MOSCOW (AP) — Makhar Vaziev's workday begins before he sets foot inside his office in Moscow's famed Bolshoi Theater.

As he makes his way past the vast columns of the main building, the ballet director pauses to chide a dancer late to class, and then one of his senior coaches, Piotr Nardelli, catches up to him.

The two discuss last-minute details for the Bolshoi's production of Maurice Bejart's "Gaieté Parisienne." The show is in its final rehearsals ahead of its premiere, and there is much to be done.

Vaziev has held the Bolshoi's top creative job since March 2016, when he took over a company reeling from scandal and infighting that tarnished the legacy of his predecessor, Sergei Filin. More than three years later, Vaziev has restored a sense of calm and order to the Bolshoi. As he walks the theater's corridors, he greets dancers, choreographers and other staff on a familiar, first-name basis.

It is clear Vaziev is liked and respected. And he runs a tight ship, keeping tabs on the ballet company and its repertoire.

From his elegantly furnished office, Vaziev can monitor every stage and studio in the Bolshoi with the flick of a remote. A big TV sits in the corner, linked to cameras watching over every space in a kind of ballet master's CCTV. When he's out of the office, he can check the video feeds with a special app on his smartphone.

It is a management style that Vaziev says is vital to maintaining the Bolshoi's stringent standards and ensuring results.

"It's not that I want to control for its own sake," Vaziev told The Associated Press during an exclusive trip backstage at the Bolshoi. Instead, he says, he needs to do it for the performances. "That's why I do this, why I give my time, my experience and my strength. So that we get results onstage."

Vaziev, 58, began his ballet career in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) at the Vaganova Academy, one of the most important schools in the history of ballet. From there, he danced a classical repertoire with the Kirov Ballet at St. Petersburg's famed Mariinsky Theatre, serving as its director from 1995-2008.

He left Russia in 2008 to become ballet director at Italy's La Scala, and over the next eight years worked to revive ballet classics. It was a mission that was well suited for his return to Russia when he joined the Bolshoi. Vaziev believes Russian ballet must stay firmly rooted in what it does best - performing the classics.

But Vaziev insists it's not just about dancing the steps French choreographer Marius Petipa devised for the Bolshoi in the late 19th century. He wants modern dancers, musicians and choreographers to breathe new life into the classics.

"We have a huge global reputation for classical ballet. We don't want to reject that. We'll draw on it, excel at it and grow new generations," Vaziev said. "We need to preserve what's valuable, but we're not a museum. This is a living art form. We need to revive it as we pass it on to new generations."

Outside Vaziev's office, the halls of the Bolshoi buzz with activity. This is the corridor of power, says dancer-turned-teacher Olesya Gradova, where dancers check rigorous rehearsal schedules, find out their parts and see if they get to go on tour.

It's an intense existence, says Gradova, calculating she has spent 80% of her life in the Bolshoi.

"You get very attached to the place, and when people leave, they miss these walls and the people inside them," she said.

Vaziev doesn't sit long at his desk. Most of the day is spent watching his company at work. He drops into a studio where corps de ballet dancers are being put through their paces. Then it's on to a final rehearsal of "Symphony in C," a ballet by George Balanchine.

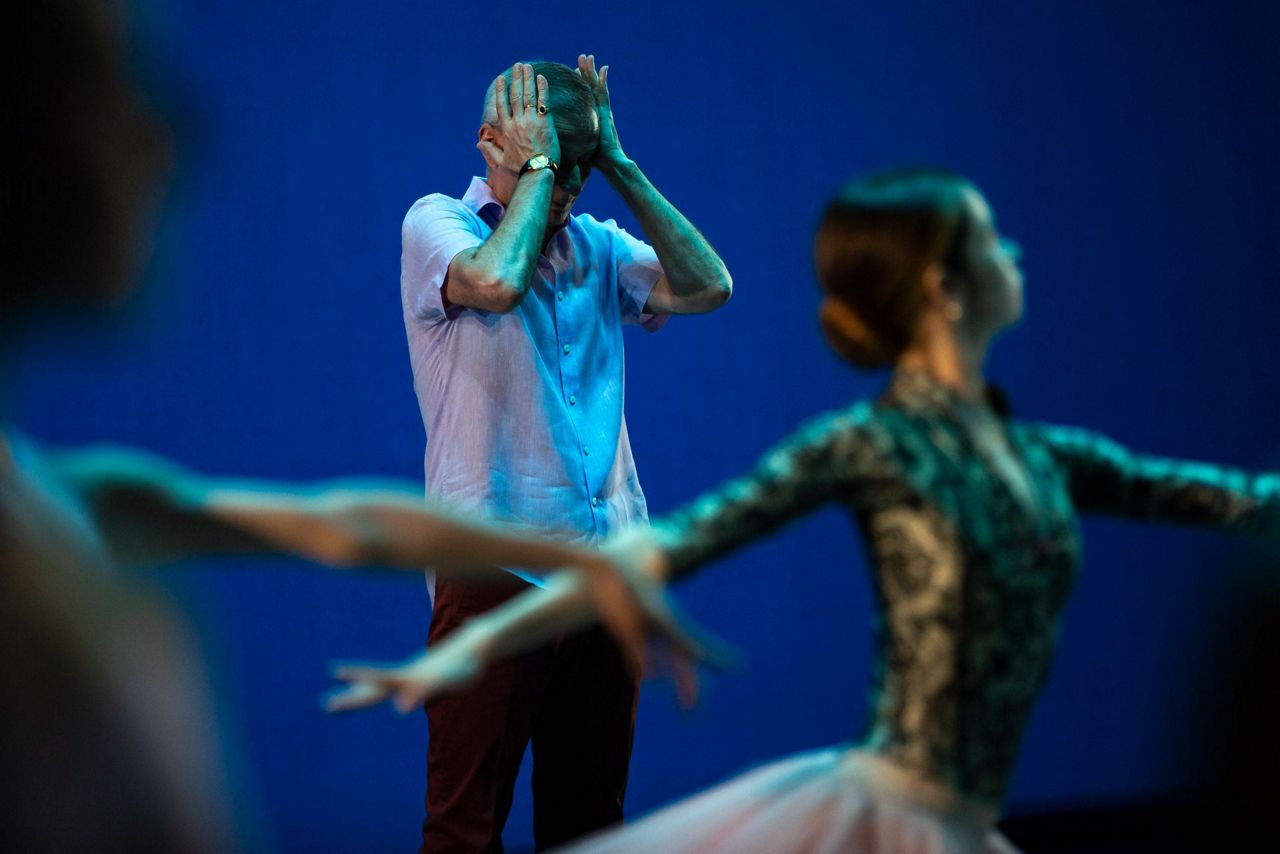

Backstage, the dancers are warming up, chalking their ballet shoes. Some sit checking Instagram, street sportswear over their tutus. Once onstage, Vaziev comes alive — transformed into an exacting ballet master who scrutinizes technique closely and spares no one's feelings if he sees a mistake.

The young dancers seem to take the criticism in their stride.

"Of course, we get tired. We sometimes cry and yell at each other but it's still a joy to be at the Bolshoi," said 24-year-old Ksenia Zhiganshina. "I believe only a tough approach gets results. This is the Russian way."

Most of the Bolshoi troupe comes from Russian ballet schools, which produce dancers renowned for classical discipline and physical strength.

U.S. ballet mistress Elyse Borne rehearses Balanchine's steps with the Bolshoi cast, but it's proving hard for dancers used to the Russian training.

"They make them very strong physically, very strong. It's very strict in style and musicality," Borne said. "It's different to Balanchine and they're struggling with that. It's hard to drill in something different to what they are used to doing."

The dancers are proud to have made it to the Bolshoi, and patriotism plays into their loyalty.

Klim Efimov's parents were Bolshoi dancers. As a child, he remembers watching his mother from the wings. "If you love what you do, then you want to get better, so you work hard," he said.

With a repertoire of 42 productions, two complete corps de ballet and about 220 dancers, the Bolshoi is Russia's premier ballet company. As such, the Kremlin takes a close interest and Russia's political leaders prize conservative values in culture.

Vaziev spends the afternoon at a final run-through of the Bejart ballet "Gaieté Parisienne," whose combination of opera, drama and ballet is groundbreaking for the Bolshoi.

"The only criteria we have is to choose outstanding, talented people who can stage interesting shows. Sometimes it works, sometimes not," he said. "In the theater, it's the way it goes."

___

This story has been corrected to show it has been more than three years since Vaziev took over, not more than four years.

Copyright 2019 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.