JOSHIMATH, India (AP) — As hundreds of rescue workers scoured muck-filled ravines and valleys on Tuesday looking for survivors after the sudden collapse of a Himalayan glacier, distraught relatives gathered at the disaster site to search for family members, almost resigned to the likelihood they were dead.

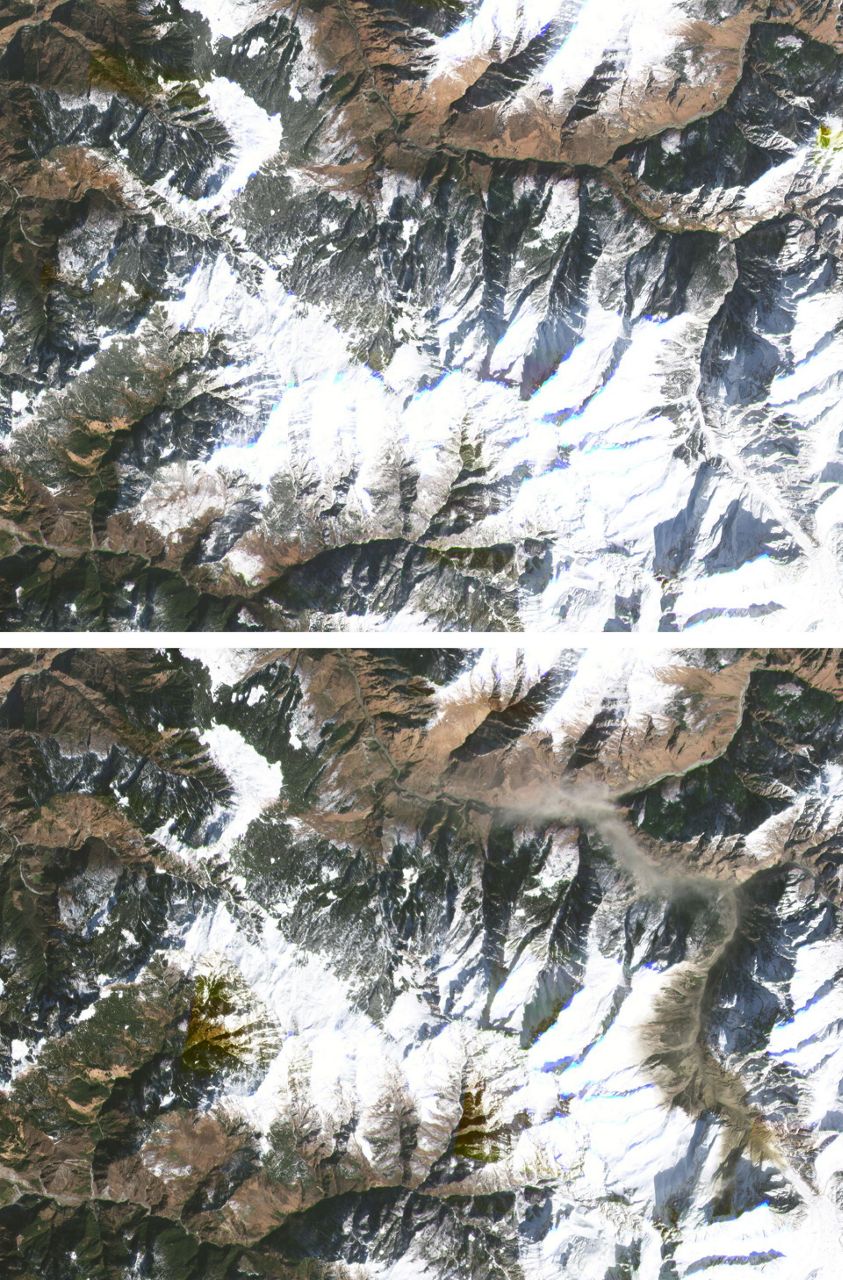

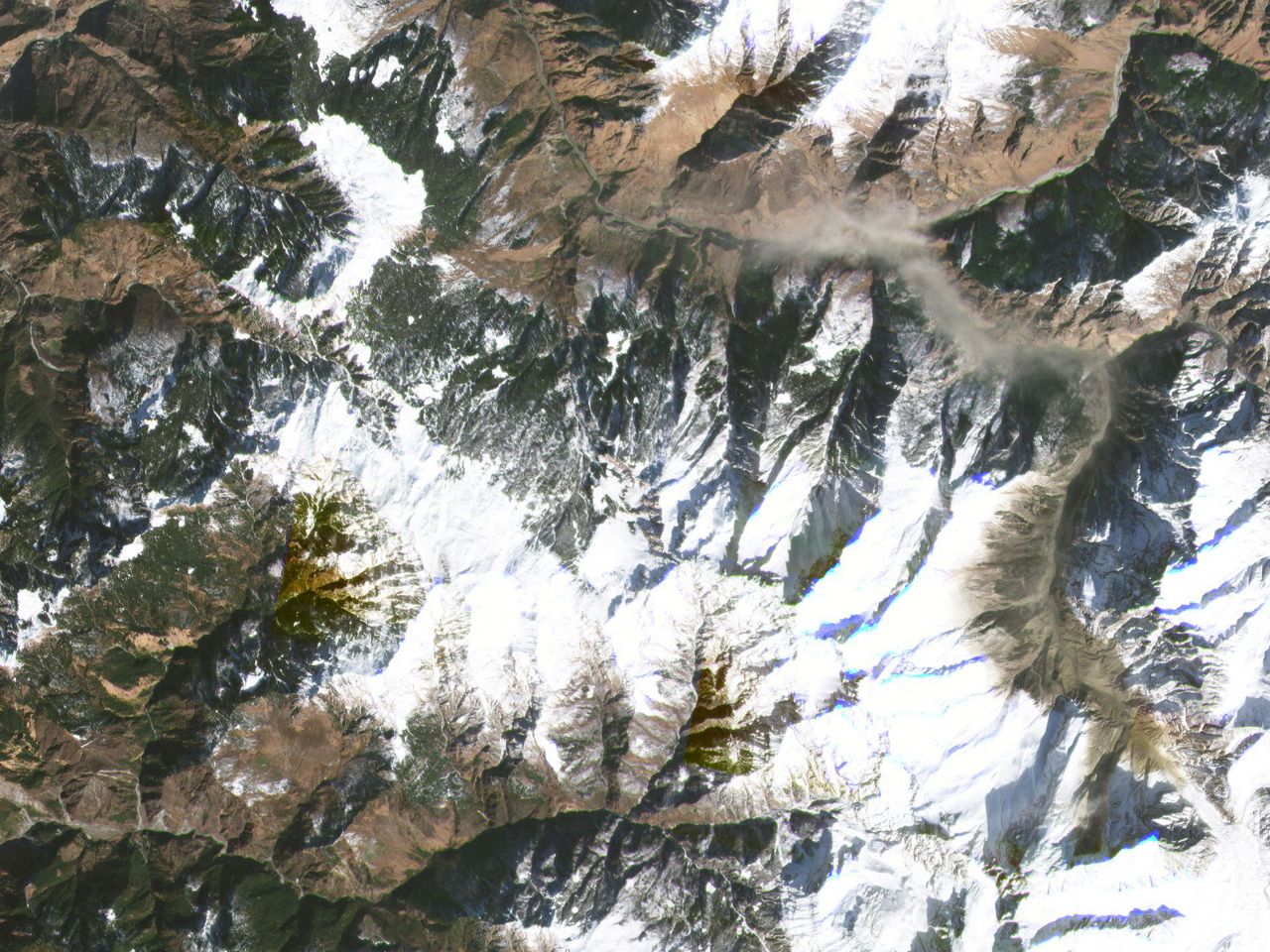

The disaster was set off when part of a glacier near Nanda Devi mountain broke off Sunday morning, unleashing a devastating flood that left at least 32 people dead and 165 missing.

Scientists are investigating what caused the glacier to break — possibly an avalanche or a release of accumulated water. Experts say climate change may be to blame since warming temperatures are shrinking glaciers and making them unstable worldwide.

The floodwater, mud and boulders roared down the mountain along the Alaknanda and Dhauliganga rivers, breaking dams, sweeping away bridges and forcing the evacuation of many villages while turning the countryside into what looked like an ash-colored moonscape.

It swept away a small hydroelectric project and damaged a bigger one downstream on the Dhauliganga. Flowing out of the Himalayan mountains, the two rivers meet before merging with the Ganges River.

One of the major rescue efforts is focused on a tunnel at a hydroelectric power plant where more than three dozen workers have been out of contact since the flood. Rescuers used excavators and shovels to clear sludge from the tunnel in an attempt to reach the workers as hopes for their survival faded.

In the distance, some families tried to identify their loved ones and grieved for the dead.

No one has been rescued from the tunnel since Sunday, with chances for a miracle declining with each passing moment. It could still take days or weeks before many bodies are found.

“There is nothing left here,” said Rani Devi, who wandered around the disaster site searching for her husband three days after the wall of water from the collapsed glacier barreled down the Alaknanda and swept away the hydroelectric power plant he was working at.

Devi, 48, traveled almost 700 kilometers (435 miles) from neighboring Himachal Pradesh state after hearing about the tragedy on TV news channels. On Tuesday, she walked through the reddish-brown mud, from one government official to another, hoping for any news about her husband. There was none.

"I don’t know how will I go back home. What will I even tell my family?” she said, holding back tears.

Most of the missing were people working on the two projects, part of many plants the government has been building on several rivers and their tributaries in the mountains of Uttarakhand state.

Rescuers said it was difficult to predict how long it would take to open the tunnel because of the heavy mud inside, but that they hoped to find people still alive.

“It’s a very big challenge, but we are trying our best and with full strength,” said Aditya Pratap Singh, deputy commandant of the National Disaster Response Force.

The power of the roaring wall of water was first noticed by residents of multiple villages perched on the valley slopes.

Rajeev Semwal heard a sound similar to rumbling clouds and then watched the usually blue waters of the Alaknanda turn muddy.

“I understood disaster had indeed struck,” said Semwal, a resident of Tapovan village in Uttarakhand state where the power plant is located.

Semwal’s brother-in-law and younger brother both worked at the power plant. His younger brother was inside the tunnel that was flooded and has not been heard from since.

Home Minister Amit Shah told Parliament that rescue efforts were on a “war footing.” He said there was no danger of flooding in low-lying areas of the region.

The ecologically sensitive Himalayan region is prone to flash floods and landslides.

More than 6,000 people are believed to have been killed in floods in 2013 which were triggered by the heaviest monsoon rains in decades.

___

Saaliq reported from New Delhi.

Copyright 2021 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.