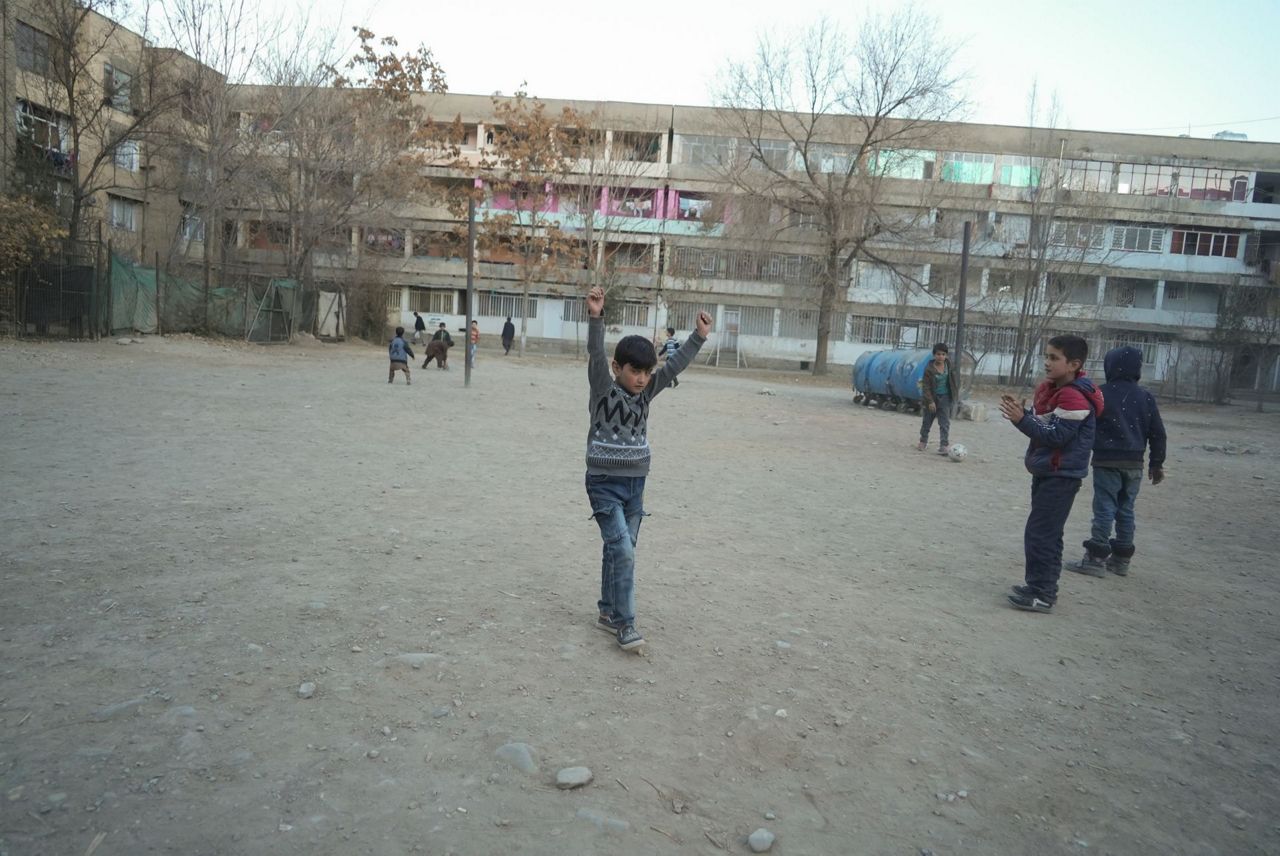

KABUL, Afghanistan (AP) — In a Kabul neighborhood, a gaggle of boys kick a yellow ball around a dusty playground, their boisterous cries echoing off the surrounding apartment buildings.

Dressed in sweaters and jeans or the traditional Afghan male clothing of baggy pants and long shirt, none stand out as they jostle to score a goal. But unbeknown to them, one is different from the others.

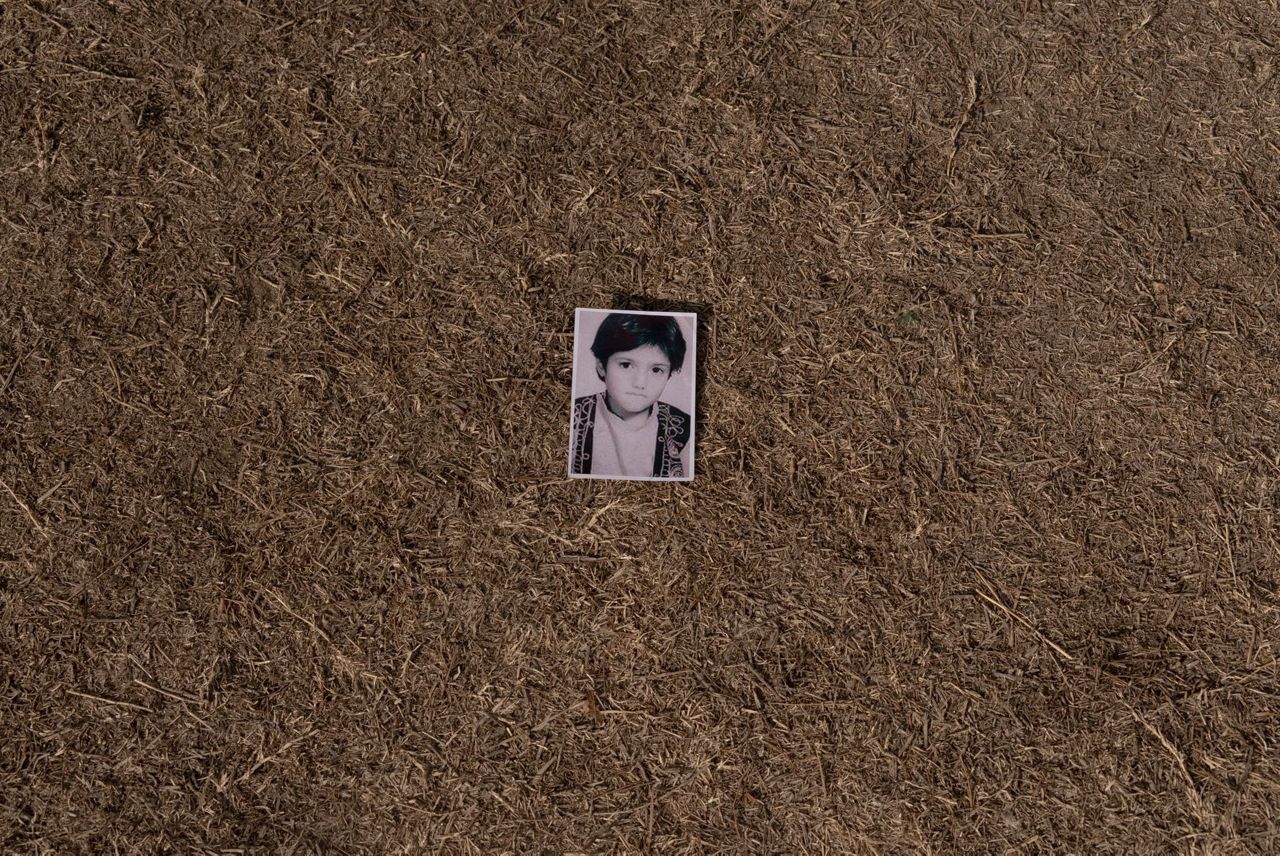

At not quite 8 years old, Sanam is a bacha posh: a girl living as a boy. One day a few months ago, the girl with rosy cheeks and an impish smile had her dark hair cut short, donned boys' clothes and took on a boy’s name, Omid. The move opened up a boy's world: playing soccer and cricket with boys, wrestling with the neighborhood butcher's son, working to help the family make ends meet.

In Afghanistan’s heavily patriarchal, male-dominated society, where women and girls are usually relegated to the home, bacha posh, Dari for “dressed as a boy,” is the one tradition allowing girls access to the freer male world.

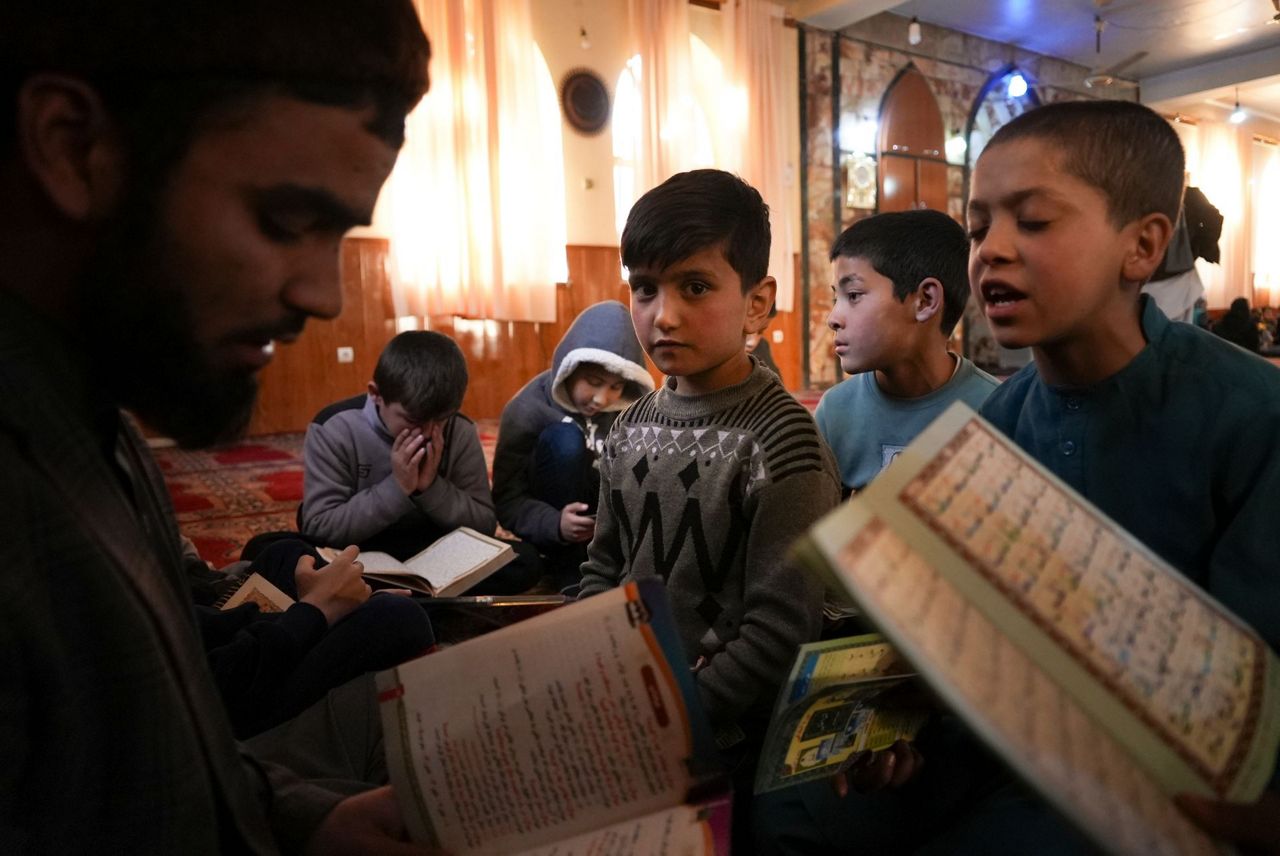

Under the practice, a girl dresses, behaves and is treated as a boy, with all the freedoms and obligations that entails. The child can play sports, attend a madrassa, or religious school, and, sometimes crucially for the family, work. But there is a time limit: Once a bacha posh reaches puberty, she is expected to revert to traditional girls’ gender roles. The transition is not always easy.

It is unclear how the practice is viewed by Afghanistan’s new rulers, the Taliban, who seized power in mid-August and have made no public statements on the issue.

Their rule so far has been less draconian than the last time they were in power in the 1990s, but women’s freedoms have still been severely curtailed. Thousands of women have been barred from working, and girls beyond primary school age have not been able to return to public schools in most places.

With a crackdown on women’s rights, the bacha posh tradition could become even more attractive for some families. And as the practice is temporary, with the children eventually reverting to female roles, the Taliban might not deal with the issue at all, said Thomas Barfield, a professor of anthropology at Boston University who has written several books on Afghanistan.

“Because it’s inside the family and because it’s not a permanent status, the Taliban may stay out (of it),” Barfield said.

It is unclear where the practice originated or how old it is, and it is impossible to know how widespread it might be. A somewhat similar tradition exists in Albania, another deeply patriarchal society, although it is limited to adults. Under Albania’s “sworn virgin” tradition, a woman would take an oath of celibacy and declare herself a man, after which she could inherit property, work and sit on a village council — all of which would have been out of bounds for a woman.

In Afghanistan, the bacha posh tradition is “one of the most under-investigated” topics in terms of gender issues, said Barfield, who spent about two years in the 1970s living with an Afghan nomad family that included a bacha posh. “Precisely because the girls revert back to the female role, they marry, it kind of disappears.”

Girls chosen as bacha posh usually are the more boisterous, self-assured daughters. “The role fits so well that sometimes even outside the family, people are not aware that it exists,” he said.

“It’s almost so invisible that it’s one of the few gender issues that doesn’t show up as a political or social question,” Barfield noted.

The reasons parents might want a bacha posh vary. With sons traditionally valued more than daughters, the practice usually occurs in families without a boy. Some consider it a status symbol, and some believe it will bring good luck for the next child to be born a boy.

But for others, like Sanam’s family, the choice was one of necessity. Last year, with Afghanistan’s economy collapsing, construction work dried up. Sanam’s father, already suffering from a back injury, lost his job as a plumber. He turned to selling coronavirus masks on the streets, making the equivalent of $1-$2 per day. But he needed a helper.

The family has four daughters and one son, but their 11-year-old boy doesn’t have full use of his hands following an injury. So the parents said they decided to make Sanam a bacha posh.

“We had to do this because of poverty,” said Sanam’s mother, Fahima. “We don’t have a son to work for us, and her father doesn’t have anyone to help him. So I will consider her my son until she becomes a teenager.”

Still, Fahima refers to Sanam as “my daughter." In their native Dari language, the pronouns are not an issue since one pronoun is used for “he" and “she.”

Sanam says she prefers living as a boy.

“It’s better to be a boy ... I wear (Afghan male clothes), jeans and jackets, and go with my father and work,” she said. She likes playing in the park with her brother’s friends and playing cricket and soccer.

Once she grows up, Sanam said, she wants to be either a doctor, a commander or a soldier, or work with her father. And she’ll go back to being a girl.

“When I grow up, I will let my hair grow and will wear girl’s clothes,” she said.

The transition isn’t always easy.

“When I put on girls’ clothes, I thought I was in prison,” said Najieh, who grew up as a bacha posh, although she would attend school as a girl. One of seven sisters, her boy’s name was Assadollah.

Now 34, married and with four children of her own, she weeps for the freedom of the male world she has lost.

“In Afghanistan, boys are more valuable,” she said. “There is no oppression for them, and no limits. But being a girl is different. She gets forced to get married at a young age.”

Young women can’t leave the house or allow strangers to see their face, Najieh said. And after the Taliban takeover, she lost her job as a schoolteacher because she had been teaching boys.

“Being a man is better than being a woman,” she said, wiping tears from her eye. “It is very hard for me. ... If I were a man, I could be a teacher in a school.”

“I wish I could be a man, not a woman. To stop this suffering.”

Copyright 2022 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.