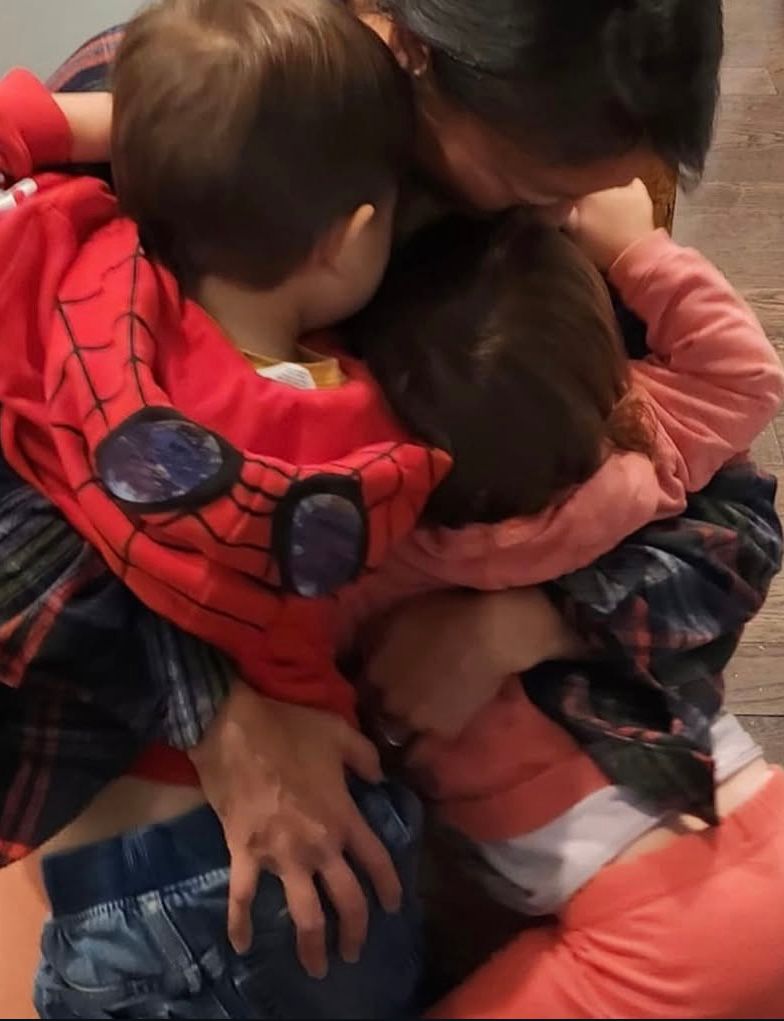

“Becoming a new mother in May 2020 was really, really actually awful,” said Stephanie Wu.

Wu and her husband welcomed their first child in the midst of the COVID-19 lockdowns.

“My parents masked up and met our son on the sidewalk outside the apartment,” Wu said.

The chaos of that time was especially hard for the new mom.

“When my son turned one year old is kind of when I was just like, ‘Oh my God, what happened to my life?’”

Five months later, Wu found out she was pregnant with her second child. Soon after giving birth to a healthy baby girl, she noticed signs that she was struggling.

“I had periodic insomnia still,” she said. “I think all of that, it was sort of like the cascade.”

She was overwhelmed by intrusive thoughts, one of the many symptoms of more serious perinatal mood and anxiety disorders, or PMADS.

“I just kept having just such despair, just like the most profound despair of my life,” Wu explained.

PMADs include mental health issues ranging from pregnancy through postpartum – including depression, obsessive compulsive disorder, anxiety, bipolar disorder, post- traumatic stress disorder, and in the most serious cases, postpartum psychosis.

Many times, new parents struggling with their mental health display symptoms indicating one or more of these illnesses, but they are dismissed as normal amidst the stressors of parenthood.

“There's a certain amount of anxiety that's Darwinian and important so that we care for this kind of helpless, dependent creature,” said Dr. Catherine Birndorf, a reproductive psychiatrist and the co-founder of the Motherhood Center of New York. The Motherhood Center offers treatment for expecting moms and birthing people experiencing mood and anxiety disorders.

“People often ask for what's normal and what's not,” said Birndorf. “Like, how do you know when you've kind of gone over the line?”

She outlined some of the ways women can identify when it’s time to seek help.

“What's never normal is hopelessness, guilt, you know, intrusive, violent thoughts telling you that something bad could happen,” she explained.

“Suicidality, never normal,” she said. “Feeling like you want to escape your life.”

These symptoms were familiar to Wu, who has sought treatment at the Motherhood Center.

“I was feeling very, very suicidal for a lot of my worst periods,” she said. “I like, I think that if I didn't have kids, I could have maybe gone to a darker, like I could have, I don't know how to call it, gone further.”

Although traumatic, Wu’s experience is not a rare occurrence.

“Mental health conditions are actually the most common complication of pregnancy and childbirth. They impact at least one in five people either during pregnancy or that first year following pregnancy,” said Adrienne Griffen, the Executive Director of the Maternal Mental Health Leadership Alliance. It’s a national organization that advocates for more support for mental health issues throughout pregnancy and postpartum.

After struggling with postpartum depression herself, Griffen knows the importance of finding help.

“We don't do enough to support new mothers in our country,” she said. “We don't do enough to support new parents and new families.”

It’s a growing concern. Last summer, the Surgeon General issued an advisory citing parental stress as a public health issue.

For those experiencing perinatal mood and anxiety disorders, the distress is compounded by limited access to treatment.

“The vast majority, as many as 75%, get no treatment whatsoever, and that leads to potential long-term implications not only for the mom, but for the baby and for the family,” Griffen said.

For some, it can overflow into deadly territory.

Suicide and overdoses account for nearly a quarter of maternal deaths in the United States, according to the CDC – trumping the second-leading pregnancy-related cause of death, hemorrhaging, by nearly ten percentage points.

Black women are especially vulnerable; they experience maternal mental health symptoms at nearly twice the rate of all women and are less likely to get help. It’s a maternal mental health crisis; one that until recently has been largely under the radar. But why?

“There is this pervasive fear in our country that if you are to share how you feel and it’s negative and you’re a mother or pregnant person, you’re bad. I could just scream.”

Dr. Birndorf cites a myriad of reason new mothers may not seek help – among them, fear of the stigma attached to mental health issues.

“People are judgmental, and I don’t want them to treat me differently,” said Janelle Jones, a mother and past patient of the Motherhood Center.

Jones was aware she was experiencing mental health issues after she gave birth to her second child.

“I was easily very irritated, and I would have rage sometimes when it didn’t make sense,” Jones said.

She hesitated seeking treatment out of fear that she could lose what was most important to her.

“There’s not a lot of talk about it, and it’s a big stigma,” she explained “You might get your children taken away.”

Breaking through that stigma to access care is a monumental task for caregivers and patients alike.

“You are not bad,” Birndorf says. “You are having difficult feelings.”

For the our second report in this series, watch here: Advocates push for expanded access to maternal mental health treatments