Long after the end of slavery, African Americans lived under the scourge of segregation, fighting for equal treatment under the law and facing racism and oppression in everyday institutions.

But these struggles didn't just make it harder to for them to live. They also plagued the dead.

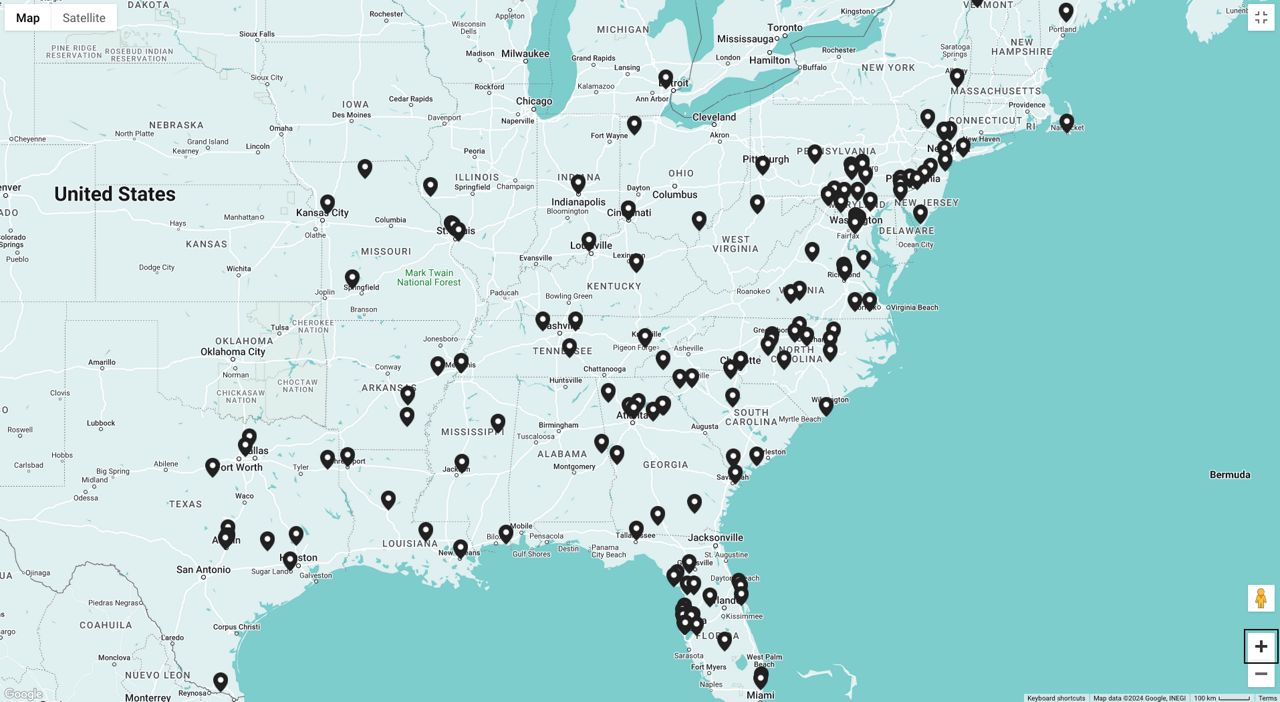

Across the United States, millions of African Americans were buried in graves that were either neglected, forgotten, or both. Land belonging to historic Black cemeteries was often sold to developers, who paved over the plots: building housing, shopping centers, parking lots, and even football stadiums.

Other burial sites were never even marked. Thousands were buried in mass graves, the identities of the dead a mystery to this day.

Now, efforts are in progress to right some of those wrongs. Organizations and local governments across the country, supported by dedicated volunteers, are working to identify the dead, relocate their remains, and bring peace to their families.

But these projects are not without challenges — from funding concerns, to upending the lives of those who were unknowingly living and working on parcels of land suddenly turned into archaeological dig sites.

Spectrum News is exploring how these plots of the past were forgotten, what's being done to honor them now, and how this injustice can be prevented from happening again.

Efforts in restoring forgotten African American cemeteries in Tampa Bay

In the last five years, the state of Florida has seen a rise in reports of erased African American cemeteries. Many attribute the conversation surrounding some of the lost cemeteries to discoveries made in the Tampa Bay area.

One of the main questions that come up: How did this happen in the first place?

Anthropologist Dr. Antoinette Jackson says she doesn’t have to see the graves to know there are likely bodies at the site of Tropicana Field in St. Petersburg, where the Tampa Bay Rays play.

“Interesting thing about this is it’s where Oaklawn Cemetery is located — or had been located — from 1906," she said. "Starting in 1906, this whole parking lot was a cemetery."

Orange cones are scattered in the lot used for game-day parking, but Jackson said the lot holds much more meaning.

“Land that is sacred. Land that was used for, at one point, that was used for the burial and recognition of the lives lived by everyday people in St. Pete,” she said. “We don’t know what happened to them.”

Three cemeteries have been located in the area around the stadium.

“Evergreen Cemetery, which was over that way, was a historically African American cemetery. Predominantly Black cemetery, segregated cemetery,” Jackson said. “Moffitt started out as a veterans cemetery, and then it was a predominantly Black one. Oaklawn was separated by race, which is this whole parking lot area."

The bodies from those cemeteries were said to be relocated more than 100 years ago, but Jackson said she had her doubts.

“The reality is that when they built in 1949, they built an apartment complex — it was called the Royal Palm Apartment Complex," she said. "At that time, during construction for that complex, they found bodies. Obviously, they hadn’t moved all the bodies."

Jackson's curiosity has led to research, and she now heads a team at the University of South Florida that look into “forgotten” African American cemeteries,

“These cemeteries were during the U.S. period of racial segregation, so Black folks were usually buried in separate cemeteries than whites, and Black cemeteries were considered marginal in relation to white cemeteries,” Jackson said.

Her team created the Black Cemeteries Network, where people report historic and forgotten African American burial grounds all over the country.

It’s a list that continues to grow. In Florida alone, there have been reports at an Air Force base, schools and businesses.

Thousands of graves have been discovered, including burials on a Clearwater school’s property, near where Clearwater Colored Cemetery (or 3C) Society President Diane Stephens grew up.

Stephens said she was born after the cemetery was gone and the bodies were said to be moved.

But she says that’s not what she saw.

“Over here is where we would play, but you would see bones coming up,” Stephens said, standing where the cemetery is located. “So, the teachers would just have you go somewhere else, and they would take care of it. We would come back out and they were no longer there.”

Ground penetrating radar confirmed what Stephens said she and so many others already suspected — human remains were found on the grounds.

“It makes me mad, really," she said. "How could people disrespect people and disregard people? Here, we’re supposed to hold human life, we’re supposed to hold it to the utmost, and yet we can disregard a person or treat them like that because of the color of their skin? That’s an injustice."

The descendants of people buried there formed the nonprofit 3C Society to raise awareness about the issue and try to right the wrongs of what happened.

So far, they’ve gotten a plaque that honors the lives of their loved ones, but Stephens said they deserve so much more.

“We said that this is not enough for the injustice they’ve done to our people," she said. "And they keep doing it."

Barbara Sorey-Love agrees. She grew up in Clearwater and witnessed archaeologists confirm the graves at the site, as well as a business property nearby. She’s part of a group that would like to see one large main burial site.

“There are a total of maybe 525 graves that are either under the building or either under Missouri Avenue,” Sorey-Love said. “For us, we’ve asked for the graves to be dug up, the remains to be dug up and brought over here. So that’s what we’ve asked for initially.”

While residents and descendants wait for word about the next steps, they’re making sure this land is treated with respect by picking up trash, and making promises they intend to keep.

Meanwhile, Jackson and her team’s research continues.

“We have names, occupations, when they died, who they were,” Jackson said. “So that’s going to make it easier to recognize and memorialize and harder to ignore, we’re hoping.”

She said what happened to the cemeteries is an injustice that she’s hoping will be made right.

North Carolina mayor searches for the dead while uncovering the Swannanoa Tunnel's history

While places like cemeteries can provide meaning and comfort to those mourning lost loved ones, some descendants of African Americans don’t have that option.

Sometimes, the lost bodies discovered didn’t belong to cemeteries at all.

For decades, the mayor of Marion, N.C., has been researching the story of the Swannanoa Gap.

In the late 1800s, railroad tunnels through the mountains were constructed by convicts and former slaves. More than 100 of them didn’t survive the grueling labor.

But the location of their remains was a mystery until just a few years ago.

“This is Jarrett’s tunnel. It is the tunnel that is the farthest east of the six tunnels that remain,” said Marion Mayor Steve Little.

He said that tunnel was dug out by hand with tools, rocks and simple explosives in the late 1800s. Remnants of the back-breaking work still remain.

And while the jagged edges of the rocks seem natural, there’s nothing natural about what happened there.

“We did not treat these people as though they were human," Little said. "We treated them worse than we treated the tools."

Today, the landscape subtly tells that horrific tale, drip by drip.

“The tears of the mountain. It’s the way I think about it,” said Little. “Crying because of what’s going on.”

Nine miles of railroad track and seven tunnels opened Asheville and the mountains up to the rest of the state. The progress may have been priceless, but the work to get there came with a hefty cost.

According to the state of North Carolina's Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, the tunnel was built by hundreds of convicts, largely former slaves arrested under unjust Jim Crow laws.

"Most of the convicts were African American (and) none had been convicted of violent crimes," the department wrote on its website.

In 1870s, the the North Carolina General Assembly leased "at least 500 convicts" to complete the work.

Little said at least 139 died during construction and were mostly just tossed aside and forgotten — until now.

“Those who were old enough to remember probably would have thought slavery was terrible, but this was worse,” Little said. “I haven’t stopped talking about it since I wrote that history paper in 1973, or whatever year was.”

A final thesis in college led Little to 50 years of research, books, and even a one-man play. But in 2020, Little felt a powerful urge to turn research into action.

By Fall 2021, Little asked town officials to have more involvement to construct a memorial to honor all the workers who built these rails.

But missing on that memorial are the names of the men who died.

“Even though you can see the other end, that’s six football fields away,” Little said.

At 1,800 feet long, the Swannanoa Tunnel is the longest, and arguably most famous, of the seven tunnels.

Crews pounded away on each side of the mountain, enduring agonizing work conditions for 18 months, until they reached the middle in 1879. And as light finally snuck through, there was a celebration for officials — and likely some relief for the convicts.

But it didn’t last long.

“Well, a few hours after the celebration of a meeting, there was a rumble and almost instantly rock fell right as the locomotive was backing into the tunnel,” Little said.

He said at least 19 convicts were killed, but their bodies weren’t sent back home.

“They needed a place to bury them, and the most logical spot was the spot just to the south of the location of the tracks,” Little said. “Right in that field is where they dug a hole and put them in, and then covered them up. Forgotten. Forgotten. No marking.

No records of their death.

No records of a burial.

Lost forever.

Or so it was thought.

In early 2022, Little, along with researchers and a dog named Abby, began searching for remains. On a foggy, cool February morning, Abby sniffed and sniffed. If she sat, it meant she detected something. After 45 minutes at the first site, Abby sat.

And the next day, she sat multiple times near the Swannanoa Tunnel, just feet from Interstate 40, where thousands of people drive by day after day, oblivious to what happened a century ago.

“I just can’t tell you how excited that makes me to know that everything that I’ve done and read and researched for 40 years is coming together, and it’s being shown to be accurate,” Little said.

Abby is trained to sense chemical changes in the soil because the chance of finding remains is unlikely.

“These convicts were so disregarded, so disrespected and uncared for that their names weren’t even written down,” he said.

But their stories remain.

A new clue arrived in the form of a state law that unsealed all kinds of records, including prison records from the 1800s.

Little scanned several old ledgers line by line, hour after hour, looking for names from the Swannanoa Tunnel collapse. But as the day ended, no luck.

But he remains optimistic as ever.

“I’m convinced there are bound to be other boxes full of papers that were never turned in," he said. "Or there’s another book, because there were only 131 convicts who were marked as dying on this project. And I know that’s low."

Last fall, researchers dedicated a second memorial near the Swannanoa Tunnel, specifically honoring the convicts who died.

“For 148 years they’ve been waiting for this,” Little said. “If you haven’t done your research, and you spent your life on this, this would still be an unknown story to most of North Carolina, right? It’s just the right thing to do.”

Fifty years into his research, Little said he’s more focused than ever to honor the men who died, and to seek justice.

“I would love it for the state to acknowledge what we did wrong," he said. "Yes, we were told by law to confine them, to punish them. But we weren’t told by the law to torture them.”

It is a 150-year-old mystery without an ending so far. But as long as Little is around, he said he will hunt for more clues.

Unfortunately, the mass grave in North Carolina isn’t unique. In 2018, in the Houston, Texas, suburb of Sugar Land, the buried remains of 95 people were discovered at a construction site for a school district.

Archaeologists found the bodies were mostly those of freed Black slaves forced to work in convict labor camps.

The school district is now taking donations to build a memorial and cemetery. The bodies were laid to rest where they were found, but the work continues to identify possible descendants.

Land sold to developer poses problems for Texas freedmen cemetery’s future

The sale of a beloved state park to a private developer is raising concerns about the fate of two freedmen’s cemeteries in central Texas.

One cemetery is well-established; the other, recently discovered.

But the uncertainty of the developers’ plans has relatives and concerned citizens fearful of the cemeteries’ fate.

When Fairfield Lake State Park, south of Dallas, was being marketed for development last year, there was no mention of its important ties to the past.

Captured in a promotional video, the glimpse of an island with “development potential limited only by one’s imagination.”

But it’s limited by something else: A private cemetery, on land once owned and still populated by the burial remains of freed slaves and their descendants, including Edward Ned Titus.

He and his wife, Clora, are buried side by side. Their children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren are also buried there, as are the descents of other freed slaves.

“All my people are there. My grandfather and my grandmother. My great uncles, and aunts,” said Hope Well Cemetery President Beverly Bass.

Passing through two gates, an old, abandoned coal power plant, and across a narrow land bridge to that developer’s island, lies the Hope Well Cemetery. Bass said power plant operators granted them access to the graves, but the new owner has not communicated with her about how the cemetery will co-exist in the middle of a private development.

“I haven’t received anything from them as of yet. I’m concerned now,” she said. “Our roots are back there. Our grandmothers and my brother, we just buried him a year ago.”

But it’s not the only freedman’s burial site that developers may have to navigate.

Freestone County historian Sandy Bates Emmons says she’s found more evidence of freedman’s graves on the recently sold land.

“It was prepared by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Cultural Resources Program in Austin, Texas, back in December of 2002,” she said.

Emmons says subsequent research indicates it was a significant discovery, appropriately noted, mapped, with even headstones photographed, located on an eastern peninsula of the Fairfield Lake State Park.

But the information was evidently ignored.

It had been 20 years since the headstone of Easter Miles had been discovered. With the property about to change hands, it was time to revisit the site.

Emmons trekked for over a mile through the forest and brush before coming upon the area that matched the photos.

“See, there’s the hand of Jesus," Emmons said while examining the site. "It points upward to the sky, and it says ‘Easter, wife of D. Miles.’ And it says, ‘Born in 1835,’ but she doesn’t know the date. And died in 1887, maybe?”

Emmons again consulted the archeologist’s study, reconfirming the importance of the site.

“The presence of a 19th century headstone, six probable grave depressions and three possible grave depressions suggest that several burials remain intact,” Emmons said. “This site is classified as a level one high management priority and should be avoided and protected.”

Emmons took photos, notes, and a tiny piece of comfort that a former slave might be the key to saving the park, as well as a piece of state’s buried past.

Spectrum News Texas made several attempts to contact the developer and state archaeologists to learn about any preservation plans for the sites. They have yet to hear back.

Burial site found under Robles Park housing complex still missing memorial

When the dead aren’t given the space to rest in peace, it’s the living that are impacted.

The work to restore lost burial sites takes time and money, and it’s rarely convenient for the people who live and work in the area.

Residents of the Robles Park Public Housing Complex in Tampa, Fla., found that out firsthand.

Not only did the discovery of a cemetery beneath the complex force them to move, but years later, there still isn’t a proper memorial.

The mystery of Robles Park Village connects residents to the hundreds of people buried underneath the public housing complex.

“The cemetery went from here, all the way down to the fence line, which led to the street, so pretty much everybody’s back door was basically a cemetery,” said Israel Aponte, a relocated resident describing the layout of the discovered burial ground.

Aponte and his sons had just moved to Robles Park when archaeologists discovered the graves — which was quite the shock for more than two dozen residents who were suddenly told they had to go. Most of them, like Aponte, were relocated by the Tampa Housing Authority.

“It was in a quick manner, because we had to be out of there within 60-90 days from the moment they told us," he said. "So it was pretty much a chaotic situation during that" time.

Chief Operating Officer Leroy Moore led the housing authority’s efforts to unearth what was underground.

“We didn’t know there were bodies interred here,” he said. “At that point, we thought they had been moved, but we knew we had a historic site.”

Today, the empty buildings, the road, the courtyard are all deemed sacred ground, with names that read like characters in a book. This place now belongs to them.

“You know, people say as long as a person’s name is spoken, a person still lives,” said Fred Hearns, a historian with the Tampa History Center.

Hearns and Moore helped form a committee to preserve the cemetery with a permanent memorial park. There’s even a design for it.

But so far, the only memorial is draped around the gate.

“This has been five years, and that’s five years too long,” Moore said.

Moore says they can’t move forward because part of the cemetery extends to two neighboring businesses. Initially, there was talk of a land swap with the city, but nothing has happened.

Tampa Mayor Jane Castor insists that at least one deal is close.

“It takes time,” she said. “It shouldn’t have taken as long as it has and we can go down a list of reasons why it’s taken so long, but my focus is on getting it done as quickly as possible.”

Until there’s a deal, there will likely be no permanent memorial.

Moore said the group can’t get the grants they need without owning the entire cemetery.

“It’s very important to call these names,” said Hearns.

Slave cemetery buried beneath a shopping center honored with memorial in Staten Island

When it was discovered that a strip mall was built on top of a slave cemetery on Staten Island, a filmmaker and descendants of those buried advocated for a memorial at the site.

Now, that is one step closer to becoming a reality.

Off a busy road on Staten Island in New York City is a strip mall with a buried past. Livermore and Forest Avenue is now Benjamin Prine Way, named after the last enslaved African American on Staten Island.

His body, along with the bodies of around 1,000 other African Americans who were slaves, is buried beneath the shopping center. It's the site of the former Cherry Lane Cemetery, where slaves were interned without headstones. David Thomas and Ruth Ann Hills are descendants of Prine.

“They were people. They were human beings, and they were discarded and mistreated and thrown away like they were nothing," Thomas said. "And that, to me, is sin."

Heather Quinlan has been working on a documentary about the cemetery. She says maps date the site to as far back as the 1800s. The property was purchased in 1954 by a real estate attorney and developer, which led to the demise of the burial ground.

“This is an injustice that needs to be addressed and corrected,” Thomas said.

Quinlan, Thomas and Hills have been pushing for recognition of the history, to honor the people whose remains are now covered in asphalt.

“Santander Bank has allocated funds and renegotiated the terms of their lease in order to create a memorial garden that will tell the story of what happened on this site, and it will include flora that has been chosen by the descendants,” said Quinlan.

Quinlan said that memorial is expected in the coming weeks. Both Hills and Thomas say they are happy the community will have a place to honor those who are buried, but they ultimately want the bodies excavated and given a proper resting place.

“There are babies here. There are families here, there are slaves here, there are freed Blacks buried here, but none of them are remembered,” Thomas said.

UCLA students use underwater archaeology to identify potential African American gravesites

Identifying historic African American gravesites can be tough. Even if the bodies aren’t beneath a building, they could be hidden behind decades of overgrown bush — or worse — entirely underwater.

Students from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) could be the future of discovering and documenting the past.

They’re diving into “underwater photogrammetry” lessons.

Their instructor is Dr. Justin Dunnavant, assistant professor of anthropology at UCLA.

“I’ve been doing archaeology on land and underwater for probably like the last 20 years now,” he said. “Exploring everything, from shipwrecks, to World War II wrecks, to plantation sites on land, to Buffalo Soldier sites as well.”

Dunnavant teaches his students how to capture video and photos for creating 3D models for an upcoming trip in underwater archaeology and marine biology.

He said due to development, there’s a lot to discover, especially underwater.

“There’s also a number of construction projects, building of highways, dams, rivers and river management projects," he said. "All of those have altered the landscape a bit. We still don’t know what all is out there."

But he says it’s critical that we find out.

“In doing underwater archaeology, we acknowledge the fact that literally millions of people died during The Middle Passage on their way from Africa to the Americas,” Dunnavant said. “And so, when we do underwater archaeology specifically around slave shipwrecks, we try to acknowledge the fact that these wrecks are not only ships and vessels, but also potential burial sites and gravesites.”

History, he says, deserves to be acknowledged.

“I tell people it’s a continuation of enslavement in certain ways," Dunnavant said. "The idea that people were essentially valued based off of their ability to labor, or their ability not to labor, continues in the afterlife, and as these areas or these lands become valuable for other purposes, or as descendants in these communities move on, they tend to be forgotten or in some cases they’re intentionally erased. And that leads to a whole series of historical facts that we need to grapple with coming into the 21st century,” Dunnavant said.

New land surveying project provides framework for cemetery database

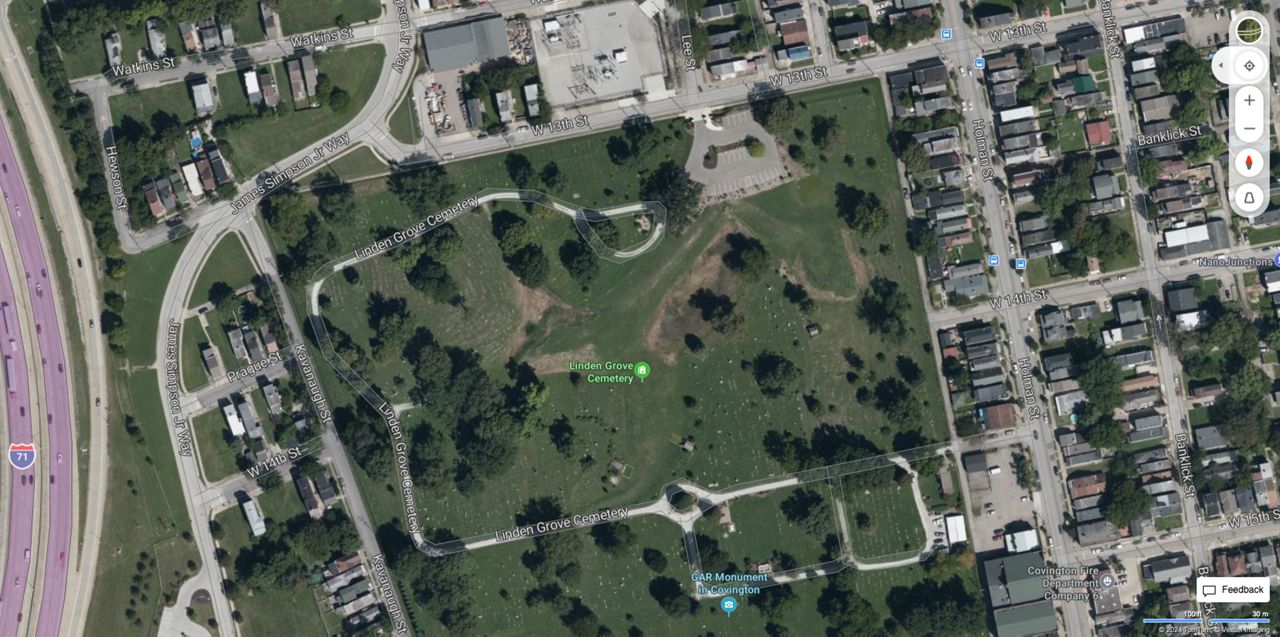

College students from a land surveying class unveiled a project that mapped out a large northern Kentucky cemetery and charted grave spaces for future reference.

Cincinnati State’s land surveying certification class has spent months mapping out half of the historic Linden Grove Cemetery in Covington.

Jennifer Townsend says finally presenting the capstone project came with a great sense of gratification.

“There's never been a boundary on Linden Grove. So, we were the first to do it,” she said. “We started off with locating all monumentation we could find. We pulled original deeds for the cemetery and we went out and found everything we could to come back and tell them, ‘This is where your property line lies.’

"The original deed for the cemetery is also very vague. We had to go off of everything that was connected to the cemetery to come up with our boundary."

On top of that, they located hundreds of graves — an impactful experience for Jesse Waggoner.

“It was neat to see how much history was here in Covington," Waggoner said. "I think it's important to document this information, as what we're doing now is setting up the groundwork for an online based system, to where people can go through and find loved ones, and see stones that maybe they don't live nearby."

Waggoner said many of the stones there are sandstone, and the weather has worn them down over time.

“There's going to be quite a few of these graves that we won't be able to make out," he said. "But the hope is that we can make out the people around them, and then slowly work our way into being able to identify some of these unmarked graves."

Cincinnati State is one of the few colleges that offers a four-year surveying degree. Townsend says it’s important work that’s she’s proud of.

"It's very important because of the history aspect,” she said. “There's a lot that went into it. It's basically the framework of how the whole city and how Covington was laid out."

Now, future generations, who will be able to easily look up where their relatives are laid to rest, can thank them.

The remaining half of the cemetery will be surveyed in collaboration with another Cincinnati State class during the upcoming school year.