TAMPA, Fla. — As Black Maternal Health Week continues, we're learning more about the health disparities linked to Black mothers and pregnancy-related deaths.

Spectrum News is also examining more troubling statistics a group of mothers wants to shine a light on by sharing their stories of loss.

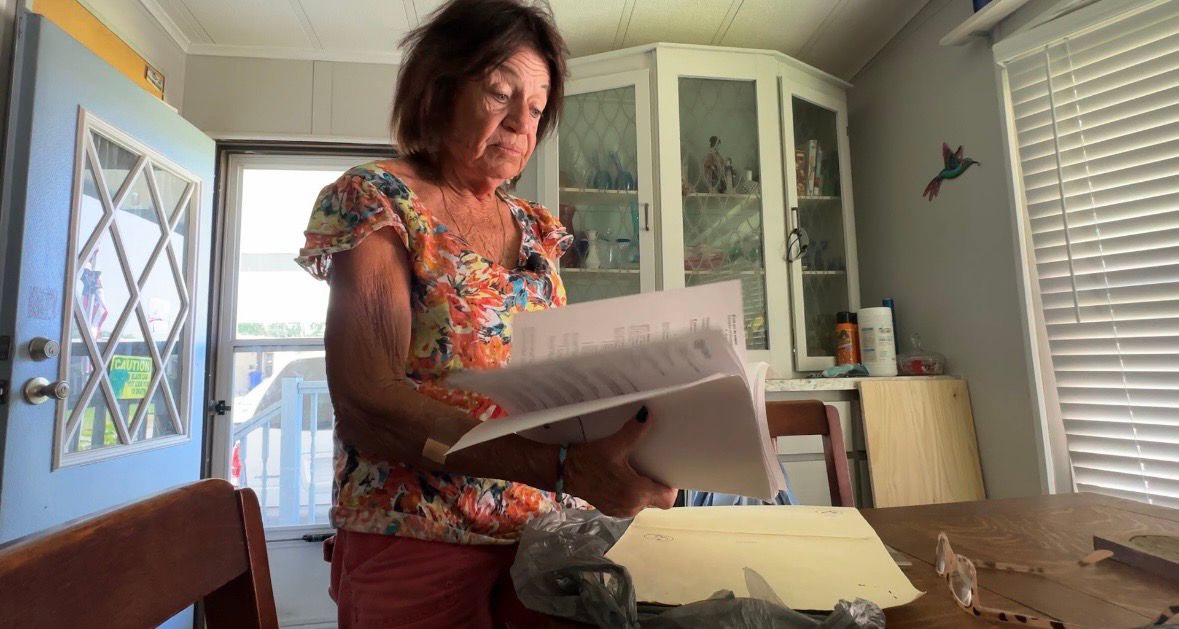

Like most moms, not only can she remember every moment, Jennifer Johnson saved everything she could when she had her first son, Malachi.

“Malachi means messenger of God, and Omari means he who is full of life,” Johnson said. “It’s hard to talk about it and not feel it. I’m there.”

The pictures of her tiny baby are a reminder he was here, too. His birth certificate — stamped with the word “deceased” — along with the void left behind, is a reminder that he’s gone.

“When the baby came out, I remember it was all very, very painful, and I remember holding my baby when he came out and they gave him to me and I held him,” Johnson said.

She says her difficult labor came too early.

“Being that I was only maybe 21 weeks (along). They said that I didn’t make it — my baby didn’t make it to the age of viability, which is 24 weeks,” she said. “That is the age they believe it’s worth the effort to try to keep the baby alive because of certain things that are already developed enough.”

Those heartbreaking moments made her turn to what she knows best — writing. She wrote poetry, essays and songs. Johnson is now hoping her tears are felt on the pages of the book, "The Mourning After" — which chronicles her son’s story, and others like it.

Amplifying the voices of mothers like Jennifer is what Xaviera Bell had in mind when she started collecting stories for her book, The Mourning After.

“For several years I had collected stories from doulas, from 17 or 18 women that had gone through the same thing that had concerns about their body that were disregarded, that had gone through multiple losses and just really wanted to have a baby on this side of heaven,” Bell said.

According to the latest data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the number of infants who died during childbirth shows dramatic differences when it comes to the race of the babies dying. Numbers show Black infants are dying at the highest rates in the United States, followed by Native Americans.

For Bell, those numbers are personal.

“At 38 years old, I was forced to have my son because they did not listen to me," she said. "My concerns were not acknowledged, and that resulted in me going into a preterm labor and I had to watch my son die April 25, 2018."

After the loss of her son Xander, Bell turned her pain into purpose by starting a nonprofit called Zeal of Xander.

She’s hoping her new book will add to her impact in efforts to reduce Black infant and maternal mortality rates.

“Those women were released from the hospital and they had a box full of things they’ll never be able to use," Bell said. "So I wanted to create a product that when Black women are released from the hospital without their children, and they will be, that they’ll have something they can use."

Bell’s work is far from over. The Black maternal health town halls she launched last year are still happening every other month, and she said she believes with the partnerships she’s making in communities, some of those deadly numbers will start to decrease.

Bell is one of the speakers at the Tampa Bay Black Maternal Health Week initiative, which is hosted by the University of South Florida College of Public Health.