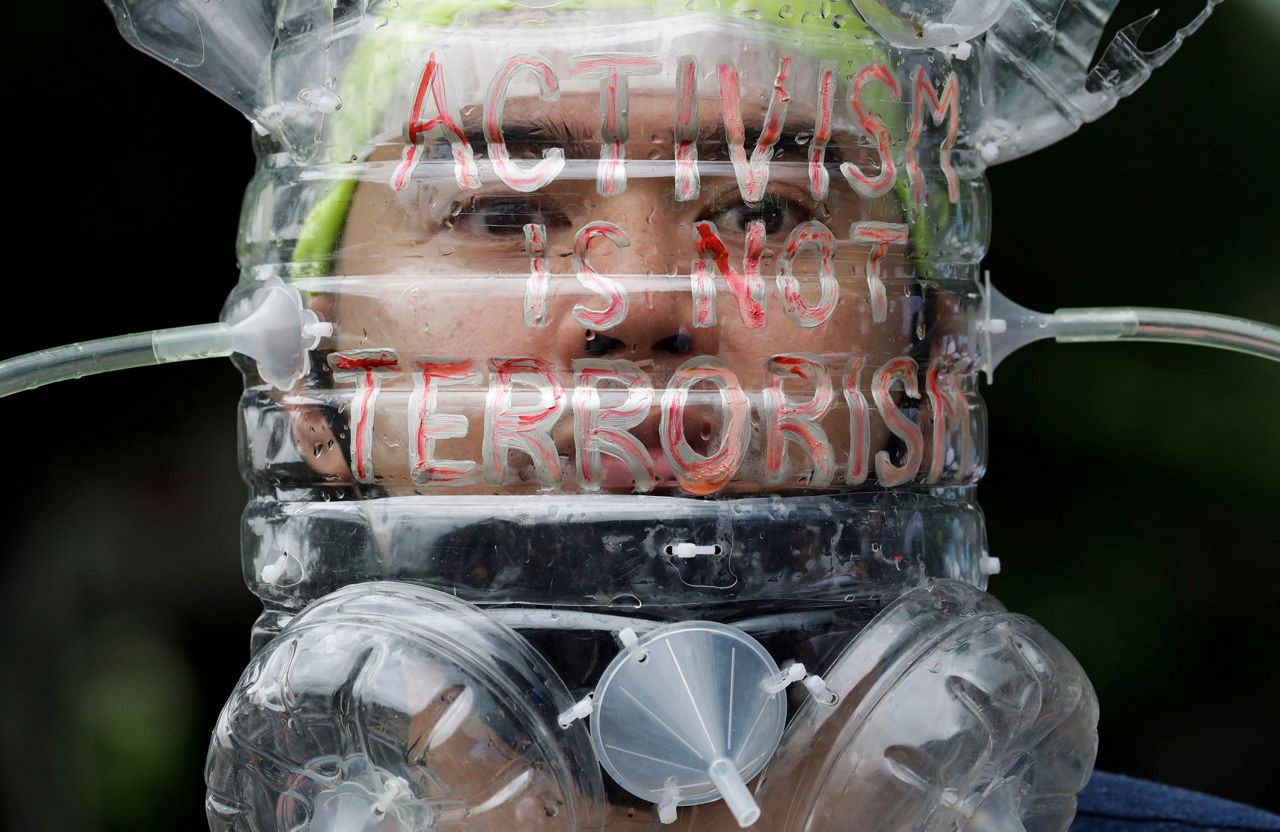

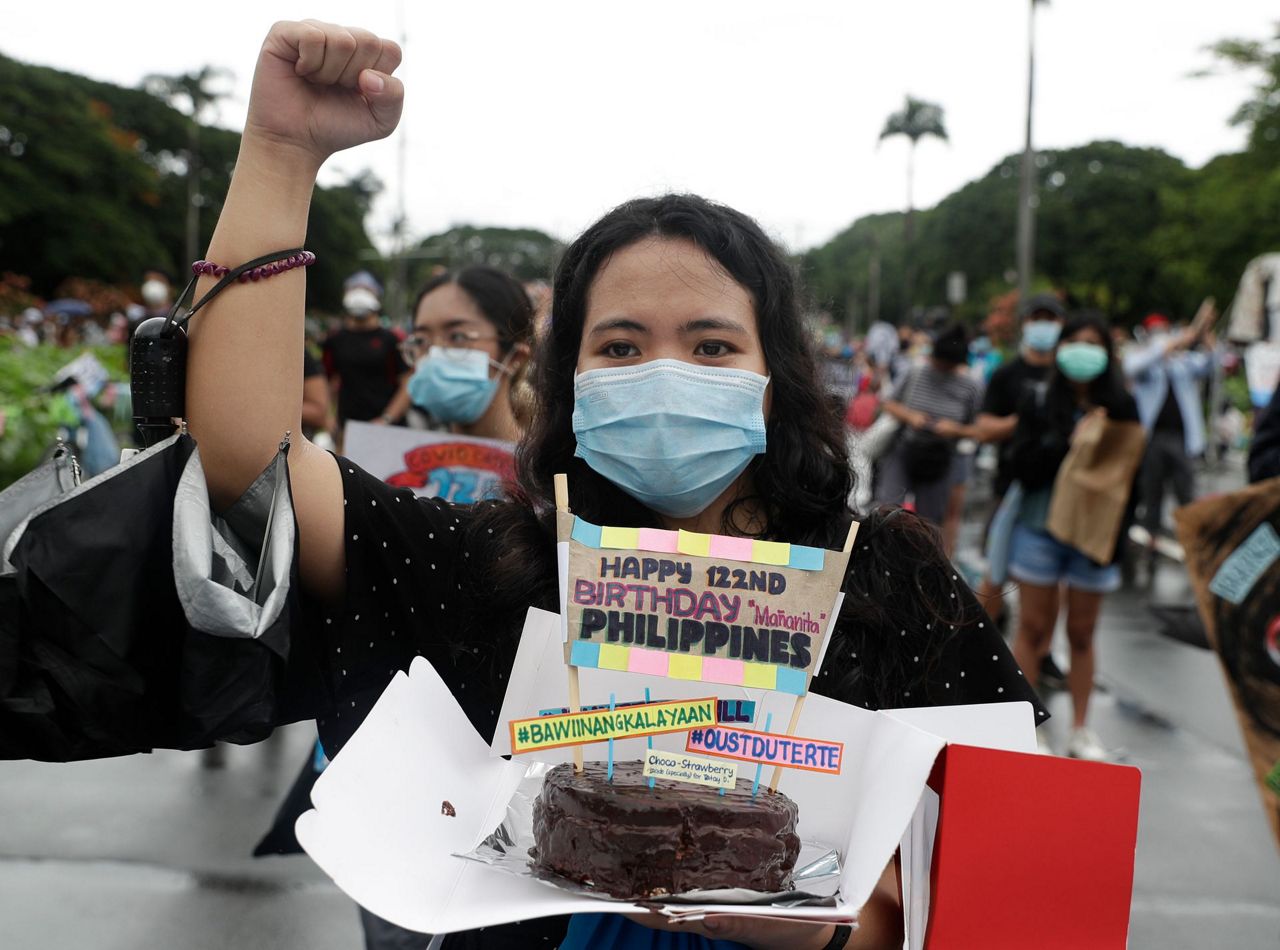

MANILA, Philippines (AP) — Hundreds of activists in the Philippine capital staged protests Friday against a proposed anti-terror law they say could be used to quash dissent, ignoring police threats that they could be arrested for violating coronavirus restrictions against large public gatherings.

The Anti-Terror Act, which Congress has sent to President Rodrigo Duterte to sign into law, allows the detention of suspects for up to 24 days without charge and empowers a government anti-terrorism council to designate suspects or groups as suspected terrorists who could then be subjected to arrests and surveillance.

Military officials have cited the continuing threat of terrorism, including from Abu Sayyaf militants, as reasons the law is needed.

Opponents say the legislation violates the constitution, which restricts detention beyond three days without specific charges, and could be misused to target government critics.

“They should not fool us into believing that this terror bill is for terrorists because it’s meant for all of us who are protesting and dissenting,” said Neri Colmenares, a former member of the House of Representatives who took part in a protest near the University of the Philippines despite police checkpoints set up to prevent massing on the sprawling campus.

The growing opposition to the legislation comes as the Philippine government already faces a chaotic mix of issues linked to the coronavirus pandemic, including a looming recession, record-high unemployment and widespread complaints over delays in the delivery of aid to millions of poor people.

At another protest about 300 workers wearing protective masks carried signs while traveling in a 50-car convoy from a democracy monument to the Commission on Human Rights.

“The government has mishandled everything from the pandemic to the economy,” labor leader Josua Mata said. “Now it’s using health restrictions as a flimsy cover to prevent the people from protesting.”

There were no immediate reports of arrests or violence at the protests, which were held as the Philippines marked its independence from Spanish colonial rule in 1898.

Opposition to the law has been mounting, with Catholic bishops saying the definition of terrorism under the legislation is so broad it could threaten legitimate dissent and civil liberties. The Integrated Bar of the Philippines, the largest group of lawyers in the country, and U.N. rights officials have also expressed concern along with nationalist groups and media watchdogs.

Once signed into law by Duterte, the legislation would replace a 2007 anti-terror law called the Human Security Act that has been rarely used, largely because law enforcers can be fined 500,000 pesos ($9,800) for each day they wrongfully detain a terrorism suspect.

Lawmakers removed such safeguards in the new legislation, which increases the number of days that suspects can be detained without warrants from three to 24.

Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana and other security officials have played down fears the law could be misused, saying the legislation contains adequate penalties for abuse and won’t be used against government opponents.

The proposed legislation states that terrorism excludes “advocacy, protest, dissent, stoppage of work, industrial or mass action and other similar exercises of civil and political rights.”

Military officials back the law.

For years, government troops have been battling Abu Sayyaf militants who have been listed as terrorists by both the United States and the Philippines for ransom kidnappings, beheadings and bombings in the restive south.

In 2017, hundreds of militants affiliated with the Islamic State group laid siege to Marawi city in the south. Troops quelled the siege after five months in a massive offensive that left more than 1,000 people dead, mostly militants, and the mosque-studded city in ruins.

Copyright 2020 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.