BLUEFIELD, W.Va. (AP) — If you’re Christian in Bluefield — and most everyone is, in this small city tucked into the Appalachian Mountains — you have your choice.

You can follow Pastor Doyle Bradford of Father’s House International Church, who has forcefully backed Donald Trump — doubting Trump's defeat in November and joining some congregants at the Jan. 6 “Save America” rally that degenerated into the Capitol riot.

Or you can go less than 3 miles away next to the rail yard, to Faith Center Church, where Pastor Frederick Brown regards Bradford as a brother — but says he's seriously mistaken. Or you can venture up East River Mountain to Crossroads Church, where Pastor Travis Lowe eschews Bradford’s fiery political rhetoric, seeking paths to Christian unity.

The three churches have much in common. All of them condemn the desecration of the Capitol and pray for a way to find common ground.

But they diverge on a central issue: What is the role of evangelical Christianity in America’s divisive politics?

Bradford and his flock defend his actions as expressions of freedom of speech and religious freedom, and say they should be allowed to voice their views against what they feel is an assault on democracy and Christian values. But his fellow pastors fear that fiery rhetoric and baseless claims made online and from the pulpit could stoke more tensions, rancor and divisiveness.

Though AP VoteCast found that about 8 in 10 evangelical voters supported Donald Trump in November — and though broadly, they have backed the political efforts of church leaders — they are not monolithic.

As is evident in this Appalachian town of just more than 10,000.

___

Long before he followed his pastoral calling, Doyle Bradford dug for coal underground — a traditional vocation in Bluefield, where folks proudly recall how rock extracted from the surrounding hills powered ships in the two world wars and helped build the skylines of cities across America.

Joe Biden carried parts of Bluefield itself, small splotches of blue in the sea of red that is West Virginia. But Mercer County gave more than three-quarters of its votes to Trump, and Bradford and his pronouncements are very much in line with that.

“For those of you who are surprised at my attending (the Washington rally), we have 2 choices,” he wrote on Facebook, “I stand with the platform that most closely aligns with my faith and values. Those do not include the murder of babies in the womb, and not knowing which bathroom one should use and banning pronouns.”

He said he did not participate in or even see the violence Jan. 6. On Facebook, he said he believed it was a “planned response from non Trump supporters.” He claimed there was “plenty of evidence of fraud” in the presidential election — though there is no evidence that that is the case — and called on people to “wake up” because “America is at stake.”

In an interview, Bradford fiercely defended his actions and denied he was part of a larger movement toward Christian nationalism, described by a coalition gathered by the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty as an ideology that “demands Christianity be privileged by the state and implies that to be a good American, one must be Christian.”

“I consider myself a Christian who loves America, but what we’ve got going on in the Earth today is, if a Christian does love America, they’re automatically called nationalist,” Bradford said.

“I do not believe that America is any greater in the eyes of God than any other country. But as a minister of the Gospel, I do not want to be shut out of the public arena. I do have freedom of speech and freedom of religion, and it is my personal belief that America is going in a direction that will cause great harm to America.”

At Faith Center Church, Frederick Brown does not deny Bradford’s right to speak, but he does question the wisdom and even the godliness of some of the things he’s said.

Brown wants other religious leaders to return to “real Christianity” instead of getting wrapped up in the political arena. Although he respects Bradford as a “tremendous teacher” who loves God, he criticized some of his comments.

“With all love and due respect to my brother, I just feel that he has been completely out of order. I believe that he has said things publicly that just were not biblical,” he said.

“I’ve watched him declare that the wrath of God was coming upon people that did not vote for Trump, and the wrath of God was coming on the people that rigged the election. All of these things, from my perspective, that is totally contrary to what we teach and what we preach in Christendom.”

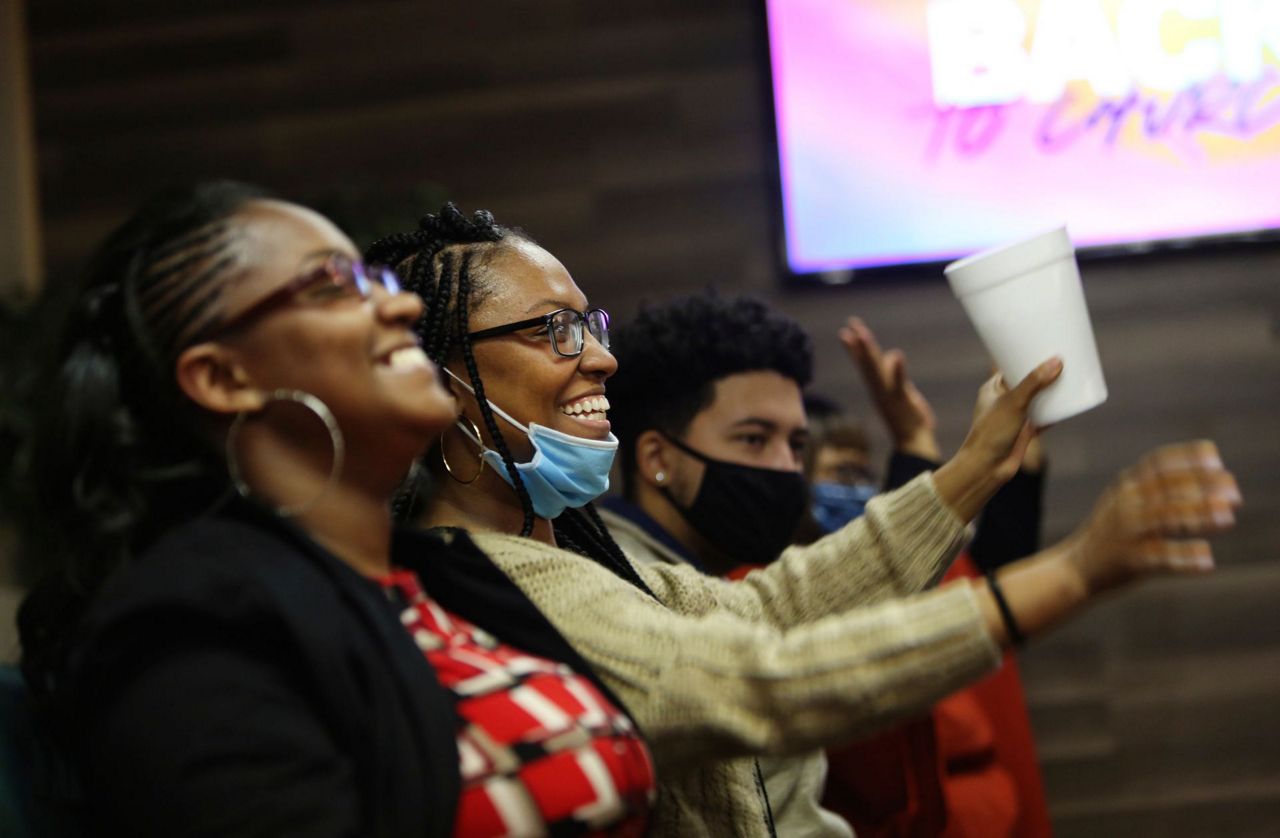

During a recent Sunday service — the first in-person one since November, due to the pandemic — Brown thanked the mostly Black congregation for its support after he contracted the coronavirus along with his wife and 17-month-old twins. Then he asked them to put politics aside and trust God.

“I don’t know about you all,” he said, “but I’ve been through 11 presidents, and I have survived them all.”

In a town where another church marquee read, “Don’t look to the White House. Look to heaven,” Brown’s message reverberated.

“I’m ready for this political jockeying to be over with,” said congregant Jonathan Jessup. “You know, I’m sick of it because the only thing it’s doing is causing more division.”

At Crossroads Church, Travis Lowe has struggled with his own inclination to preserve Christian unity at all costs. He supported Black Lives Matter protests, but was reproached by a friend because his comments were divisive. He resolved to rein in his political speech.

In a post on Medium, he recounted how he struggled to remain silent as “pastors and prophets began to publicly take sides in the U.S. election. I was silent as scriptures were used to demonize political enemies. I was silent as the language of violence flowed from the mouths of `people of peace.’”

He recalled Bradford posted on Facebook after the first presidential debate that leaders in the church had supported Trump for years for not being a politician but were now backpedaling because he was not acting like one: “If you said he was the leader God chose, own it."

After Jan. 6, Lowe finally spoke out: “I can no longer risk having blood on my hands for the sake of unity.”

“I struggle to see the way that people can wave a banner of Christianity and still employ the language of violence, and even a lot of the imagery that I’ve seen used will reference Jesus as being a lion, a lion of the tribe of Judah,” he said. “But one of the things that I recognize in the New Testament is that every time that we expect Jesus to show up as a lion, he shows up as a lamb.”

___

Bradford takes pride in the diversity of his congregation, which includes white, Black and Latino members. His flock defend their pastor and say his church has transformed their lives through acceptance and love.

That does not mean that they are happy with the violence they saw in Washington on Jan. 6, or that they are all certain that their faith offers clear instruction on how they should act politically.

“My biggest prayer is just that, God, that we would see the truth ... and that this country would come together in unity,” said 21-year-old Kara Sandy, a congregant and junior at Bluefield State College.

Congregant Brenda Gross teared up when she was asked about Jacob Chansley, an Arizona man who was part of the insurrection at the Capitol. Known as the “QAnon Shaman,” Chansley led a prayer at the Senate chamber thanking God “for allowing the United States of America to be reborn,” while shirtless and wearing face paint and a furry hat with horns.

“I don’t know what prayer he prayed, but our Jesus was meek and mild. ... He wasn’t representing the Jesus that I know and love,” she said.

Her husband attended the Washington rally with Bradford. Gross said she both stands by her pastor and prays for Biden, though she worries about Biden’s support for abortion rights, and how her community might lose jobs if he limits the use of coal.

Gina Brooks, who leads the children’s ministry at Bradford’s church, agreed that the Capitol melee was a sorry spectacle: “It’s sad, it’s really disheartening to see people take on the name Christian and they’re not.”

Brooks said she voted for Trump because she’s pro-life, but was often outraged by his behavior and felt it clashed with her Christian values.

Her 18-year-old son Jacob, who is studying music at Bluefield College, a private, Christian liberal arts college, said that at times it’s best to try to remain impartial.

“It’s important that people like us realize that we shouldn’t take sides, because the sides are what’s basically dividing the country,” he said. “As the body of Christ, our duty is to realize that this is sort of, I don’t know if I want to say like above us, but above our understanding. So, I think it’s just important that we just seek answers from our creator.”

But his mother said politics and religion are often deeply intertwined. She backed the decision to demonstrate by her pastor, whose most recent Facebook posts have been less strident, focusing on a message of unity and humility.

“I agree with him ... was there things that were wrong in our election? Absolutely. Is it our responsibility to intercede for this nation? Absolutely,” she said.

“The end result is what the Lord’s will is, and if the Lord’s will is this, then so be it. But it doesn’t mean that we stop interceding in the spirit.”

___

Associated Press writer Elana Schor in Washington contributed to this report.

___

Associated Press religion coverage receives support from the Lilly Endowment through The Conversation U.S. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

Copyright 2021 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.