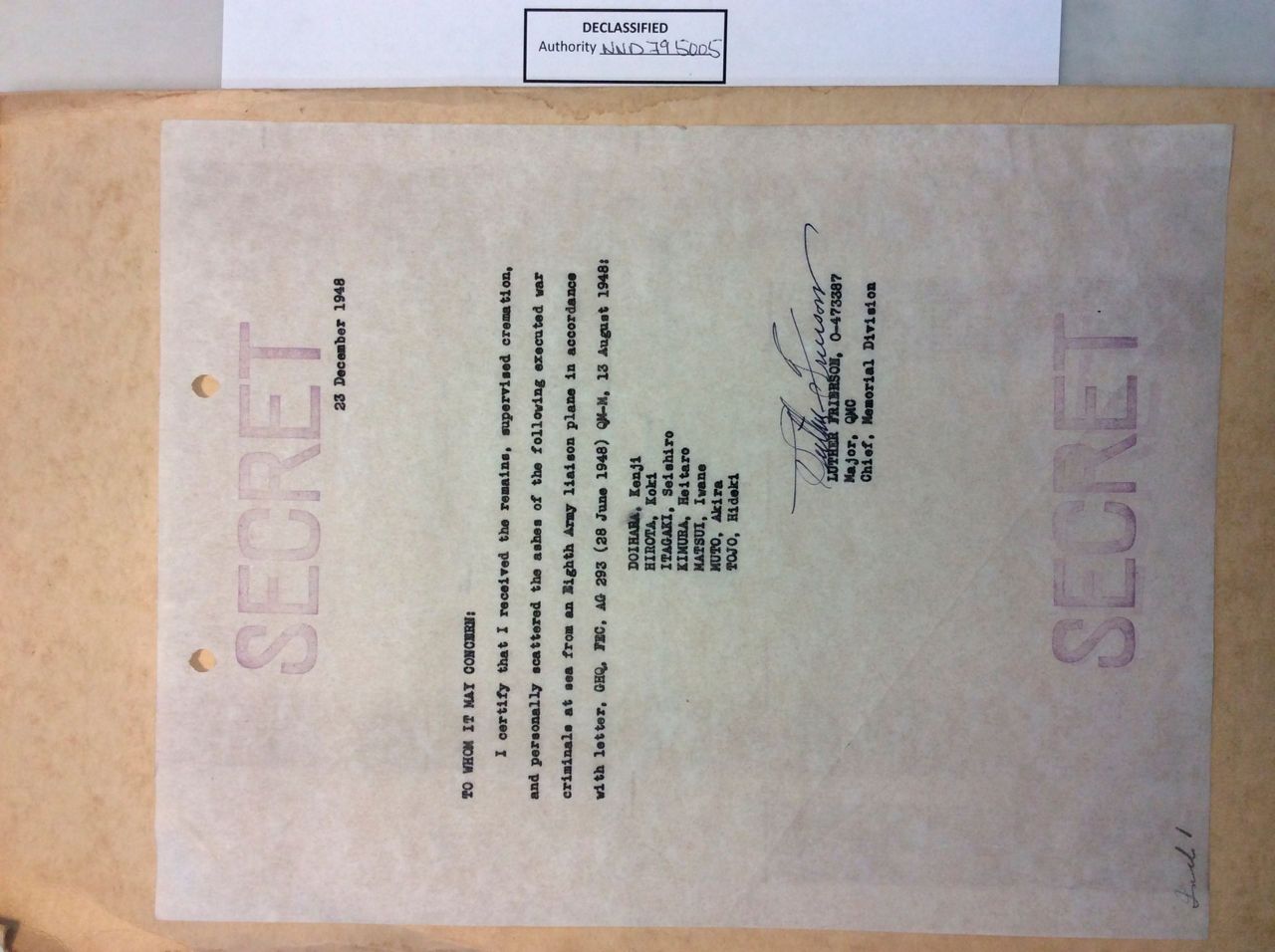

In one of the newly revealed documents — dated Dec. 23, 1948 and carrying a “secret” stamp — U.S. Army Maj. Luther Frierson wrote: "I certify that I received the remains, supervised cremation, and personally scattered the ashes of the following executed war criminals at sea from an Eighth Army liaison plane."

The entire operation was tense, with U.S. officials extremely careful about not leaving a single speck of ashes behind, apparently to prevent them from being stolen by admiring ultra-nationalists, Takazawa said.

“In addition to their attempt to prevent the remains from being glorified, I think the U.S. military was adamant about not letting the remains return to Japanese territory ... as an ultimate humiliation," Takazawa said.

The documents state that when the cremation was completed, the ovens were "cleared of the remains in their entirety.”

“Special precaution was taken to preclude overlooking even the smallest particles of remains,” Frierson wrote.

Here's how the operation went.

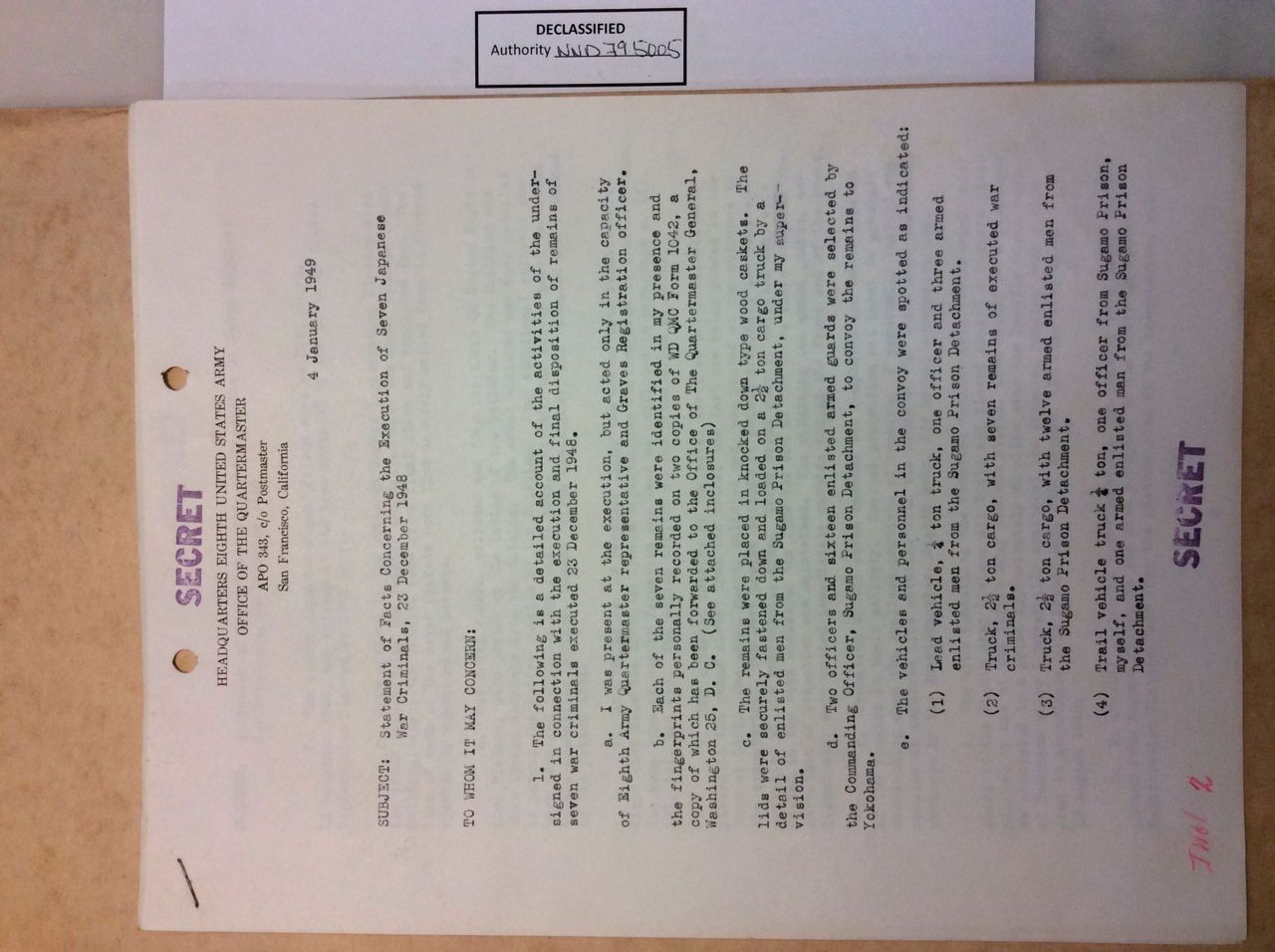

At 2:10 a.m. on Dec. 23, 1948, caskets carrying the bodies of Tojo and the six others were loaded on a 2.5-ton truck and taken out of the prison after fingerprinting for verification, Frierson wrote in a Jan. 4, 1949 document.

About an hour and a half later, the motorcade guarded by truckloads of armed soldiers to protect the bodies arrived at a U.S. military graves registration platoon in Yokohama for a final check.

The truck left the area at 7:25 a.m. and arrived at a Yokohama crematorium 30 minutes later. The caskets were unloaded from the truck and placed directly “in the ovens” in 10 minutes, while soldiers guarded the area.

The remains were then transported under guard to a nearby airstrip and loaded onto a plane that Frierson boarded. “We proceeded to a point approximately 30 miles over the Pacific Ocean east of Yokohama where I personally scattered the cremated remains over a wide area.”

Today, even without the ashes, bereaved families and conservative Japanese lawmakers such as former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe regularly pay tribute at Tokyo’s Yasukuni Shrine, where the executed war criminals are enshrined with 2.5 million war dead considered “sacred spirits” in the Shinto religion. No remains are enshrined at Yasukuni.

After the seven executed war criminals were enshrined there in 1978, Yasukuni has become a flashpoint between Japan and its neighbors China and South Korea, who see the enshrinement as proof of Japan’s lack of remorse over its wartime aggression. Yasukuni also enshrines five other convicted wartime leaders and hundreds of other war criminals.

Hidetoshi Tojo said his great-grandfather was consistently made a taboo in postwar Japan, never glorified.

“Everything about my great-grandfather was sealed, including his speeches. Taking that into consideration, I think not preserving the remains was part of the occupation policy,” he said. “I hope to see further revelations about the unknown facts of the past.”

___

This story has been corrected to say the documents were found at the U.S. National Archives in Maryland, not Washington.

___

Follow Mari Yamaguchi on Twitter at https://www.twitter.com/mariyamaguchi

Copyright 2021 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.