TALLAHASSEE, Fla. — Two hotly contested bills about race and gender lessons in Florida public schools are one step closer to becoming law.

Both pieces of legislation — commonly referred to as the "individual freedoms" or critical race theory and "parents rights in education" or "Don't Say Gay" bills — have generated a lot of debate from both sides.

What You Need To Know

- State House lawmakers passed 'Don't Say Gay,' Critical Race Theory-limiting bills

- The House passed the bill on a party-line vote; bills now move to GOP-controlled Senate

- PREVIOUS STORY: Lawmaker withdraws amendment to 'Don't Sat Gay' bill

- What is critical race theory? An explainer

State lawmakers in the Florida House passed legislation that aims to limit instruction on sexual orientation and gender identity in school, and another measure backed by Gov. Ron DeSantis that ensures that critical race theory isn’t discussed in public schools.

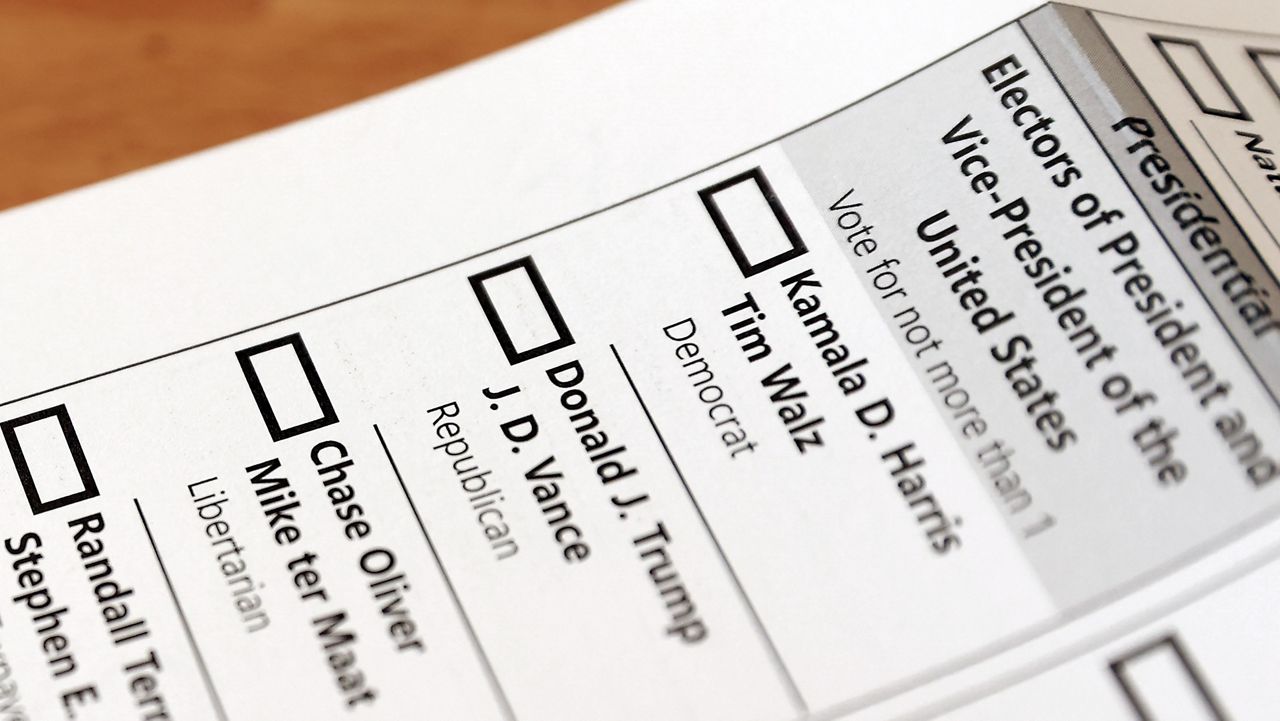

The bill, called "Don’t Say Gay" by its critics, would prohibit school districts from having an organized discussion about gender identity and sexual orientation among students.

The House passed the bill on a party-line vote (69-47), with most Republicans in support. It now moves to the GOP-controlled Senate.

“It sends a terrible message to our youth that there is something so wrong, so inappropriate, so dangerous about this topic that we have to censor it from classroom instruction,” Rep. Carlos Guillermo Smith, a Democrat who is gay, told lawmakers in the House before the measure passed.

But supporters said that the measure simply gives the power to parents on dealing with such sensitive issues.

"I believe the fundamental question is who has the responsibility, who should be charged with instilling values in our children?” said State Rep. Robert Brannon (R) House District 10. “I just believe primarily, it should be parents.”

The senate appropriations committee is poised to take the house version of the "Don’t Say Gay" bill on Monday.

Dealing with critical race theory in the classroom and workplace

Meanwhile, teachers and business would be limited on how they can discuss racial issues in classrooms and employee training sessions under a bill the Florida House passed Thursday over the strong objection of Black lawmakers.

Proponents said the bill, pushed by DeSantis, simply states that teachers and businesses can’t force students and employees to feel they are to blame for racial injustices in America’s past.

Opponents said the legislation was designed to create racial division for DeSantis’ political benefit and would have a chilling effect on the discussion of injustices past and present. Black lawmakers said it is designed to make whites more comfortable about racial issues.

“This is for the governor, and by the governor. Whose life will this bill change for the better?” said Democratic Rep. Tray McCurdy, who is Black. “This bill is a joke. We fight against mask mandates, yet we want to mandate masking history.”

The bill passed on a 74-41 party line vote. A Senate version of the measure is expected to be heard in its final committee stop next week before being considered by the full chamber. Differences would have to be worked out before the session ends March 11.

Understanding Critical Race Theory

Critical race theory is a way of thinking about America’s history through the lens of racism. It was developed during the 1970s and 1980s in response to what scholars viewed as a lack of racial progress following the civil rights legislation of the 1960s. It centers on the idea that racism is systemic in the nation’s institutions and that they function to maintain the dominance of white people in society.

The bill reads in part, “A person should not be instructed that he or she must feel guilt, anguish, or other forms of psychological distress for actions, in which he or she played no part, committed in the past by other members of the same race or sex.”

The bill was amended on Tuesday to require the expansion of the teaching of Black history, including teaching students about the ramifications of prejudice, racism and stereotyping.

In a phone interview before Thursday’s House session, Rep. Fentrice Driskell said the amendments still didn’t make the overall bill palatable.

“This bill is not redeemable,” said Driskell, who is Black. “It suppresses the truthful and accurate teaching of history. ... My concern is that we are telling teachers to do their job while also tying a hand behind their back and trying to keep things in parameters of how a child will feel.”

Information from the Associated Press was used in this report.