A young woman climbs to the top of a car in the middle of Mashhad, a conservative Iranian city famed for its Islamic shrines. She takes off her headscarf and starts chanting, “Death to the dictator!” Protesters nearby join in and cars honk in support.

For many Iranian women, it’s an image that would have been unthinkable just a decade ago, said Fatemeh Shams, who grew up in Mashhad.

“When you see Mashhad women coming to the streets and burning their veils publicly, this is really a revolutionary change. Iranian women are putting an end to a veiled society and the compulsory veil,” she said.

Iran has seen multiple eruptions of protests over the past years, many of them fueled by anger over economic difficulties. But the new wave is showing fury against something at the heart of the identity of Iran’s cleric-led state: the compulsory veil.

Iran’s Islamic Republic requires women to cover up in public, including wearing a “hijab” or headscarf that is supposed to completely hide the hair. Many Iranian women, especially in major cities, have long played a game of cat-and-mouse with authorities, with younger generations wearing loose scarves and outfits that push the boundaries of conservative dress.

That game can end in tragedy. A 22-year-old woman, Mahsa Amini, was arrested by morality police in the capital Tehran and died in custody. Her death has sparked nearly two weeks of widespread unrest that has reached across Iran’s provinces and brought students, middle-class professionals and working-class men and women into the streets.

Iranian state TV has suggested that at least 41 protesters and police have been killed. An Associated Press count of official statements by authorities tallied at least 13 dead, with more than 1,400 demonstrators arrested.

A young woman in Tehran, who said she has continually participated in the past week’s protests in the capital city, said the violent response of security forces had largely reduced the size of demonstrations.

“People still are coming to the streets to find one meter of space to shout their rage but they are immediately and violently chased, beaten and taken into custody, so they try to mobilize in four- to five-person groups and once they find an opportunity they run together and start to demonstrate,” she said, speaking on condition of anonymity.

“The most important protest they (Iranian women) are doing right now is taking off their scarves and burning them,” she added. “This is a women’s movement first of all, and men are supporting them in the backline.”

A writer and rights activist since her student days at Tehran University, Shams participated in the mass anti-government protests of 2009 before having to flee Iran.

But this time is different, she said.

Waves of violent repression against protests in the past 13 years “have disillusioned the traditional classes of society” that once were the backbone of the Islamic Republic, said Shams, who now lives in the United States.

The fact that there have been protests in conservative cities like Mashhad or Qom — the historic center of Iran’s clergy — is unprecedented, she said.

“Every morning I wake up and I think, is this actually happening? Women making bonfires with veils?”

Modern Iranian history has been full of unexpected twists and turns.

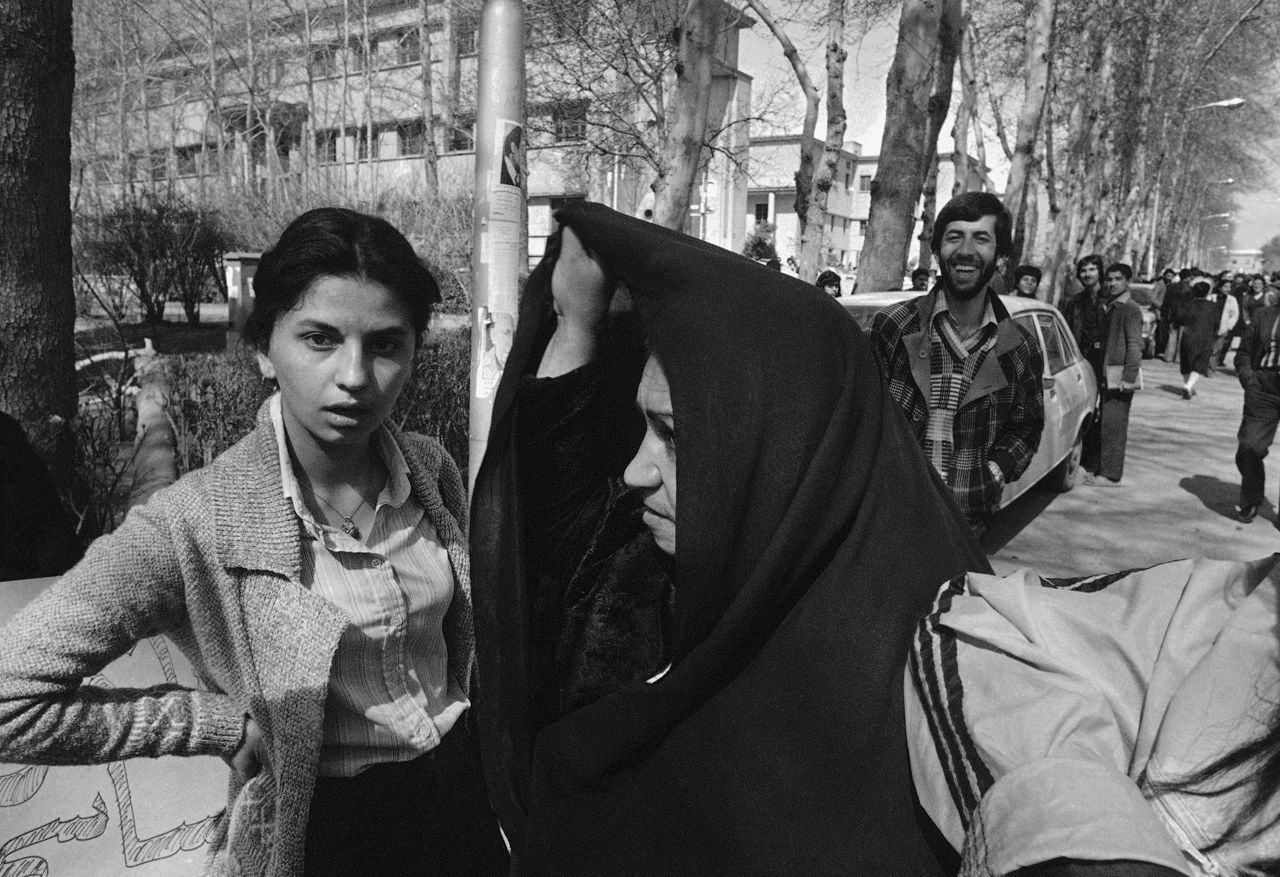

Iranian women who grew up before the overthrow of the monarchy in 1979 remember a country where women were largely free to choose how they dressed.

People of all stripes, from leftists to religious hardliners, participated in the revolution that toppled the shah. But in the end, it was Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and his followers who ended up seizing power and creating a Shiite cleric-led Islamic state.

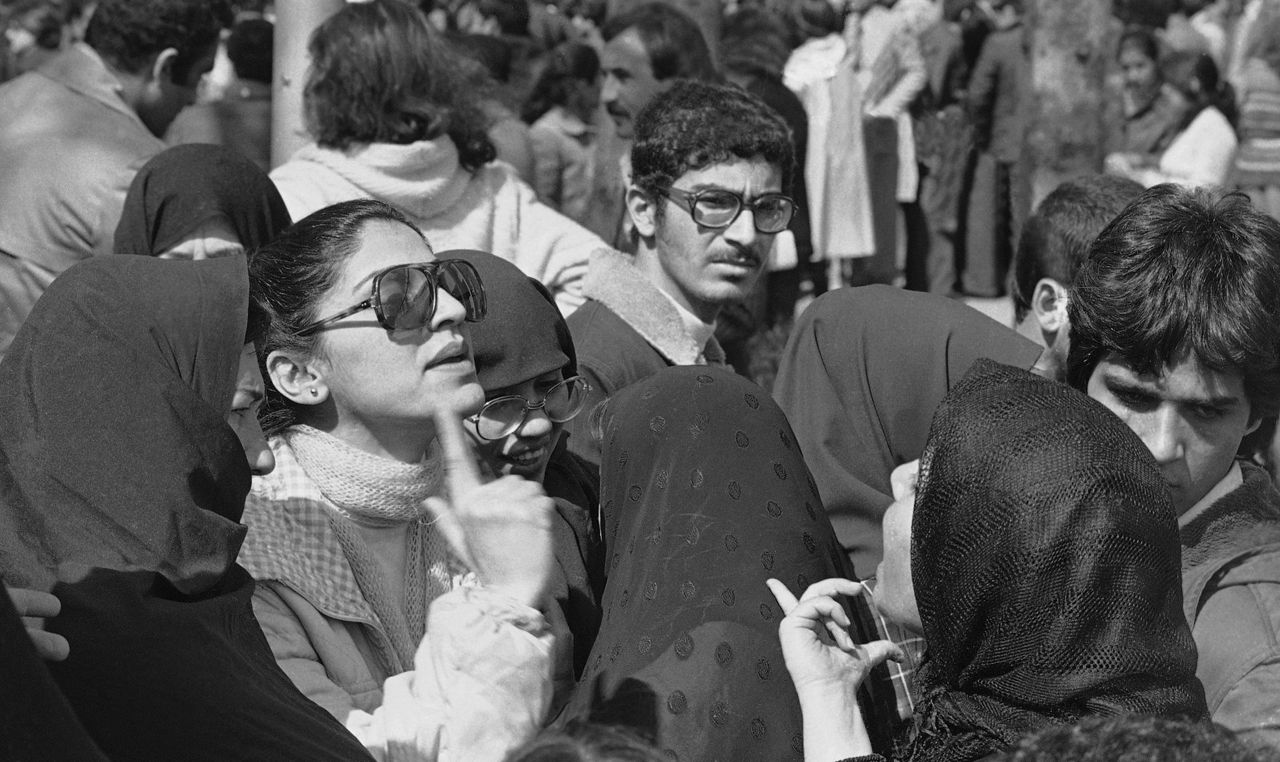

On March 7, 1979, Khomeini announced that all women must wear hijab. The very next day — International Women’s Day — tens of thousands of unveiled women marched in protest.

“It was really the first counter-revolutionary movement,” said Susan Maybud, who participated in those marches and was then working as a news assistant with the foreign press. “It wasn’t just about the hijab, because we knew what was next, taking away women’s rights.” She didn’t even own a hijab at the time, she recalled.

“What you’re seeing today is not something that just happened. There’s been a long history of women protesting and defying authority” in Iran.

“History and recent events in Iran leave us in no doubt. Women’s desire to be free to choose could not be strangled or silenced,” explained Farzaneh Milani, an Iranian scholar and professor at the University of Virginia's gender studies department.

Iranian society has struggled with allowing women the right to choose their own dress and veiling since the mid-19th century, when the poet and religious scholar Tahereh dramatically appeared unveiled before a congregation of men in 1848, Milani said. A few years after her unveiling, public authorities executed Tahereh.

A century or more ago, strict veiling was largely limited to Iran’s upper classes. Most women were in rural areas and worked, “so hijab wasn’t exactly possible” for them, said Esha Momeni, an Iranian activist and scholar affiliated with UCLA’s Gender Studies Department.

Many women wore a “roosari” or casual headscarf that was “part of traditional clothing rather than having a very religious meaning to it.”

Throughout the late 19th century, women were front-and-center in street protests, she said. In Iran’s first democratic uprising of 1905, many towns and cities formed local women’s rights committees.

This was followed by a period of top-down secularizing reforms under the military officer-turned-king Reza Shah, who banned the wearing of the veil in public in the 1930s.

During the Islamic Revolution, women’s hijab became an important political symbol of the country “entering this new Islamic era,” Momeni said. Growing up in Tehran, she remembers “living between two worlds” where family and friends didn’t wear the veil at private gatherings but feared harassment or arrest by police or pro-government militias in public.

In 2008, Momeni was arrested and kept in solitary confinement for a month at Tehran’s notorious Evin Prison, after working on a documentary about women activists and the 1 Million Signatures Campaign that aimed to reform discriminatory laws against women. She was later released and joined the 2009 “Green Movement” protests.

Like Shams, she sees today’s wave of protests as shaking the foundations of the Islamic Republic.

“People are done with the hope of internal reform. People not wanting hijab is a sign of them wanting the system to change fundamentally,” Momeni said.

The 2009 protests were led by Iran’s “reformist” movement which called for a gradual opening-up of Iranian society. But none of Iran’s political parties — even the most progressive, reformist-led ones — supported abolishing the compulsory veil.

Shams, who grew up in relatively religious family and sometimes wore hijab, recounted how during the 2009 protests, she renounced the headscarf publicly. She found herself under attack by pro-government media, but also shunned by figures in the reform movement — and by her then-husband’s family.

“The major reason for our divorce was compulsory hijab,” she said.

As Iran has been besieged by U.S. sanctions and several waves of protests fueled by economic grievances, the leadership has grown insular and uncompromising.

In the 2021 presidential election, all serious contenders were disqualified to allow Ebrahim Raisi, a protégé of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, to take the presidency despite record low voter turnout.

The death of Mahsa Amini, who hailed from a relatively impoverished Kurdish area, has galvanized anger over forms of ethnic and social — as well as gender — discrimination, Shams said.

From Tehran’s universities to far-flung Kurdish towns, men and women protesters have chanted, “Whoever kills our sister, we will kill them.”

Shams says Iran’s rulers have backed themselves into a corner, where they fear yielding on the veil could endanger the 44-year-old Islamic Republic.

“There is no way back, at this point. If the Islamic Republic wants to stay in power, they have to abolish compulsory veiling, but in order to do that they have to transform their political ideology,” she said. “And the Islamic government is not ready for that change.”

Copyright 2022 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.