POLK COUNTY, Fla. — COVID-19 will have a long-standing impact on farmers across Florida but as I dived into the lives of these cultivators, I learned they are fighting two invisible beasts: The virus and severe weather.

“The water flooded the entire area; killed off all the younger crops that were coming up,” explained Millie of Davie Florida.

In the heart of The Gold Coast, tucked behind a windy road and a long dirt path, you will find dozens of migrant Jamaican farmers tirelessly working to reclaim their land after Hurricane ETA wiped them out.

What You Need To Know

- Covid-19 impacts on black farmers

- Many say they have had to deal with many obstacles in 2020

- A closer look at farmers across Florida

“We’ve experienced hurricane’s before but not like this,” said another south Florida farmer. “Sometimes I sleep on the farm at night because I’m too tired to drive the hours it takes to get home; this is my only source of income.”

This is the situation for many farmers whose lifeline is connected to their crops. When the pandemic shut down hotel and restaurant industries agriculturalist reported losses of 39%-46%, according to the Florida Farm Bureau. Though shellfish farmers reported losses up to 80%.

Migrant farmers work to reclaim land after severe weather destroyed more than half their crops. Hear their stories on @BN9 pic.twitter.com/oPAKefxQT3

— Ashonti Ford TV (@AshontiFordBN9) December 9, 2020

“I’m a 3rd generation on one side and a 4th generation on the other, growing up there was nothing else I’d rather do,” said Therus Brown of Brooksville. “If there is a young man or woman out there that wants to farm, I want them to know that there is still a man out there riding his tractor.

Brown said that farming dates back decades in his family and even further back in his culture; it’s a way of life. This is a common story for many central Florida farmers, including Thomas Nichols in Ocala. He’s been farming for over 40 years.

“It’s not like it was back in the day; a young farmer needs more help today – this tractor here cost over $20,000 alone,” explained Nichols.

At one point, Nichols was leasing over 800 acres of land throughout Florida. Just recently the owners told Nichols they planned to build homes on more than 60% of that land.

FRESH COCONUT WATER 🗣@CoconutCart walks 5 miles in the sand with over 50lbs of coconuts everyday. Hear how his lifeline is connected to Florida crops on @BN9 pic.twitter.com/FQMvIVZXea

— Ashonti Ford TV (@AshontiFordBN9) December 8, 2020

“I’ve seen a lot of building here in central Florida, I also have some land in South Florida too,” said Nichols.

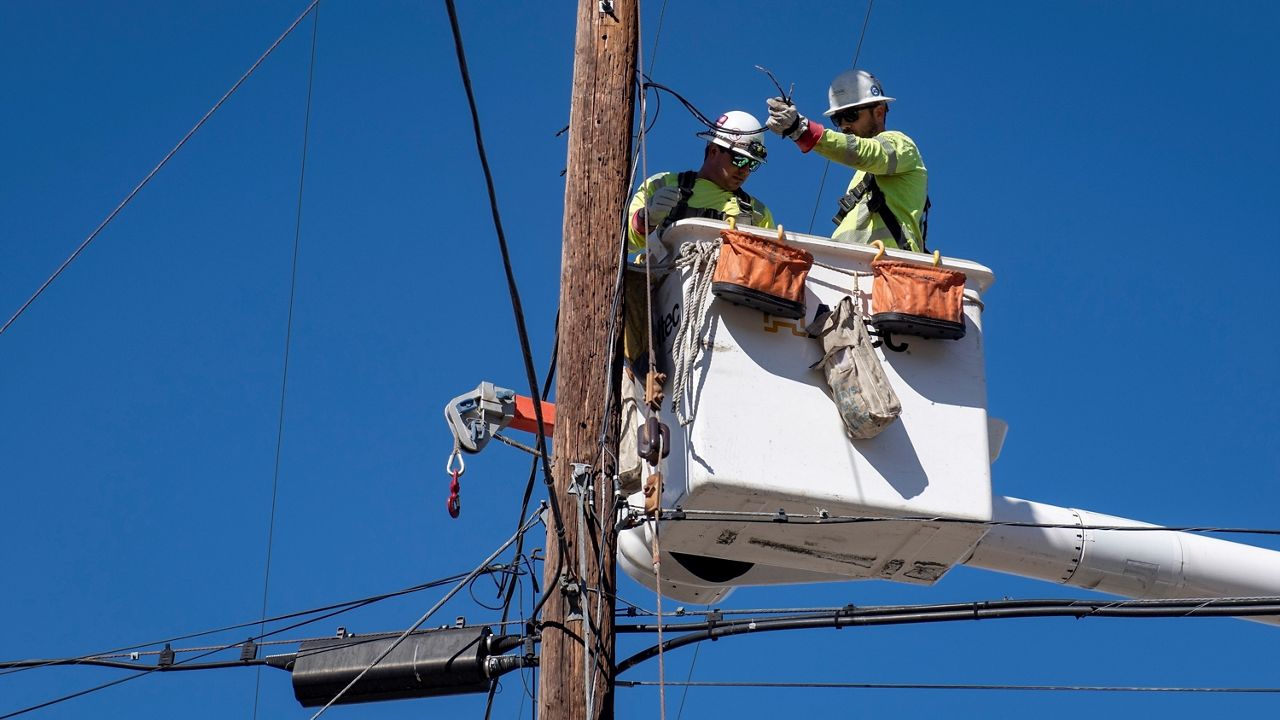

Road construction projects ate away at Nichols production more than COVID-19 but in Lake Placid, 81-year-old Calvin Bryant told me he is fighting a different battle.

“I think at one time, we had to depend on each other to survive,” said Bryant.

Bryant is originally from Valdosta, Georgia. This is where he learned how to farm.

“I didn’t go to school when I was younger, like they do now – I worked on the farm, explained Bryant.

Bryant has since gone back to Valdosta to buy the land he grew up on. He now produces food in both Florida and Georgia.

“This here land we’re standing on is full of okra, turnip, mustard greens, tomatoes and broccoli,” he said. “If people don’t have money, I mainly just give it away – the more I give the more God keeps replacing; that’s the way of life.”

Since the pandemic, Bryant told me that he picks food from his garden to give away to the community.

Orlando farmer handpicks garden 🪴 produce after his father passes away from illness. Hear more central farmer stories on @BN9 @MyNews13 pic.twitter.com/QC4Gq5N9Mh

— Ashonti Ford TV (@AshontiFordBN9) December 11, 2020

“I want to show people that we need more producers, not consumers – that’s the way the world should be; more people creating food for themselves,” said Bryant.

Though in this current period of time, producing hasn’t been the largest issue – it’s the lack of demand. COVID-19 shocked our supply and demand system leaving farmers with more produce than they can sell.

The USDA reports that the volume of delinquent farm real estate and non-real estate loans increased 17%, compared to the prior year. Texas agriculture alone reported upwards of $8 billion in losses.

Though many farmers are still finding reasons to smile. Ray Warthen in Orlando has three different farms, each located in food deserts. Spectrum Bay News 9 took a trip to his newest farm located in the heart of downtown Orlando.

“It’s important to my wife and I that these underserved communities have healthy options; many of them just don’t know where to find it,” said Warthen.

Mt. Zion Farms can be found throughout central Florida however this particular farm is unique in the location and the purpose. Warthen uses music to draw the surrounding community in.

“They call me The Black Mamba Farmer,” said Warthen.

Much like many of our Florida farmers, Warthen uses his super power to continue pumping roots of healthy eating into his community.

The work done on the South Florida Farms is supported by the Pulitzer Center.