CHARLOTTE, N.C. (AP) — Jimmie Johnson's alarm clock beeps at 4:30 a.m. His wife and two daughters are still sleeping. So are his fellow NASCAR drivers.

Johnson quietly slips out for a workout, the first of two on a typical day. Two hours later, he's in his kitchen, whipping up breakfast that will be ready when his girls get up for school.

"No chance my competition is getting up this early to put the work in," Johnson said in a text message to The Associated Press that showed the alarm set on his phone. "I will have 35 (cycling) miles in and my kids fed before the first one wakes up."

Johnson likes it that way, too.

Despite a bland reputation he acquired from a workmanlike approach to winning five straight NASCAR titles — and perhaps his affinity for vanilla ice cream — Johnson's commitment to excellence in everything he does makes him not just one of the greatest drivers ever but also one of the most well-rounded and interesting athletes in the world.

Now, the man who paid Snoop Dogg to play at the Las Vegas victory party for his record-tying seventh title has a chance to show the world what is important to him — beyond, of course, winning. Lowe's is leaving the sport after 18 years as the only Cup Series sponsor Johnson has ever had, and his rights are for sale for the first time.

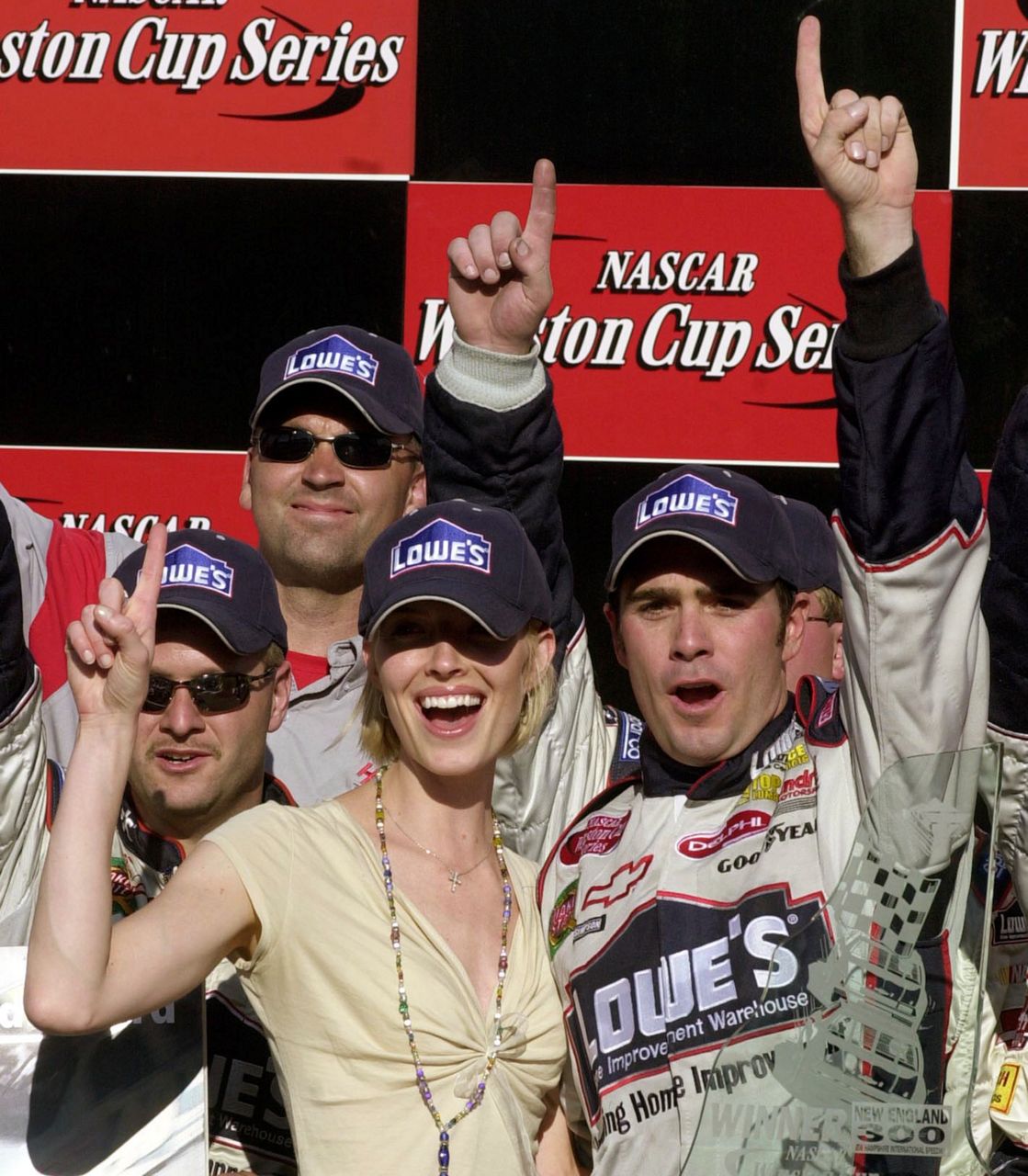

Eighty-three victories in that Lowes-branded No. 48 Chevrolet.

All those titles.

A unique sportsman for Hendrick Motorsports to sell.

And Johnson believes he is more than just a driver looking for a new paint scheme that can be auctioned off to the highest bidder.

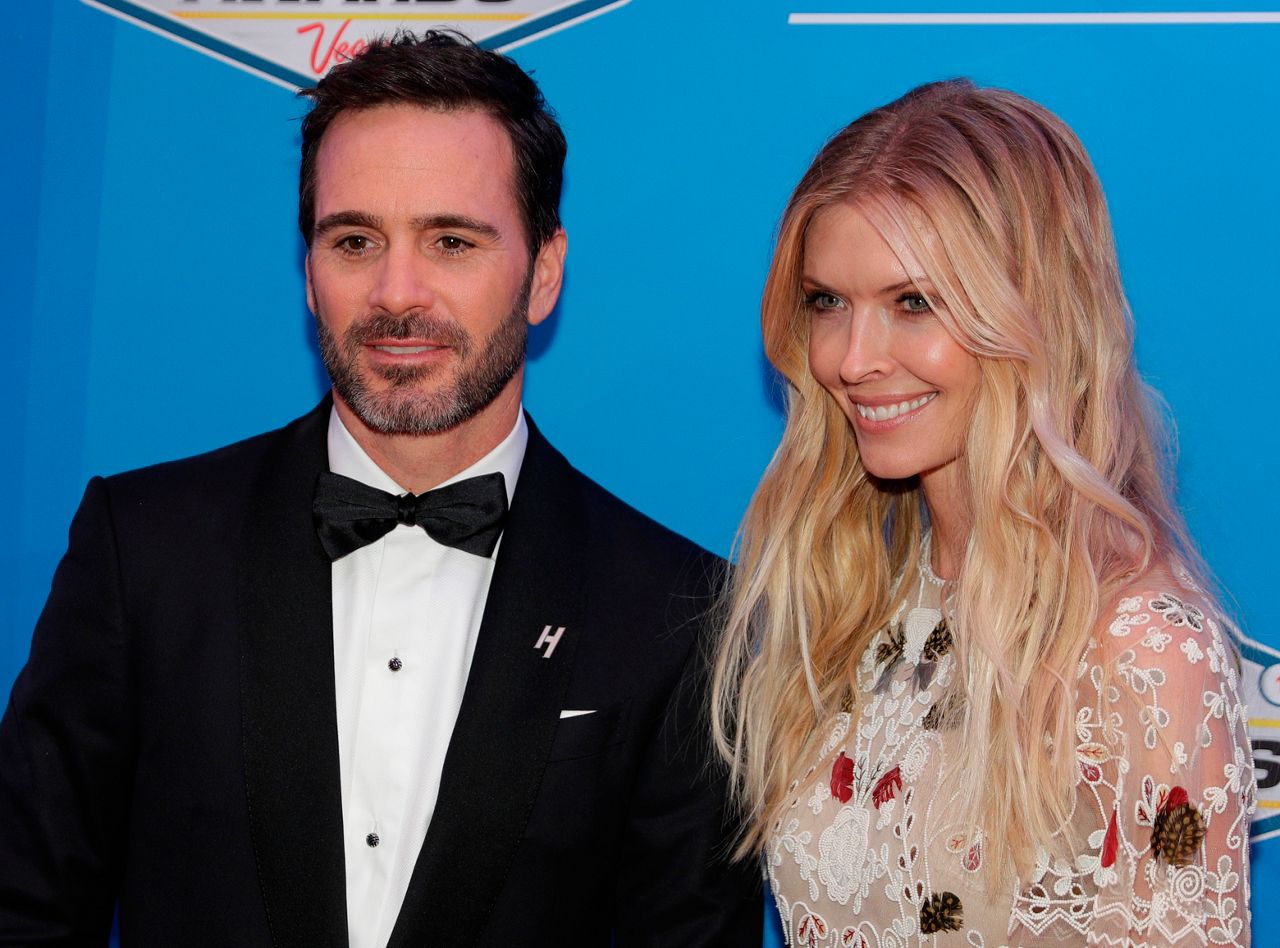

Three weeks after the AP asked for a deeper look into Johnson's sponsorship search, the working father, exercise fiend and leader of Hendrick Motorsports found a spot on his busy schedule. He settled on meeting at SOCO Gallery, his wife's high-end contemporary art space and bookshop located in the trendy Myers Park section of Charlotte.

Arriving just after dropping his youngest daughter off at school, he pulled books off the shelves and pointed to photos he likes, then turned his attention to the art on display. Chandra Johnson booked it well before the artist's popularity soared, and the exhibit was sold out before a single piece was hung at SOCO.

Jimmie Johnson is well-versed in both the artist, a painter named Shara Hughes, and who bought the pieces.

"Only two went to Charlotte collections," he lamented.

Behind the gallery, there is a cross-fit studio with an outdoor exercise space that includes about a half-dozen massive tires hanging from a rope.

"Chani's aesthetic nightmare," Johnson said with a laugh. "She's worked so hard to create this amazing unique space to Charlotte. And now she has to look at that in the backyard."

That Johnson notices such things is part of his evolution from blue-collar kid racing dirt bikes on family outings in his native California to future Hall of Famer. Chandra's influence over their nearly two decades together is also obvious. A former model who was raised in Oklahoma, she was living in New York when they met and they've been together just about his entire time in the top racing circuit in the nation.

At 42, Johnson is still a top driver and adamant that retirement is nowhere on his radar. Yet the statistics and history of NASCAR are clear: The twilight of his career has arrived.

Johnson bought a coffee from the independent nook at the front of the gallery and settled at a small bistro table he'd arranged to be marked as "Reserved."

He pondered the question: What are you selling?

"I think for this seller's market, clearly someone has a golden opportunity to close out with me," Johnson said.

But who?

And, when?

Johnson doesn't have answers as much as a grand plan that could include everything from driving Le Mans and the Rolex 24 at Daytona to triathlons and competitive mountain biking — anything that allows the son of two working parents to chase his desire to win and avoid retirement.

"I know I can't turn off the competition," he said. "I don't think I've ever been more motivated; I don't think I've ever wanted anything more. I want to race and I want to win and I want to do that for a very long time. Me being selfish about what I want to do, the next sponsor transitions with me."

Johnson has matured from the rookie who once led a stair-diving competition at Tony Stewart's birthday party into the most accomplished driver of his generation, matching Hall of Famers Richard Petty and Dale Earnhardt with seven titles. But he runs triathlons, takes team members mountain biking in the woods and will do anything to get a workout in — especially if it's outside.

He is also mired in the longest losing streak of his Cup career: 31 races stretching back almost a year. He turns 43 in September and has two years remaining on his Hendrick contract; there might be another short NASCAR contract after that.

"I've got a handful of years in Cup," he said, leaving himself wiggle room regarding just how many. "If we can find the right sponsor to transition from full-time NASCAR ...

"I mean, I can't stop racing. I'm always going to be racing something," he said. "I'm going to step down from the NASCAR merry-go-round at some point, but I've got a bucket list."

Johnson got to thinking after a chance encounter in January with two-time Formula One champion Fernando Alonso, who is on a quest to race in the top events around the world. Alonso entered the Indianapolis 500 last year, led laps, but failed to finish after his engine blew.

Would Johnson consider running Indy, the race he most admired as a child? He noted Formula One, which recently added plastic halos over the open cockpits in an effort to protect drivers from potentially deadly debris, as an incentive should Indy adopt them.

"I like those halos in Formula One," he said. "Those could get me a little closer to that race."

Johnson has in fact been barred from racing in the Indy 500 by his wife, who thinks the open-wheel racing is too dangerous.

His eldest daughter, 7-year-old Evie, has shown an interest in racing, and Johnson talked to fellow driver Kyle Larson about what she should try. (Johnson wants her in something with a roll cage.) Four-year-old Lydia, with her pink and purple flower-pocked helmet for motorbikes, is a still a wild card.

"Daddy, can you let Danica win today?" she asked him in front of Patrick while on the starting grid of the Daytona 500, which he has won twice.

"I laughed and said to her, 'Daddy wants to win this race, too,'" Johnson said.

The Johnsons' circle of friends includes world-class athletes, artists and celebrities. They ski in Aspen; he even got Dale Earnhardt Jr. to try it. They spend weekends in New York City or Nantucket, where Johnson found himself at Roger Penske's summer home watching the billionaire throw his grandchildren in a pool.

He and Chani have a dream list of European vacations. They appreciate fashion and photography and craft cocktails. They went to Burning Man last year with a group of friends, but you don't see it: They're not the Kardashians.

They also feel a pull toward their community. The Jimmie Johnson Foundation has raised almost $11 million that has been donated to K-12 schools in Charlotte and their respective hometowns in California and Oklahoma.

His impact stretches across the NASCAR garage as scores of drivers and team members go with him on cycling trips, and he has even hired a trainer for some in the industry who needed to lose weight.

As adamant as he is about health and fitness and helping others, Johnson remains firmly committed to himself and pursuit of a record eighth championship.

But he knows what he is up against.

There has been a total rebuild at Hendrick Motorsports after the retirements of Jeff Gordon and Earnhardt, and the firing of Kasey Kahne. Johnson is surrounded by three newcomers and the organization is restructuring operations.

It is a rebuilding period for a storied franchise and it comes at the same time that Chevrolet is rolling out a new Camaro. The car seems to be struggling, but Johnson has backed the work by Chevy and says each of his young teammates — 22-year-old Chase Elliott, 24-year-old Alex Bowman and 20-year-old rookie William Byron — bring valuable feedback to the organization.

All of this has given Johnson a chance to take on a bigger role. Always considered to be the protege of four-time champion Gordon, the team finally belongs solely to Johnson.

"I am enjoying the leadership role I have inside the team," he said. "That's one thing I worked really hard on over the offseason."

Of course, it's easy to lead when he is winning. It's a different story when crew chief Chad Knaus is breathing down his neck and the last checkered flag has been in the rearview mirror for almost a year.

Johnson sought help from former NFL player Leonard Wheeler, who is now a performance coach.

"I'm one that clams up and gets quiet when things get tough, and Chad can make things tough," Johnson said. "I found that the team doesn't need me to be quiet and the team suffers from it, so I've made some huge strides in growth in that department."

A swimmer, diver and water polo player in high school, Johnson realized he did best in a locker-room environment, which doesn't exist in racing. He's learned to recognize what triggers Knaus and come to understand how to confront each issue.

At the end of last season, he said, he was so shut down that he and Knaus were not discussing problems. Crew members began whispering about friction and "it was just toxic," Johnson said.

"I know I am going to flourish and do a better job and be who I need to be in that type of (locker-room) environment, so I am going to create it," Johnson said.

When Johnson first got into NASCAR, he simply showed up at the track and did what Knaus told him. Now he spends hours reading notes, asking Bowman about the simulator, reviewing previous races on YouTube, working on hand-eye coordination drills and jumping in a kart to stay sharp.

After avoiding the gym early in his career, he rises early, gets in two full workouts doesn't stop until he falls into bed 16 hours later. On this day, roughly 12 hours after he first sat down with the AP, he sent that text photo showing the alarm set on his phone for 4:30 a.m. the next day.

A week later, he headed to Bristol Motor Speedway in the hills of Tennessee, riding his bike 100 miles through the mountains to get there.

The next day he slept in.

Until 7 a.m.

"My battery was dead," he texted.

___

More AP auto racing: https://racing.ap.org

___

This story has been corrected to make Bowman's age 24.

Copyright 2018 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.