This story is part of Spectrum Bay News 9 and Spectrum News 13's special reporting on the coronavirus pandemic in Tampa Bay and Central Florida. Join us at 7 p.m. Thursday, March 11, to watch "A Year of COVID" on Spectrum Bay News 9, Spectrum News 13, or the Spectrum News app.

You can catch a special encore of the entire special at 4 p.m. Saturday, March 13, 2021 on Spectrum Bay News 9 and Spectrum News 13.

The entire program also can be viewed on our app and website. Watch the first segment above, then click here to continue watching.

FLORIDA — When it happened, it happened fast.

On March 1, 2020, just two days after the first recorded death on American soil from a mysterious new contagion emanating from China’s Wuhan province, two Floridians tested positive for the coronavirus—an elderly man in Manatee County who had been in contact with an infected individual, and a young woman in Hillsborough who’d recently returned from abroad. The following day, the Florida Department of Health issued a few vague preventative guidelines, such as avoiding overseas travel to certain areas.

Three days later, Florida saw its first two deaths, in Santa Rosa and Lee counties.

Within a week, Governor Ron DeSantis had declared a state of emergency. Grocery stores were limiting purchases as residents hoarded toilet paper and hand sanitizer, and cruise ships with positive test cases aboard anchored offshore, unable to come into port. Masks began to appear on some, while others clung to the idea that the emerging crisis was either a hoax or really no big deal.

On March 13, Disney World and Universal Orlando announced they would close in two days—a particularly ominous turn of events for Florida—as the state decreed that public schools’ spring breaks would be extended by one week. Less than a week after that, bars and nightclubs statewide were ordered closed, and all live events scheduled through at least May had been canceled or postponed.

By March 19, those schools with the infrastructure already in place, mostly colleges, were moving toward online-only classes. The State of Florida had just more than 430 recorded cases of COVID-19.

By March 22, that number had climbed to more than 1,000.

That’s how quickly the Sunshine State plummeted into the darkness of the coronavirus pandemic. And here we’ve remained, surviving in the shadow of a once-in-a-century global catastrophe, for an entire calendar year. As a state dependent upon tourism and our service industries, Florida has been harder hit than most. We’ve seen our routines, our jobs, and our relationships upended. We’ve endured economic devastation, bureaucratic ineptitude, and countless familial tragedies. We’ve been forced to rethink our very lives and the way we live them.

Now, vaccines are rolling out (albeit with plenty of snags, controversy, and wildly varying degrees of efficiency). People are eating inside restaurants again. Theme parks are open. There are signs that Florida may be returning to some semblance of normalcy in the foreseeable future.

But that doesn’t mean it’s over. And even if and when it is, no one who lived through it will ever forget the profound—and profoundly traumatic—events of the COVID-19 pandemic’s Year Zero.

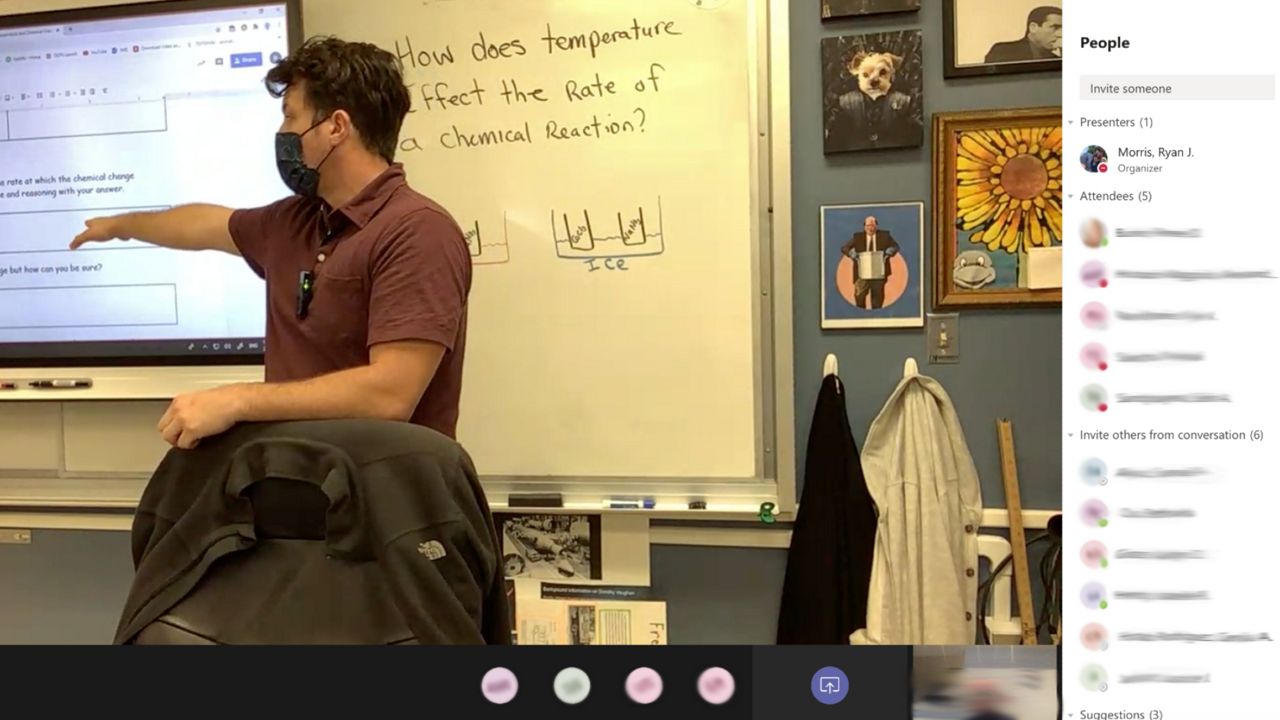

Education upheaval impacts students, families

One year later, the debates continue: Should schools remain open during the pandemic? Does face-to-face instruction pose a significant risk to students and teachers? Does online learning impede a student’s progress?

Those questions began to arise after March 13, the day that Florida Education Commissioner Richard Corcoran recommended that all state school districts take an extra week of spring break.

That meant that students and teachers wouldn’t return to school until March 30. That date got extended to mid-April.

The ensuing months would bring upheaval. That came from the April closing of public schools and reliance on distance learning for the rest of the 2019-2020 school year and, as the pandemic raged, the reopening of schools in the fall with distance-learning options.

The closing of schools created challenges for students who lacked laptop computers, and it introduced technical and connection issues to some students who had them.

The closures had dramatic effects on working parents, who now had to juggle work and the educational supervision of their children. The decision took an especially heavy toll on parents of special-needs children, including those on the autism spectrum.

“When you tell an autistic child to stay home,” said Leesburg resident Josh Parisoe, father of an autistic child, “you’ve now given the parent a full-time job.”

The switch to online learning raised questions about the quality of learning, and it prompted concerns about children who had relied on school meals. The latter would prompt school districts to use federal funding to distribute free meals to children age 18 and under through the school year.

For a lot of children, school offers “the only opportunity for fresh fruits and vegetables and low-fat proteins,” said Lora Gilbert, senior director of Food and Nutrition Services at Orange County Public Schools.

The fall reopening of schools brought new concerns and challenges. Chief among them: how to make classrooms safe for teachers and staff and for students who chose to return to face-to-face instruction.

The question of safety prompted a lawsuit from the Florida Education Association, which demanded safeguards to combat the virus. The FEA eventually would file a “notice of voluntary dismissal” of its case against Gov. Ron DeSantis and Education Commissioner Corcoran, among others.

In other action over the return to face-to-face learning, the United School Employees of Pasco filed a lawsuit against Pasco County Schools, and the Orange County Classroom Teachers Association sued Orange County Public Schools. Online court records last week showed the cases as open and pending, respectively.

The Florida Department of Education directed school districts to work with county health departments on safety protocols, including mask and distance requirements.

In July, some parents found themselves struggling with the question of whether to keep their kids learning at home or send them back to physical classrooms.

"It’s a very, very difficult decision," said Hillsborough County resident Yasmine Badawi. "But then 30 minutes later I’ll tell you I don’t care if my kids pass or fail this year. I want my kids alive."

Schools in Tampa Bay and Central Florida implemented quarantine requirements for those exposed to COVID-19.

They’d also mourn COVID victims and salute pandemic-era heroes.

Rosemary Collins, 51, a music teacher at Clearwater High School, died suddenly in December after testing positive for COVID-19, family members said. People who knew her called her an inspiration.

"It's a shame that her worst nightmare happened," her daughter, Lindsey Collins, said at the time.

In the fall, meanwhile, Ida Shuler left her teaching position at Ippolito Elementary School in Riverview, then bought a small bus with savings and donations. She created a mobile classroom in which she would go from neighborhood to neighborhood and provide free tools and support to online students.

Of the pandemic, Shuler said, “I don’t want this to be another burden on families. We’re going through so much as it is.”

Some schools reacted to the effects on students who learned from home. In Volusia County, officials said in October that students in its Volusia Live online learning program would have to return to the physical classroom if they scored a D or F in any class that quarter.

Late last year, Gov. DeSantis said schools would remain open during 2021, with a continued option to learn from home.

In an emergency order, Education Commissioner Corcoran required schools to alert parents if their children weren’t making “adequate progress” in an “innovative learning modality” such as online. The order required such children to return to face-to-face instruction in January unless their parents disagreed.

Spectrum News early this year observed a hybrid online/in-person class from the perspective of an eighth-grade student at Orlando’s Windy Ridge K-8. It provided a glimpse of the challenges for students and teachers alike.

“It’s pretty good,” student Vaishali Salecha told Spectrum News about online learning. “What I like is that I can focus without distractions that I could have in class, like people talking in the background. But online it’s a little trickier because sometimes the Wi-Fi goes out, and it’s not as interactive as when you’re in class.”

Her father, Rajendra Salecha, said he preferred in-person instruction for his daughter and for a son who attends Orlando’s Olympia High School. That would give them “a much better learning environment, and the teachers wouldn’t have to worry about this dual kind of learning mode.”

“But at the same time,” he said, “the risks with COVID are still there.”

Teachers continued to emphasize the risks to them, pointing out that they worked indoors and in small classrooms with dozens of students for hours at a time. The Florida Education Association urged DeSantis to give teachers stronger consideration for COVID-19 vaccinations.

"Considering so many of us are in that situation, it's just not healthy," said Tampa teacher Julia Spalding. "We're at a higher risk of getting the disease, and possibly dying."

In early March, DeSantis expanded Florida’s vaccination program to include law enforcement officers, firefighters, and K-12 teachers age 50 and over.

Orange County Public Schools teacher Amy Modesto expressed excitement at the prospect of getting vaccinated.

About the pandemic, she said, “It still does frighten me for my children.”

Tourism: “If we don't get people back to work quickly, it's all over"

As the pandemic goes, so goes tourism. And as tourism goes, so goes Central Florida.

Tourism supports a reported 41 percent of the region’s workforce. And Central Florida’s theme parks—especially Disney World, Universal Orlando, and SeaWorld Orlando—drive the region’s tourism.

The pandemic prompted the three parks to close shortly after the pandemic hit in March, then to announce indefinite closures that lasted until June for SeaWorld and Universal Orlando and July for Disney World.

The closings contributed to major revenue losses for the park’s parent companies and created a domino effect of knocked-over businesses that included bars, hotels, retailers, and restaurants.

Early May brought Phase 1 of Gov. Ron DeSantis’s reopening, which allowed retail stores, restaurants, museums, and libraries to operate at 25 percent capacity. But some called for a broader reopening that addressed theme parks.

“If we don't get people back to work quickly, it's all over," hotelier Harris Rosen said in May.

With Phase 2 of the state’s reopening, the three major theme parks reopened in the middle of the year to reduced capacity and with coronavirus safety measures, but the trouble was just beginning for thousands of workers.

Universal Orlando said in June that it would lay off an undisclosed number of workers. In July, it confirmed another round of layoffs but again wouldn’t say how many.

In September, SeaWorld Entertainment laid off almost 1,900 employees at its theme parks and Orlando-based corporate office. SeaWorld cited the pandemic for its decision and said it “must transition certain park and corporate personnel from a furloughed status to a permanent layoff.”

Matthew Kellam, one of those furloughed employees, said at the time that he and others figured they would return to work and didn’t seek other jobs.

"But as soon as that layoff happened,” he said, “we're all now scrambling and looking for other jobs."

In late September, Disney announced it would lay off 28,000 U.S. employees, including workers at Disney World.

“As heartbreaking as it is to take this action,” Disney Parks chairman Josh D'Amaro wrote in a memo to employees, “this is the only feasible option we have in light of the prolonged impact of COVID-19 on our business, including limited capacity due to physical distancing requirements and the continued uncertainty regarding the duration of the pandemic.”

In late November, Disney said it would lay off an additional 4,000 workers by the end of March.

Mark Newman stood among those 32,000 workers, and his 23-year stint with the company ended in early December.

Newman went from a manager at the Disney Vacation Club to a builder of handcrafted wooden flags and a possible business. He had “so many orders I couldn't make them.”

As for the end of his Disney career, he called it, “kind of devastating, very, very sad, kind of like a chapter in your life is ending.”

Tampa Bay tourism has also faced the crippling effects of the pandemic. Following an ill-advised crush of bodies for the first part of spring break season last year, Pinellas County beaches closed on March 20, effectively eliminating some of the region’s most visible and attractive elements until they reopened with COVID protocols on May 4. By then, real fear of the pandemic had set in; locals had made a habit of staying at home, and of course, no one was flying in, sending beachside hotel and retail revenues into a tailspin.

The area’s two main theme park attractions, Busch Gardens and Adventure Island—both SeaWorld properties—closed down after shutting their doors on March 15. Busch Gardens reopened on June 11 but announced in September that nearly 1,000 furloughed employees would be permanently laid off. Adventure Island sat out its entire summer season; the park always closes for the winter and opened for the first time in nearly a year on March 6.

Local museums, including world-renowned destinations like St. Petersburg’s Dali Museum and Sarasota’s John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, likewise shut down in mid-March along with everything else. They missed out on the spring’s prime tourist season, with most staying shuttered until late June or early July.

Perhaps nowhere was the effect on Tampa Bay tourism as noticeable as it was at Tampa International Airport, consistently one of the nation’s busiest and highest rated. The airport lost a reported $5.9 million in revenue in March alone, ran at 97 percent below normal traffic in April, and by May was projecting an additional loss of $41 million through the end of its fiscal year in September.

In January, Pinellas County tourism bureau Visit St. Pete Clearwater estimated that the loss in economic impact due to the pandemic in that county alone amounted to more than $2 billion.

Unemployment falls short

By late March, the economic and psychological effects of the pandemic already reverberated throughout Florida, including in Central Florida and Tampa Bay.

“Your mind is not resting at all. It’s scary. You don’t know what’s going to happen next,” said Zeyad Elmashak, who worked at a Starbucks at Orlando International Airport until he abruptly got laid off.

Gov. Ron DeSantis said more than 6,000 businesses already had laid off more than 40,000 people – a number that would quickly skyrocket.

Florida’s unemployment rate shot up from 4.4 percent in March to 13.8 percent in April. The surge in joblessness overwhelmed call centers at the Florida Department of Economic Opportunity and crashed the DEO’s CONNECT online unemployment-benefits system.

Desperate Floridians complained of not being able to get through to DEO officials on the phone or online and of spending hours trying to apply for unemployment benefits because they were repeatedly getting knocked off the online system.

Ira Leighton, who had been an assistant manager at Salon Volo in the Pinellas County town of Kenneth City, said he applied for unemployment benefits on March 22 and that his claim hadn’t gone anywhere in a month.

“Extremely challenging, with constant error messages, being dumped, being able to get certain information in, and then having the server sort of crash,” he said.

Meanwhile, Florida’s maximum weekly unemployment benefit of $275 stood and still stands, among the lowest in the country.

Unemployed residents got additional help in the form of an additional $600 a week from the federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES, Act, which then-President Donald Trump signed into law on March 27.

Yet Floridians continued to suffer from the slow to idle unemployment-claims process, and some took to the street in protest.

That included a May caravan on Tampa’s Kennedy Boulevard. Some residents said they had run out of money and were living on credit cards and help from relatives.

"I am losing my home. I am borrowing money from family to get groceries,” said Julia Shear of St. Petersburg. “I had to go and get $20 from my daughter to go get $13 of supplies to make this sign. It's ridiculous and it’s criminal."

Because of the additional federal money, some of those lucky enough to promptly collect jobless benefits—particularly those in low-paid service jobs—found themselves making more money on unemployment than what they had been making on the job.

As a result, some business owners said they had trouble finding workers when business picked up, creating another economic effect.

“We have all the product ready to go; we just have no drivers,” Mitch Ruiz, owner of Barnes Supply in Orlando, told Spectrum News in May.

The $600 federal supplement ended on July 31, less than two months before Gov. Ron DeSantis signed an executive order that allowed bars and restaurants to open at full capacity. Those events created an increased demand for bartenders, servers, and other low-wage jobs and more for people who were willing to take them.

As the pandemic raged on and Florida surpassed 500,000 COVID-19 cases, the state’s unemployment rate fell from 11.4 percent in July to 7.3 percent in August. It continued to drop through the end of the year as DeSantis pledged to keep the state open for business.

“I think everybody needs to be optimistic right now,” John Flanagan, CEO of CareerSource Tampa Bay, told Spectrum News in early September. “There's a lot of employment available for folks that are looking.”

As the state stayed open, public officials put measures in place to stop the spread of the pandemic, at least at the local level. Orange County, Tampa and St. Petersburg would begin to cite bars, restaurants and other businesses that failed to comply with coronavirus safety protocols.

Meanwhile, Floridians continued to struggle.

In September, many residents complained that the state still failed to provide full unemployment benefits. And an exclusive Spectrum News/Ipsos poll in October found that only 40 percent of Florida respondents agreed that they felt better about their personal financial situation than they did before.

“Right now, nobody’s doing well,” Orlando business owner Emerson McClain told Spectrum News at the time. “I mean, wealthy people are doing well.”

Many non-wealthy Floridians struggled to keep or stay in their homes.

Officials at the Coalition for the Homeless of Central Florida said in late September that 42 percent of the people who had sought shelter there since early August declared themselves homeless for the first time.

Shelter officials told Spectrum News at the time that they braced for October 1, the expiration date of DeSantis’s moratorium on evictions and foreclosures.

But as that moratorium expired, residents got help from at least two U.S. government programs: a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention moratorium on evictions through December 31 and a CARES Act plan that allowed about 70 percent of U.S. mortgage holders to request and receive forbearance—a pause in payments—for up to 12 months.

Renters also received options for assistance from counties such as Pinellas and Orange, both of which offered eviction-diversion programs.

Still, the threat of home loss loomed. A Spectrum News report in December said landlords had obtained more than 800 writs of possession—court orders that landlords can seek to evict tenants—in Hillsborough County since August.

A similar number had been issued in Pinellas County, said William Kilgore of the St. Petersburg Tenants Union.

Also, a U.S. Census Bureau survey revealed in November that Florida held the highest percentage of adults who were somewhat likely or very likely to face eviction or foreclosure within two months.

It all came down to income and jobs, and the federal government came through with no further supplements to jobless benefits.

In the middle of November, some people still said they’d been waiting months to receive all benefits owed to them. That came amid a pledge from Dane Eagle—the third state official to oversee the state unemployment system in 2020—to make permanent fixes to the system.

“It’s very challenging. Nobody there seems they want to help,” said Marc Navarro, who was laid off from his job at Walt Disney World after six years. “The struggles I’ve gone through … not eating for weeks, almost getting evicted.”

Vaccines: A glimmer of hope

The race was on.

As the coronavirus claimed lives, spread heartbreak, shattered livelihoods, spawned stories of death and near-death, and changed the way we lived, the Trump administration last spring launched Operation Warp Speed, which sought development—and fast—of a vaccine that would slow down and eventually end the pandemic.

Pfizer said it already had been at work on one and, with BioNTech, emerged as the first to deliver – producing a COVID-19 vaccine that in December received emergency-use authorization from the U.S. Food & Drug Administration.

The news sparked elation, perhaps especially at health care organizations, from Satellite Beach and Winter Garden to Pinellas Park and Temple Terrace.

“This is truly a historic moment,” Tampa General President John Couris said at a December news conference. “This is 20,000 doses of hope. This is the beginning to the end. This is monumental if you’re sitting in our shoes.”

Yet the announcement – and one shortly thereafter about approval of a similar two-dose vaccine from Moderna -- produced almost as many questions as doses:

Who would get it first? What are the side effects? How would the vaccine get distributed? How long would it take to vaccinate everybody? How much would it cost? Do we need to continue wearing a mask after getting vaccinated? Can we see our children and grandchildren after getting vaccinated? When can our lives return to normal?

And perhaps most notably: Is the vaccination safe?

Health care officials went on the offensive from the start, declaring the vaccine safe and effective and saying that, unlike other vaccines, nobody would be injected with the virus.

“What it’s doing is stimulating your immune system to make a response and kind of trick the cells into becoming and looking like the virus and kind of engaging your whole immune system,” said Dr. Deepa Verma of Clearwater-based Synergistiq Integrative Health.

“It's a really novel way to do it,” said Dr. Neil Finkler, AdventHealth’s chief medical officer for acute-care services in Orange, Seminole, and Osceola counties. “And quite frankly, I believe that we're at the watershed moment of how we're going to look about how we treat things moving forward.”

As Gov. Ron DeSantis prioritized front-line health care workers, people in long-term care, and people 65 and over, health care leaders emphasized two critical terms: herd immunity and vaccine hesitancy.

In order to achieve herd immunity, which happens when a large percentage of a population becomes immune to a disease and makes the spread of that disease unlikely, officials needed to do something about vaccine hesitancy, or the delay of refusal of vaccines.

Government and health officials throughout Tampa Bay and Central Florida noted vaccine hesitancy particularly among Blacks, who like Latinos and other minority groups were dying from COVID-19 at disproportionately high rates.

Some pointed to U.S. history, including the deadly 40-year-long Tuskegee Study, as a reason for hesitancy and mistrust among Blacks.

Officials sought the help from houses of worship, which would provide neighborhood outreach and serve as vaccination centers.

“We’re losing too many African Americans and minority people because of this virus that we need to follow suit and get vaccinated,” Eugene Scott told Spectrum News during a vaccination event at Bethlehem Progressive Baptist Church in Hernando County.

Officials also worked to get vaccines into other underserved communities and to people who lacked online access to register and transportation to get the shot.

In three months, the federal government’s vaccine distribution-program -- which now includes Johnson & Johnson’s one-dose vaccine -- has grown into an all-hands-on effort that involves CVS, Publix, Walgreens, Walmart, and Winn-Dixie, plus community parks, college parking lots, and football stadiums, among other places.

It also involves firefighters and U.S. military members, the latter of whom are giving shots seven days a week at federally supported sites in Tampa and Orlando.

And as supply has increased and fewer seniors have shown up for vaccinations, the Orlando site -- at Valencia College West -- found itself in recent days appealing to the public to fill available slots.

It marked a sharp turn from the first several weeks of the state’s vaccination program, which throughout Tampa Bay and Central Florida saw low supply, high demand, long lines, booked online appointments, frustration, despair, and questions about when the next shipments were coming.

In early January, for example, some seniors spent the night in line for a chance to get vaccinated at Volusia County’s Daytona Stadium.

When the site reached capacity and closed, Edward Bailey remained in line in his car, six miles away.

"I'd like to see my grandkids, spend time with them,” he told Spectrum News. “I hope I can get the next shot soon so I can see the rest of my family.”

In early March, more and more residents found themselves poised to do that.

"Think about where we were in January,” said U.S. Rep. Val Demings of Orlando. “To have three vaccines in a short period of time available is just almost a miracle.”

Looking forward: We will get through this...

As she looks ahead, Kelly Stuart Williams looks back. She reflects on the mid-1980s when various business owners along Tampa’s Dale Mabry Highway expressed concern that prolonged construction work to widen the highway would deeply hurt their businesses, as a similar project had done along Waters Avenue.

Those Dale Mabry business owners worked with the Florida Department of Transportation to ensure the road project would be completed at night while businesses were closed, Williams says – saving their livelihoods and leading to the Carrollwood Area Business Association, or CABA.

“So, a bit of our culture is that we adapt really quickly to adverse situations,” says Williams, who counts her business, Pegasos Public Relations, as a CABA member.

Williams thereby expresses optimism for the organization and its 300 or so members. As such, she stands among many Tampa Bay and Central Florida business owners and community leaders who see light emerging from the coronavirus pandemic.

They generally cite positive numbers in terms of coronavirus cases and COVID-19 vaccine supply, now from three manufacturers.

Much of the excitement involves K-12 schools after the Biden administration last week prioritized teachers and school staff of all ages for vaccinations. It brought relief to educators and school workers who found themselves at risk from working in close quarters with dozens of students at a time.

Even amid the optimism, health and government officials have sought to ease confusion over differences in vaccination eligibility at state and federally supported sites.

Officials throughout Tampa Bay and Central Florida also continue to emphasize safety protocols including mask-wearing and social distancing. Just last week, the Pinellas County School District reached a deal with teachers on pandemic rules, including on students who repeatedly refuse to wear masks.

Meanwhile, government leaders continue to move to speed up vaccinations.

President Joe Biden said last week that the U.S. would produce enough vaccines for every adult in the U.S. by the end of May. The momentum continued Monday, as Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis said residents age 60 and over would be eligible for vaccinations beginning next week as the demand from older residents decreases.

Also Monday, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said Americans who have been fully vaccinated could gather in small groups with other vaccinated people without social distancing or wearing masks. That’s perhaps a sign that mask-wearing and social distancing eventually could avoid “new normal” status.

Even before this week’s announcements, Orlando Mayor Jerry Demings told Spectrum News: “I’m optimistic about what we’re seeing. Our numbers are declining daily of new cases. The number of people who are being vaccinated is increasing. The available supply of the vaccine that is flowing into our community is increasing.”

Demings emphasized efforts to get the vaccine into underserved communities and said he was “very encouraged by recent dialogue with our federal partners, our state partners, and our other local partners to mitigate the disparities that have occurred.”

For many, the way ahead depends on action from Congress and the ability to find a job. President Biden this week is expected to sign a $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief bill that would include funding for vaccines, the reopening of schools, unemployment benefits, and direct payments to Americans.

Demings said Monday the county stood to receive “as much as $251 million in federal recovery assistance” from the plan, which portends similar federal assistance for other large counties such as Hillsborough and Pinellas.

“That will go a long way to helping our community recover,” Demings said.

The Tampa area’s unemployment rate stood at 5.2% in December, down from 13.2% in April, with the Orlando area’s rate at 6.9% in December, down from 21.1% in May.

The sharp drops ignore that the tourism- and services-focused regions lost a combined 170,000 private-sector jobs last year, according to the Florida Department of Economic Opportunity.

But positive economic signs have appeared. An official at TradeWinds Island Resort on St. Pete Beach told Spectrum News last week that the hotel had a 98% occupancy rate for the month and that it needed to hire up to 100 employees.

In another sign of optimism and return of tourism, Universal Orlando revealed last month that a new Universal Studios Store would open at the theme park.

Outside the tourist areas and theme parks, the same positive outlook persists.

“People are spending, and our business is increasing,” Jay Patel, owner of an Orlando 7-Eleven and vice president at the Central Florida-based Indian American Business Association & Chamber, told Spectrum News 13. “People are coming back into downtown, so I’m looking at it like it’s going to be a great future.”

Not everybody’s convinced. Abdul Tharoo, founder of Tharoo & Co., a family-owned and -operated jewelry store, said last month his business saw a 70% to 75% drop in revenue from the previous year after the nearby Orange County Convention Center lost business because of the coronavirus pandemic.

He noted problems for owners of retail stores even if tourism returns.

“Amazon really took over the market, and now the consumer has become so comfortable sitting in their bedroom and ordering things,” Tharoo told Spectrum News. “They don’t want to go shopping. The malls are deserted. There’s no shopping.”

If the shopping isn’t hot, the real estate market certainly is.

Reports continue to show extremely tight housing supply in Tampa Bay and Central Florida, resulting in increased prices for buyers and renters. Realtors say that’s in part due to the pandemic, which throughout the country has turned homes into workplaces.

“So, I think they say, ‘We're going to pick up and we're going to move to Florida. We can have great weather. We don't have to shovel snow,’” Ellie Lambert, a licensed real estate broker and president of Greater Tampa Realtors, told Spectrum News. “Employers don’t even really know whether they’re still living in Kalamazoo or Tampa.”

Lambert expressed concern for some homeowners who requested and received forbearance – a pause in payments – for up to 12 months if they faced financial hardship during the pandemic.

Some homeowners mistakenly believe that forbearance removes any future obligation to make payments, she said. She pointed out that they’ll get a surprise if they try to sell their home and find that the mortgage lender added their paused payments to the back of their mortgage, as lenders often do.

Struggling homeowners think, “‘I'll file forbearance, and then they're going to forgive that,’” Lambert said. “It’s not forgiven by your lender, so I think that has caused some confusion.”

Another question remains – whether scores of offices will shut down for good now that businesses and workers have become accustomed to working from home.

Carrollwood Area Business Association President Jennifer Jenkins, founder of Rooted Holistic Health, told Spectrum News she has heard business owners discuss the cost and time savings of having employees work from home.

“I've also heard the flip side, where others can't wait to get back because they love the human interaction,” Jenkins said.

She said she thinks businesses also have found comfort and efficiency in digital networking and communications and would continue to rely on video conferencing, for example.

“I don’t think anything will ever replace” in-person communications, she said. “But being able to offer both, I think, is going to be extremely important.”

Jenkins and CABA’s Williams mentioned a food pantry in Carrollwood whose clientele grew dramatically upon the onset of the pandemic and the layoffs it brought. The business association raised over $8,000 for the food pantry, Williams said.

“We have seen some people who had never, ever struggled before who have lost their jobs, who are now leaning on support from the community food pantry and needing a helping hand,” Jenkins said. “It is a bad time, without a doubt, for a lot of people. But what makes it good is the good of the community coming together … and that together we will get through it.”

)