ORLANDO, Fla. — She was an education and civil rights pioneer, and on Wednesday, she was permanently honored with a marble statue installation in Washington, D.C.

But some of Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune’s accomplishments remain lesser known, including in the realm of housing.

As an adviser to President Franklin Roosevelt in the 1930s, on his “Black Cabinet,” Bethune worked to elevate the concerns of Black Americans nationwide.

One of those concerns, in addition to civil rights, was fair access to housing and loans.

What You Need To Know

- A marble statue of Mary McLeod Bethune was unveiled Wednesday at National Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol

- Bethune is the first Black American to be immortalized in National Statuary Hall

- She started a school for young black girls, was elected president of National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs and later started her own organization, the National Council of Negro Women, which still exists today

Her eldest living granddaughter, Dr. Evelyn Bethune, says her grandmother was a “game changer,” who was well ahead of her time.

Dr. Mary McLeod leveraged political relationships to lobby for and champion the cause, “not just for Blacks, but poor whites" struggling to find a place to live.

“Because of the status my grandmother had, everybody wanted her to participate in whatever it was they were doing," Dr. Evelyn Bethune said. “She did things grassroots and by understanding the power of building relationships."

In 1948, one such project — Washington Shores — was heralded as a "solution to [the] Negro housing problem," per an archival document dug up by Dr. Clarissa West-White, a reference librarian at Bethune-Cookman University. The new community, off of Orlando's Orange Center Blvd., was meant to be replicated across the country as a pattern for cities to follow.

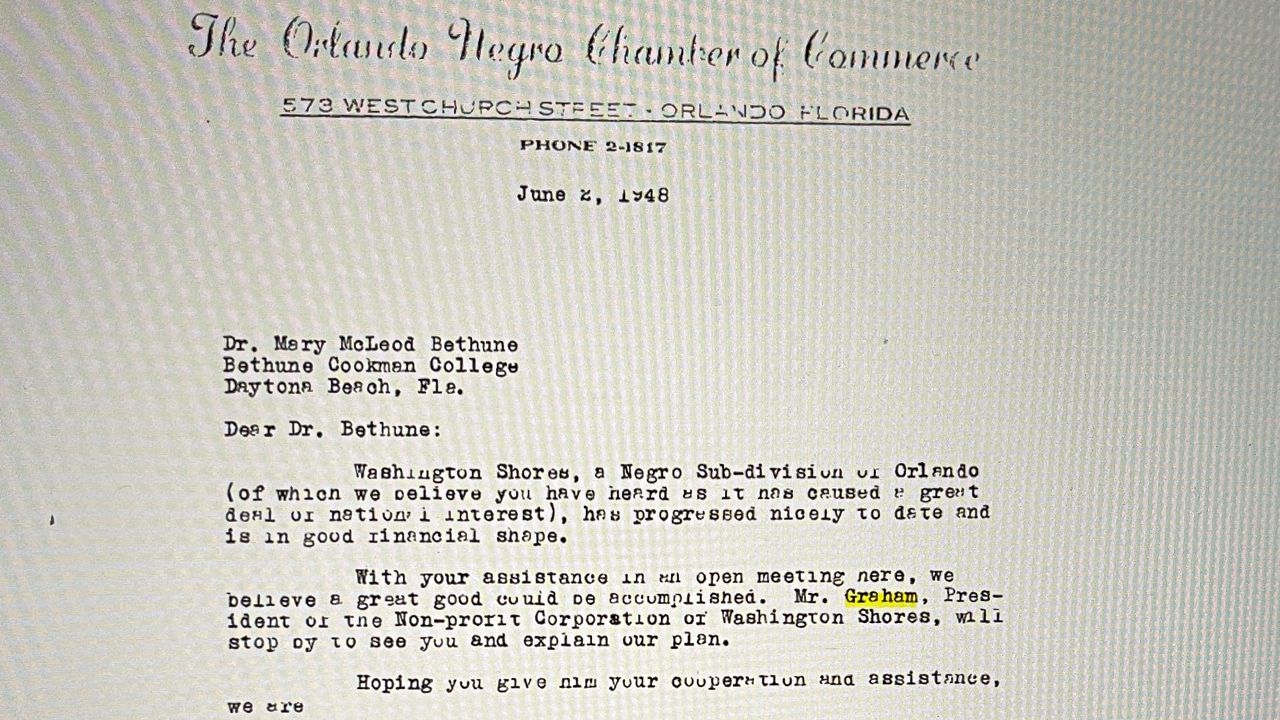

Other documents obtained by the Daytona Beach university, also from 1948, detail eager correspondence between the community itself and the Orlando Negro Chamber of Commerce, addressed to Dr. Bethune.

West-White explains that, while it’s unclear if Dr. Bethune actually met with key organizers of the Orlando development, she was certainly well aware of the project, which included government guarantees of Black homeowners’ mortgages.

Decades later, the historically Black community of Washington Shores remains a source of pride in the City Beautiful.

“It’s a love for my community and a sense of worth,” said Reverend Harry Rucker, who bought his home there in 1975. “I feel comfortable living in my own community, especially where I grew up.”

Pastor of the 132-year-old First Shiloh Missionary Baptist Church, Inc. in Sanford, Rucker lives on Bethune Drive, just blocks from two statues honoring the first Black police officers to serve the city of Orlando.

"When you come around and see a statue of these two men, it reminds us of where we come from, the trail that they blazed," he said. "It gives you a sense of, if they did it, more of us need to do it.”

And while there’s no statue of Bethune in Washington Shores, Rucker says he remains inspired by her role in ensuring fair access to housing across Central Florida.

He says the decision to honor her in marble in Washington, D.C. will help spread her legacy nationwide.

“I see her different than just representing Florida. I see her representing Black folk, and I see her crossing boundaries years ago and getting involved.”